Wynton Marsalis plays the immortal jazz of Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong tonight (Dec 29) 7:30 pm & 10:00 pm ET on Facebook and Livestream  live from Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola in Jazz at Lincoln Center, NYC. This is repertoire that the newly named CBS cultural correspondent relives better than anyone else, and it’s great to hear material written for the Hot […]

Archives for 2011

Inside, outside and beyond jazz heroes Sam Rivers & Don Pullen together

Sam Rivers and Don Pullen performed together — I had completely forgotten. “Capricorn Rising” is an 11-minute almost entirely duet track from a 1975 album of the same name. And in the ensemble Roots the two were joined by saxophonists Arthur Blythe, Chico Freeman and Nathan Davis, bassist Santi Debriano and drummer Idris Muhammad, recording the […]

Don Pullen, late pianist with an arts exhibit tribute

December 26 is a birthday I share with some great musicians — John Scofield and the late Quinn Wilson, for two. But yesterday I was thinking of a Christmas baby: pianist Don Pullen, 12/25/45- 4/22/95. A Don Pullen Arts Exhibit opens today in Roanoke, VA, his home town, produced by the Jefferson Center and Harrison […]

Sam Rivers remembered, recommended

Sax and flutist Sam Rivers called me a few months back, out of the blue, from his home near Orlando. “This is Sam Rivers,” he announced, Oklahoma-born voice at age 89Â 88 somewhat husky but energized — like his horn sounds. “I want to say I’ve played jazz with everybody from T-Bone Walker to Dizzy Gillespie, […]

Santa must wear earplugs

I’ve recovered a vintage JBJ posting from the archive, December 2008 (hence the reference to waiting for the end of the Bush administration. Still waiting. . . ) Yuletide music in the U.S. hasn’t gotten better since I first posted this, but it’s not for lack of song programmers scraping the bottom of the barrel. […]

Last ditch impressive gifts for fans beyond “jazz”

I refrain from abject product endorsement — but The Jazz Icons Series 5 is my no-fail recommendation for those favorite (weird?) aunts or uncles obsessed with “culture” — for parents who space out listening to long, wordless music from their decades’ back youth — for snobs who should meet vernacular jazz in its noblest and most durable […]

Wynton on CBS: the Artist as Cultural Correspondent

Wynton Marsalis has in one swoop become the world’s most prominent jazz journalist. The 50-year-old trumpeter, composer, bandleader, winner of multiple Grammys in multiple categories, author of several books on jazz (all but one co-written), artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, world-traveling ambassador of the American experience, holder of uncountable awards, degrees and honors, […]

Week before Christmas, NYC listening beyond jazz

Richard Bona introduces his Mandekan Cubano project at the Jazz Standard, Dec. 27 through New Year’s Eve — as I detail in my new CityArts-New York column. But from now through December 24 there’s other strong, new music to check out in, especially at Roulette in Brooklyn. Tonight (Dec. 15) and tomorrow (Dec. 16), trumpeter […]

Favorite recordings, 2011 — many more than 10

Lists of top projects of the year are expected from arts journalism – my apologies for being so late this year, but I needed to re-visit many of the the 1200 cds and dvds I received as promotional samples from Thanksgiving 2010 – TG 2011. Â Here are some favorites — top 10 I’ve liked best, […]

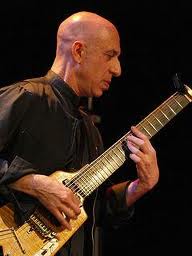

Elliott Sharp @ Roulette – way beyond category

No label exists for the music of composer-guitarist-saxophonist Elliott Sharp, who performed with two of his Carbon concept ensembles at Roulette in Brooklyn last week. In both quartet (Sharp on 8-string guitarbass with electronic processing, curved soprano and tenor saxes, and musicians playing electric bass, prepared harp and drums) and septet (the quartet plus second […]

Orchestrating improvisation

My new CityArts column is about the wave of conducted orchestral improvisation currently sweeping New York City  — with Karl Berger’s Stone Workshop Orchestra and Lawrence Douglas “Butch” Morris’s Lucky Cheng Orchestra wrapping up their lengthy Monday night runs, Elliott Sharp reconvening Carbon at Roulette, Greg Tate’s Burnt Sugar: The Arkestra Chamber at Tammany Hall in a benefit for […]

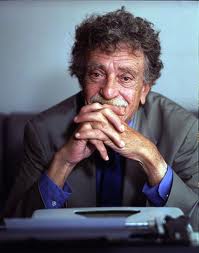

Kurt Vonnegut deserves better

Christopher Buckley’s New York Times Book Review frontpage piece on And So It Goes, Charles J. Shields’ biography of Kurt Vonnegut, is as lazy a bit of evaluation as it’s possible to pick up a paycheck for. I can’t tell from it anything about Shields’ book, and nothing about Vonnegut’s many novels, either. (See “jazz” content at […]

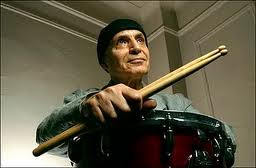

Drummer Paul Motian (RIP) talks, and why he matters

Drummer Paul Motian died November 22 at age 80. He was a unique sound organizer and constant actor on the jazz scene in New York City for nearly 60 years. He spoke to me for Down Beat in 1986 — an interview I offer in slightly different form below. Of course it doesn’t account for […]