March 06, 2006

Book 2.0

Episode 2: Game Over

In

episode 1:

[This

is the start of the book’s introduction.]

This

is a book about the future of classical music. It’s a necessary book, because

classical music is in crisis, and people have burning questions. Is the

classical music audience growing older? Will classical music disappear?

Many

people can get caught up in these questions —classical music professionals,

people in the classical music audience (who often love classical music even

more than the professionals do), people who like classical music but don’t go

to classical concerts (and might wonder why), and of course people who care

about the current state of culture. I’m writing this book for all these people,

including those who don’t know much about classical music.

( If you want to read the first episode of the Book 2.0, go here.)

But now, I’d better

state my own beliefs (which in any case keep sticking their heads out as this

introduction unfolds), and give my own answers to the big questions I posed at

the start. So here goes. Essentially, I think the game is over, by which I

don’t mean that classical music will completely disappear — that nobody will

compose classical pieces any more; that no one will go to music school to study

the bassoon; that opera companies won’t be staging Rigoletto for the four thousandth time (no, wait, maybe they really will cut

back on that); or that I won’t be able to go online and instantly download a

recording of the first Brahms piano sonata, as I did the week I’m writing this,

because I just couldn’t wait to hear it.

(I found it in three

places, in case anybody’s curious: emusic.com,

the Naxos Records website — where, with their Naxos Music Library service, I can

stream their entire catalogue — and of course iTunes, which

offers three recordings.)

But what will disappear, I think, is the classical

music world as we know it today, with its loyal audience gathering in silence

to hear musicians in formal dress play Brahms, while printed program notes

offer scholarly disquisitions on his work.

How startling will

these changes be? Very startling, at least to some people.

A decade ago, the But

more on that later in the book. I sympathize, I have to say, with everyone who’ll mourn the passing of

the classical music world we know, since I grew up in it myself, and as a

composer, I often feel I’m writing music that belongs in it. These emotions,

too, will find a place in what I’m writing here. And they lead me to ask, with

maybe more force than I expected, why all these changes should be necessary.

The answer, of course, is very simple —the old ways aren’t working. Why

else would we have a crisis? And the old ways aren’t working, first of all, financially. The

classical music world, as we’ve known it now for generations, is moving toward

a sea of red ink, in which it won’t be able to support itself. The audience —

getting back to the first of the questions that I asked at the beginning — really

is growing older. Data from the National Endowment for the Arts pretty much

proves that, at least for the And if the audience is growing older, then it’s very likely

growing smaller. Older people, in their last years of concertgoing,

aren’t being joined by younger people starting to attend. So as time goes on,

the audience will shrink. As it happens, there’s another theory, which says the

older audience is good news, not bad, because it means that people now live

longer, and will go to classical concerts for many more years. But that’s not

likely. If this were the only reason that the age of the audience is going up —

because there are more older people in it — then the

age distribution of the younger portion of the audience wouldn’t change. If,

let’s say, we went back 10 years, and found that twice as many people in their

forties went to concerts than people in their twenties, we’d expect to see the

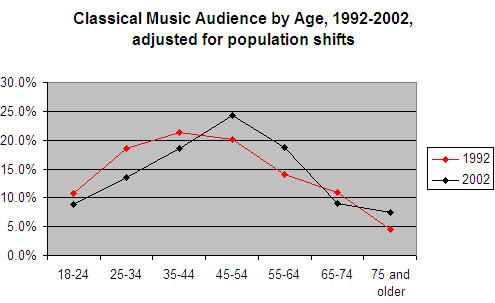

same thing when we look at the audience today. But we don’t. Instead, almost the

entire curve has shifted to the right: Yes, there’s a small increase in the percentage of the

audience that’s 75 or older, but it’s more than offset by the marked increase

in people 45 to 64, and corresponding decrease in people 18 to 45. And in fact there’s also data that suggests — rather

strongly — that the audience is getting smaller. This comes from many places,

for instance from anecdotal and newspaper reports of shrinking sales for

classical concerts at performing arts centers (these come almost unanimously

from everyone involved in these events); from anecdotal and newspaper reports

of declining ticket sales at major opera companies; and from figures gathered

both privately and by the American Symphony Orchestra League that show

declining ticket sales for orchestras. Though here’s a notable discrepancy. The League’s figures show

a peak in the 1996-97 season, with a drop thereafter; the private figures show

a steady drop since 1990. Which is right? Well, why not both? Because the numbers measure different things. The League’s

data speaks for 1200 orchestras, and the private figures only for the largest

ones; more importantly, the League’s numbers are for attendance at all

orchestral events (including Christmas music, and free concerts in the park on

the Fourth of July), while the private numbers zero in on tickets sold for

serious classical performances. And the serious classical performances have

been losing more of their audience. So then aren’t orchestras having trouble

with their core mission — performing the masterworks of the orchestral

repertoire — and making up the slack (whether or not they consciously planned

to do this) by expanding into other areas, like holiday concerts, pops events,

and sold-out performances of the music from Lord

of the Rings? And wouldn’t this support my contention here, that the old

ways aren’t working, and that things will have to change? (Whether Lord of the Rings — and, more generally, other populist events

—would be the only change I’d want to see would be another story.) And then along with the aging audience and the falling ticket

sales inevitably comes a financial crunch. That’s not just because falling

ticket sales bring in less money; there’s also a snowball effect. No classical

music organization can support itself on ticket sales alone; they all have to

raise money, first of all from private donors. And where do those donors come

from? Most of them are ticket-buyers. So if ticket sales are falling, donations

will fall, too. But now pull back for a larger view. Classical music

organizations also raise money from the community at large,

and above all from corporations, foundations, and all three levels of government,

local, state, and federal. So if fewer people are buying tickets to classical

concerts, then fewer people care about them. And if fewer people care, then of

course money from any source is going to be harder to find. Which, once more, is exactly what’s

happening, while the expense of putting on classical performances keeps rising.

Orchestras therefore report (at least in private) that they’re facing

structural deficits, or in other words that they see a long-term pattern of

expenses rising faster than income. Their private projections can be very dire.

I’ve heard a prominent person in the orchestra world say, safely out of the

public eye, that a representative large orchestra (which he didn’t name) might

have so large a deficit by 2010 that it would have to go out of business. And

I’ve heard another respected orchestral say that, if present trends continue,

all orchestras will be playing to halls only 20% full 10 years from now. And

while it’s true that these prophecies come with disclaimers attached (the

conclusions are only tentative; more studies need to be done), most orchestras

act, at least in private, as if the danger was real. The first part of this book will ponder these financial horrors,

along with related crises, like the declines of classical radio, classical

recording, and media coverage of classical music. [I should add that my

analysis is still preliminary. I need more data, especially about opera

companies and chamber music concerts.] And

I should say that catastrophe hasn’t hit yet. There are still bright spots in

the picture — kids still are learning to play classical music, and so both

youth orchestras and music schools are thriving. Classical downloads sell better than classical CDs. Classical concerts can still be exciting; some of them still have sold out houses. But the collapse (if

that’s what it’s going to be) has begun. The trend is downward, and so empty

seats are sometimes very noticeable. Some concerts, even in healthy times, sell

more tickets than others; but if ticket sales are generally falling, the events

that sell the least soon start looking very

empty. And projections for the future, as I’ve said, look even worse. In

the next episode, which goes online March 20: the

introduction to the book continues, with an outline of some other problems the classical

music world will have to face — its growing distance from contemporary culture,

and an uneasy blankness at its core. (Readers of Book 1.0 already know

my thoughts about that last point.) If you'd like to be notified by e-mail when new episodes appear, please subscribe to this book! Just click on the link; you'll see a blank e-mail form. Just put "subscribe" in the subject line, and send it off to me at gsandow@artsjournal.com. Here's the text of episode 1:

(This is the first episode of my second version of this book on the future of classical music. It's the beginning of the introduction to the book. Like the older episodes, it's an improvised first draft, and will very likely be revised, maybe extensively revised. But I trust it's a draft of something tighter and more focused than the last version -- a draft of a book that starts by asking (much more directly than the first version ever did) what's wrong with classical music, and then goes on to say how I think the problems might be fixed. See the outline at the left for more details.) This

is a book about the future of classical music. It's a necessary book. Not,

maybe, necessary for me to write, though I've made a specialty of this subject,

and find myself getting hired to write, speak, teach, and advise about it;

certainly I've got a lot to get off my chest. But someone, surely, has to

write a book like this. Classical music is in crisis; nobody knows whether it

can survive. And there are burning questions to be answered. Is the classical

music audience getting older? Will it die off, and not be replaced? Can we find

a younger audience? And why, exactly, should we be having a classical music

crisis? Has our culture degenerated? Is it now too shallow -- too noisy and

dumb, too frenetic, too careless -- to support cultivated musical art? Or has

classical music just fallen behind the rest of the world, and gotten out of

date? These are big

questions, and I can imagine that four kinds of people might get caught up in

them. First, of course, would be people who work in the classical music

business, who have to care, because their careers depend on it. Though it’s not just their careers. Anyone who knows them

knows that they love classical music —

many of them, especially the ones with high-level jobs in classical music

institutions, could make more money doing something else — and if the classical music world really does

collapse, they’ll very likely be heartbroken. (The musicians, I’d think, would

keep on playing, but now with any chance of ever making a living.) And then next on the

list come the warm and often gentle people who go to classical concerts, and of

course to the opera. They’re mostly in their fifties, sixties, and seventies,

and in everybody’s worst-case scenario they’ll soon enough vanish, leaving

concert halls empty. Many of them, I suspect, love classical music even more

than the professionals do; certainly their love can be achingly pure. Not all

of them see very deeply into the quality of each performance they hear, and

they might not care all that much what happens behind the scenes; but they do

love the music. They’re also, at least in my experience, the people in the

classical music world who worry most about the lack of any younger audience,

maybe because they’re the ones who most clearly see, at all the concerts they

go to, that they’re getting older, and that younger people just aren’t showing

up. And third come people

who like classical music well enough — they might listen to it on the radio, and

maybe they’ll buy classical CDs or downloads — but don’t go to classical concerts.

(Though they might bring a picnic basket when the New York

Philharmonic plays free concerts in And

so this book would be for her, just as much as for my colleagues in the

classical music business and the good and loyal people in the classical music

audience. There’s also one more constituency I’d aim at, and that’s anyone

interested in the current state of our culture, meaning especially (but not at

all exclusively) scholars and cultural theorists, along with civilians who like

to read about culture and cultural theory, everyone, in short, who might care

about the long-term meaning of everything I’m talking about. No matter why

classical music might be threatened —

whether it’s because culture is rotting away, or because classical music has

stagnated — what’s going on is

an ongoing, large-scale, long-term cultural shift. Part

of that shift, of course is the rise of popular culture. There's a lot written

about popular culture, about its meaning, worth, and ascendancy (including,

recently, Stephen Johnson's wry and important book Everything Bad is Good for You, which insists — right in the face of everything many

people in the classical world believe —

that popular culture, far from being dumb, is smart, and getting smarter). But

there's much less written about where classical music fits in this ongoing shift,

and too much of what does exist is more or less worthless, because the writers

don’t know much about popular culture, assume that it’s junk, and then have a

laughably easy time proving classical music’s crucial cultural worth by showing

that, guess what, classical music isn’t junk.

(There have, though, been some terrific critiques of the classical music

world’s exaggerated sense of its own importance, and, most important, its idea

that classical music has timeless value purely on abstract musical terms, and

stands aloof and alone, unaffected by the shifting winds of cultural change.) So

I’m writing this book for all of these people, all the four groups I’ve

mentioned, plus anyone else who wants to come along for the ride, even if they

don’t know anything about classical music. That, I know, is going to be a tricky

balancing act — to address

both the concerns of people inside the classical music world and the curiosity

of people outside it, to speak equally to heartbroken (and sometimes angry)

fans and to skeptical nonattenders, to cultural

theorists and to people who passionately love classical music but might not

care about cultural theory. But I think I can manage that, and, best of all, I

think that simply by trying I’ll give the book some extra verve. I

hope, too, that I can establish the value of classical music, in terms that

both insiders and outsiders can accept, and without needing to take down

popular culture in order to do it. To do this, I'll have to talk about the

position of all the traditional high arts in our current culture, another

contentious topic that needs to be better understood. And I'll also have to

talk about music itself, which will be a relief, after all

the theoretical talk about culture, not to mention everything I’m going to have

to write about classical music’s financial distress. What, in any case, would a

book on music be worth, if it didn’t have any music in it? (Maybe I should even

write a piece of music — I’m a

composer, after all — and

distribute it along with the book, to demonstrate exactly what I think music

should be.) I trust, by the way, that I can write about classical music

non-technically, so I won’t lose uninitiated readers, and maybe in doing this break

down the unfortunate notion that classical music is by nature complex, and can’t

be understood without special study. Maybe, by the time the book is done, I’ll have

given people who don’t know classical music a better idea of what it’s about — and maybe I’ll also give old-line classical

music people a better idea of what pop music is. Even if I just manage those

two things, I’ll be happy. But

now, I think, I’d better state my own beliefs (which in any case keep sticking

their heads out as this introduction unfolds). I’d better give my own answers

to the big questions I posed at the start. So here goes. Essentially, I think

the game is over. The classical music business won’t be able to exist much

longer in its present form. That doesn’t mean that classical music will

disappear (though some of our classical music institutions — orchestras, opera companies, and

the rest, including some name-brand groups — might well collapse). But I think classical music will have to

learn to understand itself in a new way. It’ll have to transform itself both

externally, in the way it presents itself to the world, and internally, in the

way that it’s taught, played, analyzed, and composed.… Episode 2 is, of course, the continuation. Posted by gsandow on March 6, 2006 01:07 AM Mr. Sandow's writing is important enough to me ( I'm a composer ) to save this and to send it to all my musician friends. Posted by: Robert Jordahl at March 6, 2006 07:16 AM There may be fewer sit down concert audience listeners, but there are a great many more classical music listners (and lovers) than those in the few cities that support professional symphony orchestras. Funny that you failed to include Rhapsody in your list of sources for the Brahms sonata. Classical music is alive and well and very popular at that site, and not only is Brahms readily available but so are the other classic composers. I'd read your "book" but the premise is a bit silly, so what follows can't be but more of the same. No art form is ever in static condition. Every thing is in evolution. With communications now so easy, streaming of concert music is available to all people and the need to flock to a concert hall for refreshment is less important than it was. The symphony orchestra however, will remain as the fountain head from which recordings will flow. And always there will be people to support those orchestras, even though that funding may decline, and music makers may have to adopt as they always have. The urge to make the music will never pass away. It is basic function of human existence. The need to support those who make music is likewise fundamental to human experience. The game ain't over, it is only changing. But in the end, the game will go on, just as it goes on changing. Posted by: Richard W. Galloway at March 7, 2006 03:55 AM ". . . most orchestras act as if the danger was real." I wish thay were true -- it looks to me like too many of them don't. They act as if things are hunky-dorey, as if things can keep going as they are -- sort of like that Talking Heads song, "Heaven is a place where nothing ever happens." They deny that audiences are declining, and they deny that the audience is aging -- which amazes me. I mean, the whole country is aging, wouldn't it be a miracle if the classical audience wasn't getting older? Of course, the NEA stats say the classical audience is not just getting older, it's aging at a much faster rate than the US population, and is the oldest of all performing arts audiences. It seems to me we have two choices. We can continue putting a smiley-face sticker on the problems, denying their existence and saying "Crisis? What crisis?" Or we can acknowledge them and start doing something about them. I submit the former does a disservice to the art we love, and the latter is the only responsible choice. And it's not like we don't know what to do. I think a lot of the diagnosis is pretty well-known, the prescriptions are pretty clear. The problem is we're not doing them. And that's what fascinates me -- what keeps the orchestral world from evolving? Why is there such resistance? Of course, it is evolving despite itself, in ways it really doesn't want, as evidenced by the statistics you cite. It reminds me of George Carlin's quip about the "Save the Planet" movement. "The planet will be just fine, it's survived a lot" he said. "We humans, though, are toast." Music will be fine, it's just the orchestras that are denying their way into the past tense. Posted by: Anonymous at March 8, 2006 07:08 AM I have a couple of comments/questions about these statistics you are quoting here. I wonder if the increase in the age of the classical music audience could be explained by a shift in the average age of the population at large. The chart you show makes me want to see it compared to a chart of the change in the average age of the general population. I think that the baby-boomers lie right in the range that appears to be increasing in classical audiences, so that might at least partially explain the statistical shift. On another place in your blog a chart shows the somewhat surprising fact that the number of classical concerts has been increasing. I wonder if that might explain anecdotal evidence of "empty halls" and increasing deficits. It seems that many organizations (not just musical) define success as a constant state of growth and expansion, rather than maintaining a successful status quo. Perhaps classical music institutions should face the fact that they need to stop expanding or actually reduce the number of concerts they do? I also can't help but think that the outrageous demands made by directors and administrators, as well as musician unions. When I see what music directors and members of high profile orchestras make for a living (Boston is an example which springs to mind), it seems to explain a bit about why it so difficult for these organizations to balance their books. The gap between rich and poor in the classical music world seems to be rather extreme. Perhaps the salaries need to reflect the reality of increased options of entertainment in the 21st century. Anyway, just some thoughts, good luck with the rest of the book. Posted by: Dan VanHassel at March 11, 2006 07:46 PM this is trully a tragic state of events right now. Music is not appreciated by anyone and that really bothers me. I am 15 years old and I spend a lot of time trying to introduce real music to the kids in my school who listen to the new stuff that can barely be called music. Music is a reflection of my life as a whole, especcially classical music so if you have any ideas for me I would appreciate your input Posted by: josh at March 12, 2006 07:32 AM

COMMENTS

Dan, thanks for this. Another comment addressed your question about the aging of the entire population -- the classical music audience is aging faster than the population as a whole. My chart, in any case, was based on figures adjusted for the change in age distribution among the general population. That is, I allowed for those changes.

I suspect that the increase in numbers of concerts is due to events in the community -- that is, more school concerts, more parks concerts, things like that. Or else things like the Lord of the Rings symphony, added to the normal schedule (and typically selling masses of tickets).I haven't noticed orchestras doing more serious classical events.

As for "unreasonable" pay demands -- orchestras may well calculate that the loss in ticket sales, if they had non-famous music directors, would more than offset the cost of hiring a famous one. It's hard to argue with the market here. This is what these people get paid, and if they don't get hired in the US, they'll just stay in Europe.

Musicians' salaries are more negotiable, and of course many orchestras are trying to negotiate them (downward). That may seem reasonable from a business point of view, but it's a severe shock to the musicians, especially those who entered the business 20 years ago, and now have mortages and kids in college, all possible under the old financial ways, and understandably hard to give up now. Are we really telling musicians they can't get paid like professionals in other fields? Maybe here it's once again hard to argue with the market -- maybe it's just not possible to employ so many musicians at current salary levels -- but to call the musicians "unreasonable" for wanting to live the way other professionals do seems quite unfair. My suggestion to Josh is that he take more interest in the music his friends like. Hard to see why they should like his music when he doesn't have anything good to say about theirs. Not that he's in an easy position, since he genuinely doesn't like that music! I remember when I was in school and felt the same way.

Does anyone have any other -- maybe better -- ideas?

Post a comment

Tell A Friend