Spectrum Road — electric guitarist Vernon Reid, bassist Jack Bruce, keyboardist John Medeski and drummer Cindy Blackman — playing high energy, high volume music at the Blue Note (NYC) this weekend inspired by the jazz-rock amalgam the late, great Tony Williams created 40 years ago, seems utterly cutting edge. Or is it just my old ears, getting deaf to quieter subtleties?

Opening night the quartet was over-the-top exciting, as Reid’s fast-fingering of long and urgent phrases, Bruce’s unfalteringly creative and propulsive bottom lines (he’s the guy who kept Cream’s long jams like the 16-minute “Spoonful” from bogging down), Medeski’s swirling, splashing organ-and-synth physicality and Blackman’s ferocious full-on attack cohered into a huge sound with a single intent: improv intense enough for headbangers, bluesy but harmonically exploratory enough to satisfy avant-jazzers.

Experiments in crossover were already occuring then. Among those leading the charge: flutist Jeremy Steig and his Satyrs; the Free Spirits with guitarist Larry Coryell, saxophonist Jim Pepper and drummer Bob Moses; the Blues Project; Paul Butterfield’s Blues Band; Blood, Sweat and Tears under the direction of Al Kooper, and Miles Davis, Tony Williams’ boss (Frank Zappa and Jimi Hendrix, too). Miles had not yet had his breakthrough with Bitches Brew — in fact, Williams left the trumpeter, who’d been his mentor, before then, because Davis had cast guitarist John McLaughlin, whom Williams had brought from England to be in Lifetime, for In A Silent Way. As if Miles could steal Williams’ thunder!

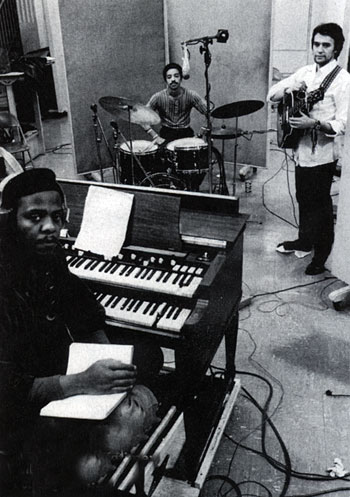

from left – Larry Young, Tony Williams, John McLaughlin. promotional photo – no copyright infringement intended

Turn It Over (Jack Bruce joining to make Lifetime a quartet) and Ego (different personnel), before getting swamped by who-knows-what for Lifetime’s least successful outing, The Old Bum’s Rush. None of these records were admired by the old-guard jazz fans of the early ’70s who mostly ruled the critical roost, but that didn’t stop Williams’ cohort — kids 25 and younger, who were open to psychedelia as well as jazz, from eating them up. Lifetime rocked. Oh yeah — Williams took a lot of heat for his wimpy vocals, but as sung by Bruce (“There Comes a Time”) especially, and Blackman (“Where”), the lyrics and songs are just fine.

bie Hancock and Wayne Shorter make for fine listening. But for the still generative big bang of jazz-rock, I recommend Spectrum – Anthology. which has most of the best of Emergency!, Turn It Over, Ego and The Old Bum’s Rush].

howardmandel.com

Subscribe by Email |

Subscribe by RSS |

Follow on Twitter

All JBJ posts |