Leans into a black hole. (He/she who digs newspapers is an ongoing series.)

OSCAR TUAZON

“BLACK HOLE”

2003

Newspaper, tape, paint

250 x 900 x 600 cm

Edition: 1

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Leans into a black hole. (He/she who digs newspapers is an ongoing series.)

OSCAR TUAZON

“BLACK HOLE”

2003

Newspaper, tape, paint

250 x 900 x 600 cm

Edition: 1

Curators are entitled to put whoever they can get (and the director is

willing to defend) in a show. I find it inconceivable, however, that a

Northwest curator would mount an animals-in-art exhibit that failed to

include Seattle’s Sherry

Markovitz.

Not in Rock Hushka’s The Secret

Language of Animals at the Tacoma Art Museum:

Encrusted over the

Encrusted over the

surface of Markovitz’s fiberglass molds, gourds and papier mache are

many

thousands of tiny glass beads woven into streams of colored light and

bordered with oil paint, leather and velvet, foil and nails, amulets and

jewels.

All that complexity becomes a simplicity in its realization.

Her sculptures are presences that come from time slowed down. Her deer

and bear heads aren’t trophies but relatives, linking us to all beings

who lean into light and live by breath.

In the Northwest on this

theme, she is too big to ignore. Ignoring her becomes a statement, and

that statement serves as the elephant in the room, invisible but

determinative, sour and eccentric.

Hushka’s exhibit is still a pleasure. (My review here.)

The more time I spent in it, however, the stronger became the

conviction that a good effort could have been a great one, given certain

additions and a lot of deletions. The exhibit wants to be all things to all

people. Hushka is too good a curator not to know that he padded in the

interests of popularity. A starker survey would give the exhibit’s core

samples a chance to reverberate in each other’s company.

First, almost everything made

before 1960 needed to go. In this show, contemporary art sets the tone.

With the sole exception of Audubon’s hand-colored engraving, Three-Toed

Woodpecker from 1832 (a perfect accompaniment to Justin Gibbens‘

present day riffs on it), the mostly modest art from earlier eras needs

its own space in another show. Most of these prints and small paintings function

as florid digressions in sentences that want to be muscular.

Second,

Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora C. Mace‘s eight cast glass sculptures from Bird

Pages are a dead spot where the ball won’t bounce, far from their

best work. One might have slipped by, but twelve?

Another big chunk that needed to go: Just say no to

the corny, fey, conventionally literal and the whimiscal.

Had the muscular been achieved, there are a few possible additions that could have augmented it, besides, of course, the essential Markovitz. The ones below would have been easy to get in Tacoma, not, in other words, the impossible dream.

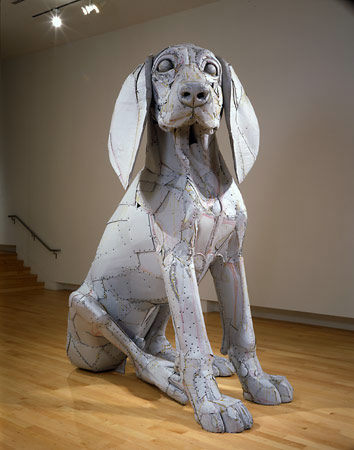

TAM owns Scott

Fife‘s LeRoy, 2004. 118 x 78 x 120 inches, archival

cardboard, glue,

screws.

Of course it belongs

Of course it belongs

where it is, in the exhibit, but it would have been swell to offer a darker

side of Fife as well, something less ingratiating than the dog that

normally sits as a greeter in the lobby.

Wer

Wulf

25 x 25 x 34 inches, archival cardboard, glue, screws, 2007

The

The

touch of the mythological would not have gone amiss.

Michael

Spafford The Iliad #19

woodcut, 2004

image 12 x 20″, paper size 19¾ x 26″

I

I

would have appreciated something from the heart of old Hollywood.

Grant

Barnhart, Elizabeth Taylor, acrylic on canvas, 12 x 12 inches

An animal-in-art exhibit is a good place to explore

An animal-in-art exhibit is a good place to explore

the anguish of

childhood.

Pat

De Caro, Toilet with Snake, oil/glassine, 2003 42 x 40″

How about touching on the theme of the kinks in the Wild West?

How about touching on the theme of the kinks in the Wild West?

SuttonBeresCuller Beast of Burden II

2003

C-print on Sintra

18 x 24 inches

Edition of 5

Every exhibit is a

Every exhibit is a

series of

moments. In great ones, the moments cohere into an overwhelming

conclusion. Hushka’s had the makings of great but settled for pleasing,

well below his capabilities.

Through June 27.

With a lifelong affection for Desolation Row, I contemplate the abandoned Fun Forest at Seattle Center with pleasure. Cracks in the asphalt and gaping holes where the rides used to be are not an amenity to be taken lightly. For that reason I’m sympathetic to those who are outraged that a Dale Chihuly glass house and green shed with garden might supplant an excellent place to shoot an end of the world movie. They say they want grass, but tearing up the concrete and seeding it with what Walt Whitman called the lovely hair of graves will cost millions. Millions the city does not have.

Yoko Ott would prefer a botanical garden. Alas, we have one already and

can’t afford to take care of it. (If ifs and buts were candies and nuts, what a Merry Christmas we’d all have.)

To wit:

To wit:

The City of Seattle is scrambling to cover a multimillion dollar budget deficit. Now, people close to the situation say Parks and Recreation will take the biggest hit, with first cuts planned as soon as July, according to the Associated Recreation Council, an independent non-profit that partners with the city department.

“Community members need to share their personal stories with the Mayor and City Council members if they expect the doors to stay open and the parks maintained,” said Christina Arcidy, Project Coordinator for ARC, in an e-mail sent to CHS. “There are no public meetings or formal requests for public comment, so individuals must reach out to their elected officials and start a dialogue if they want to have an impact.”

Cuts could include lawn and mowing maintenance for all Seattle parks. Pools and public facilities in all parks, including Volunteer, Cal Anderson and Miller Parks, will not be open to the public any longer, or may have shorter operation hours.

While none of the major planned cuts have been confirmed by Parks or the city, CHS received confirmation from a City employee with knowledge of the situation who asked to remain anonymous about the severity – and certainty – of the cuts being planned. (more)

Surely better times await, and then we’ll be stuck with a Chihuly center, right? Well, wrong. The privately funded venture would have a 5-year-lease. If Chihuly fails to dazzle the public (and bring in from $300,000 to $500,000 annually to city coffers), his glass plug can be pulled, leaving the building that’s already there and a garden. (Even if he’s a raging success, the lease will terminate at 20 years.)

For these reasons and so many more, anti-Chihuly forces, please continue to fight the good fight. Save cracked asphalt for the kids. They’ll thank you when they grow up to be disaffected hipsters. I for one admire your moxie and your effectiveness. The mayor sounds as if he’s leaning toward siding with you, as well he should. You helped elect him.

In the meantime, Bobby D. has the closer:

Here comes the blind commissioner

They’ve got him in a trance

One hand is tied to the tight-rope walker

The other is in his pants

And the riot squad they’re restless

They need somewhere to go

As Lady and I look out tonight

From Desolation Row

In response to this post, Charlie Kitchings sent me the video below. Being ArtsJournal’s video editor, I would have posted it on AJ’s main page, but the video’s credit line extends too far right. It would cut into the blogger’s corner, interpreting somebody and no doubt stimulating complaint.

Rathman creates his own rumble in the jungle: drawing vs photos, drawing vs film. Drawing wins.

Zaire: David Rathman Project – Muhammad Ali Rumble in the Jungle 1974 from Tom DeBiaso on Vimeo.

If you were going to get a pet

What kind of animal would you get?

A soft-bodied dog, a hen

Feathers and fur to begin it again

when the sun goes down and it gets dark

I saw an animal in a park

Bring it home to give it to you

I have seen animals break in two

You were looking for something soft

And loyal and clean and wondrously careful

a form of otherwise vicious habit

could have long ears and be called a rabbit

Dead died will die want

Morning midnight I asked you

If you were going to get a pet

What kind of animal would you get?

The Secret Language of Animals is not a secret. Instead, the exhibit of that title at the Tacoma Art Museum is almost entirely about us. Ever since humans stood up to look around, we’ve made images of animals as shipping containers addressed to ourselves. From the bull on the wall of a cave to the shark in a gallery, it’s a myriad-minded stream of us projecting into them.

The stream never ends, and neither does our interest. Through animal depictions, human consciousness parades. As a theme, it’s a hearty perennial, hard to kill. The good news is, Tacoma doesn’t. Curated by Rock Hushka, The Secret Language is, like his currently running A Concise History of Northwest Art, a winner.

Unlike A Concise History, however, The Secret Language is a baggy monster, drawn from the museum’s collection and beyond it, from the 19th century to the present. From its title to the structure of its categories arranged in zoo fashion, like with like, Hushka’s attempt to order his offerings fails to convince. What saves this exhibit are the objects in it. There are too many of them crammed together, but the grace and force of their diversity creates a gravitational pull of interest that sweeps the audience along.

There are three giant Deborah Butterfield‘s in one spacious gallery. Her horses are drawings in space. The best are lumbering but light, well bred from wreckage. These three are fine indeed. Why didn’t the museum give her the entire gallery? The small prints on the wall (Stubbs, Delacroix) are hedged bets. Hello Tacoma Art Museum: If you’re highlighting an artist, go ahead and give her the space. If she needs Stubbs to matter, she doesn’t.

Vanessa Renwick Longhorn, 2010

16mm to video loop

shot at Patty Pink Chap’s Ranch in Montana, from the Oregon Department of Kick Ass Renwick’s Longhorn is a rarity, a piece about an animal that offers nothing but the animal. Bill Viola’s buffalo breathing steam in the morning is an emblem of spirit, but Renwick’s shaggy star offers only itself. No meaning beyond its own adheres. With an economy of motion that makes sense in one so heavy-headed, it stares, turns, grazes and steps to the side, over and over in a repeating loop. It’s a massive utterance on a wide plain, and it has nothing to say to us.

Renwick’s Longhorn is a rarity, a piece about an animal that offers nothing but the animal. Bill Viola’s buffalo breathing steam in the morning is an emblem of spirit, but Renwick’s shaggy star offers only itself. No meaning beyond its own adheres. With an economy of motion that makes sense in one so heavy-headed, it stares, turns, grazes and steps to the side, over and over in a repeating loop. It’s a massive utterance on a wide plain, and it has nothing to say to us.

Elizabeth Sandvig‘s Peaceable Kingdom series was inspired, of course, by Edward Hicks. Unlike Hicks, she has no hopes of lions lying down with lambs, but she likes the lights and darks of their colored shapes and suggestive densities. Instead of family, the deer is as distant as the sun, and the black bear with a possessive paw on the flank of a sheep cannot be trusted.

Sandvig, Peaceable Kingdom at Night, 2003 oil/canvas 24 x 32 inches

Soaring past William Wegman’s dress-up dogs is Fred Muram‘s eating breakfast. The artist calmly dips his spoon around his dog’s lapping tongue and eats as if there’s nothing odd in doing so. He’s Buster Keaton who sees the train coming but doesn’t leave the tracks. Muram divides the world in two: those who know a train with a tail won’t hurt them and those who are fearfully freaked out.

Soaring past William Wegman’s dress-up dogs is Fred Muram‘s eating breakfast. The artist calmly dips his spoon around his dog’s lapping tongue and eats as if there’s nothing odd in doing so. He’s Buster Keaton who sees the train coming but doesn’t leave the tracks. Muram divides the world in two: those who know a train with a tail won’t hurt them and those who are fearfully freaked out.

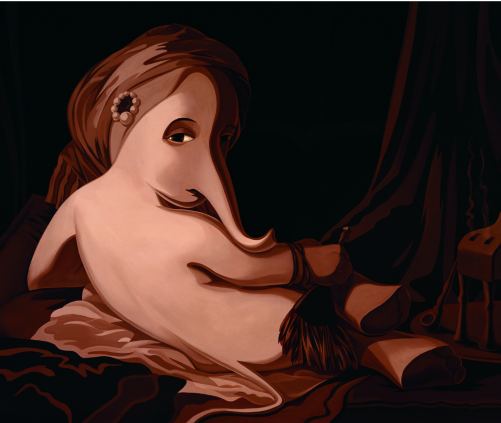

Muram Sharing a Bowl of Fruit Loops with My Dog, 208 Single channel video Dimensions variable In monochromatic sepia, Joseph Park‘s The Grand Odalisque takes

In monochromatic sepia, Joseph Park‘s The Grand Odalisque takes

Ingres’ boneless paintings of nude women (all flesh, little

structure), and sets not only the figure but the ground

around it in motion. Curtain, bed, tassel, turban, tail and trunk have a seamless flow. It’s a lost time looked at again with humor and a

strange, silky gravity.

Park, The Grand Odalisque, 2001 oil/linen 30 x 36 inches

I’m not sure that Malia Jensen‘s bronze bear would matter much without its title. With it, the animal is the epitome of a guilty party, confessing only when caught.

I’m not sure that Malia Jensen‘s bronze bear would matter much without its title. With it, the animal is the epitome of a guilty party, confessing only when caught.

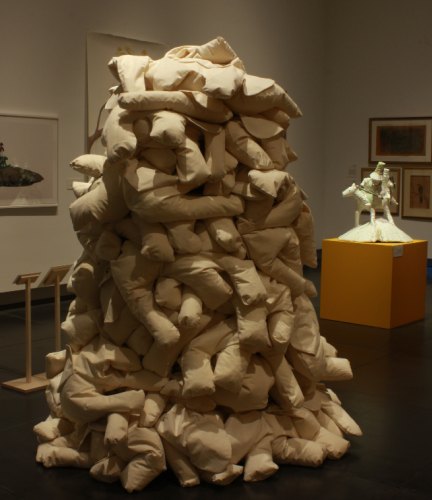

Jensen, Is This Your Cat? 2006 Bronze 22 x 14 x12 Hats off to Hushka for recreating Jeffry Mitchell‘s elephant pile from 1990, sewn by Tacoma Art Museum volunteers. Let’s hear it for battered hopes and dreams, for what goes soft and slack and lies discarded in a sweet heap.

Hats off to Hushka for recreating Jeffry Mitchell‘s elephant pile from 1990, sewn by Tacoma Art Museum volunteers. Let’s hear it for battered hopes and dreams, for what goes soft and slack and lies discarded in a sweet heap.

Mitchell, The Pile of Elephants, 1990 recreated 2010 Muslin and Styrofoam, 114 x 108 x 108 inches. (Claire Cowie’s Villagers on Horse, 2004-05 in the rear)

Richard Hart paints marsupial girls.

Richard Hart paints marsupial girls.

Hart The Poetic Truths of High-School Journal Keepers, 2009

Maki Tamura‘s painted paper constructions can be overworked. Not this one, whose image fails to do it justice. The incredible lightness of its being evokes Fragonard.

Maki Tamura‘s painted paper constructions can be overworked. Not this one, whose image fails to do it justice. The incredible lightness of its being evokes Fragonard.

Tamura Circus 2009 watercolor paper Geoffrey Chadsey‘s paintings cannot be reproduced. Missing is the queasy subtly of the shading, the face and chest whorled like diseased tree rings, the way the small dog is actually more of a rat resting on the root of a cadaverous man.

Geoffrey Chadsey‘s paintings cannot be reproduced. Missing is the queasy subtly of the shading, the face and chest whorled like diseased tree rings, the way the small dog is actually more of a rat resting on the root of a cadaverous man.

Chadsey Pet 2010 watercolor pencil on Mylar

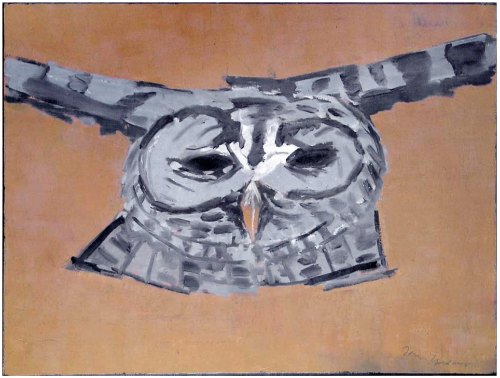

Air, desert, blue owl:

Air, desert, blue owl:

Joseph Goldberg Chaco 2005 encaustic on linen over wood 36 x 48 inches

Nice to see Justin Gibbens‘ birds hanging with one of Audubon’s, their source. Also worth the trip in this show are the Joan Brown’s, Muarizio Cattelan’s taxidermized dog sleeping in a chair (Good Boy, 1998); Morris Graves’ Walking Bird, 1943; John Baldessari’s Two Onlookers and Tragedy (With Mice) 1989; Kenneth Callahan’s dragonfly, late 1950s; Nole Giulini’s Mickey Mouse Organ, from 1994, several Claire Cowie’s, and Alden Mason’s Polka at the Public Market, 1987.

Nice to see Justin Gibbens‘ birds hanging with one of Audubon’s, their source. Also worth the trip in this show are the Joan Brown’s, Muarizio Cattelan’s taxidermized dog sleeping in a chair (Good Boy, 1998); Morris Graves’ Walking Bird, 1943; John Baldessari’s Two Onlookers and Tragedy (With Mice) 1989; Kenneth Callahan’s dragonfly, late 1950s; Nole Giulini’s Mickey Mouse Organ, from 1994, several Claire Cowie’s, and Alden Mason’s Polka at the Public Market, 1987.

Post to follow: the downside.

Now that journalism has succeeded in removing the journalists, losses are slowing and newspapers are at long last carrying on. Staffs are smaller, but the work goes on, not, of course, at the newspapers that folded early, such as my own, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, RIP March 17, 2009.

With 10 (or is it 8?) journalists replacing a staff of around 200, the PI continues online as a delusion of itself. This shallow but sprightly mirage continues to attract traffic. In doing so, it’s shaping up to be a financial success and a journalistic disaster. Why should publishers continue to pay (and put up with) writers, photographers, editors, artists and support staff who expect real salaries and health insurance, not to mention vacations and sick leave? Now there’s an alternative: a bare bones group with a bare bones compensation. What they can’t cover in their overheated work day can be covered by freelancers. The new meaning of freelance means you work for free.

The anniversary of the PI’s demise drew comment from former staffers. One thing you can say about journalists. They continue to type, even after their platform is gone.

One of my favorite PI reporters, Andrea James, now works in finance. From her new dollars and cents perspective, she finds her old paper lamentable. Her blog post, A well-run business it wasn’t, argued just that. What she left out is everything that mattered. In spite of shrinking resources, the PI that folded was the best version of itself in my more than two decades of employ there. The infusion of tough-minded young staff inspired those who’d been jogging in place to walk back into the world of who/what/when/where/why. The PI had the best chief editor I’d ever worked for, David McCumber, and a sane publisher, Roger Oglesby. (Sane publishers were not a given at the old PI.)

The wrong paper folded, leaving the fat-cat Seattle Times. Fine reporters work there, but the culture is one of Panglossian self-congratulation. Unless you piss Kool-Aid into the cup, you won’t be hired. To secure a slot you have to be blind to the egregious faults of the right-wing bully in charge, Frank down-with-death-taxes Blethen.

Nobody had to swear allegiance at the PI; in fact, skepticism was prized. A good newspaper is not a religion. Leaps of faith are discouraged. Instead, there is the daily hunt for big-game facts, for stories that are as accurate and fair-minded as the humans producing them are capable.

Where are we now?

What I think of as the PI Brain Trust is operating online as Investigate West, run by the great Rita Hibbard. The Seattle Post-Globe has turned into a good local news source. Plenty of former staffers have blogs, and the Post-Globe links to them, including my own.

A recent addition to the former PI staff blog roll is D. Parvaz’s well-named Something to Say. Fresh from a Neiman, she’s an Iranian-born Maureen Dowd: an enemy of cliche and advocate for clear thinking. I hadn’t realized how much I missed her voice until I started reading it again. Referring to new research on suicide bombers, she wrote:

A recent addition to the former PI staff blog roll is D. Parvaz’s well-named Something to Say. Fresh from a Neiman, she’s an Iranian-born Maureen Dowd: an enemy of cliche and advocate for clear thinking. I hadn’t realized how much I missed her voice until I started reading it again. Referring to new research on suicide bombers, she wrote:

As it turns out, strapping a bomb to oneself and killing others in

the process of detonating it isn’t anyone’s first choice.

Thought that Allah and the 49 promised virgins covered the topic? Reading Parvaz will take your mind to the gym. Her blog is my one-year anniversary present to myself, evidence that my peeps are everywhere, doing good work.

The question of hotness is not fruitfully addressed to art galleries. It pitches the discussion below the level of substance and implies that galleries have nothing better to do than titillate the fickle. Hotness runs in the same circles as buzz, a word I heartily dislike unless bees are doing it.

An exquisite example of the hotness-and-buzz genre is Tim Appelo’s Charlie’s Charge in City Arts Magazine, Seattle edition. I appreciate Appleo Appelo personally and enjoy his writing, but in visual art, which is not his forte, his insouciance is grating.

Appelo:

Why is Seattle’s most-buzzed art scene in Ballard instead of Pioneer Square? Only one Seattle gallery sent artists to December’s big Miami art fair (sic: Ambach & Rice was at NADA), and only one in the whole Northwest went to last month’s New York Armory Show: Charles and Amanda Kitching’s Ambach & Rice in Ballard. “Howard House had it, James Harris had it, Scott Lawrimore has had a long run,” says one gallerygoer. “Now Charlie is the new hot thing.”

Galleries are like Darwin’s finches. Those who find a niche are the most successful. Beyond that, whether Ambach & Rice is in Ballard or Pioneer Square, it’s part of the small community of Seattle art dealers who represent artists who matter.

Back to Appelo’s article. Ambach & Rice did not “raid” another gallery. What are artists in this construction, the loot? The artists in question came to the Kitchings, not the reverse. Then there are the personal remarks:

Charles Kitching has got youth, sharp looks, savvy and savoir faire. So some resentfully dismiss him as “Charlie Ka-CHING!”

That’s two anonymous quotes from the school of buzz. Unless there’s a compelling reason, everybody in a story should be on the record, including the casually snide.

Not that everybody on the record scored this time out. Assuming Portland dealer Elizabeth Leach was quoted fairly (I am going to assume that, given Appelo’s solid record in journalism), she offered a great example of double-speak: the official position first, followed by what she really thinks.

“It’s easier to be jealous,” says Leach, “but it makes more sense to be

supportive. Northwest galleries that go to fairs are ambassadors for all

of us.” She does think hard times have made the Armory “less

competitive. One could get into the Armory if one applied.”

Who is this “one” who could get into whatever fair one wanted?

Appelo appears to take a similar position:

How come other galleries didn’t go to the Armory Show? One reason is money. “It costs easily twenty to thirty thousand dollars to go,” says top Portland gallerist Elizabeth Leach.

One reason is money. Appelo doesn’t mention any others. Assume for a moment you’re a high school senior with a B average. You’re considering Podunk U or Harvard. One reason you’re not going to Harvard is money. Can anybody think of another?

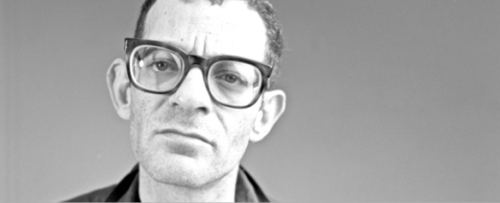

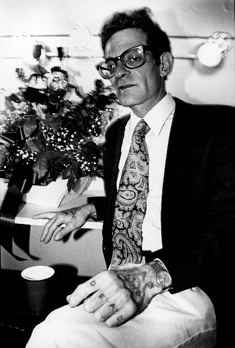

Speaking of himself in the third person, Jesse Bernstein once noted that he was “unemployed until the age of six; since then he has worked as a seeing eye dog for the spiritually impaired and as an emergency storm drain.”

Poet, performance artist, playwright, actor and friend of what he called the expendable people, he killed himself in 1990 in Neah Bay at age 40.

Photo Alice Wheeler

Most of his friends remember him not for his tragedy, which included mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction, but for his talent, his generosity, his steadfast loyalty and gleeful charm when the debilitating fog of illness lifted.

Most of his friends remember him not for his tragedy, which included mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction, but for his talent, his generosity, his steadfast loyalty and gleeful charm when the debilitating fog of illness lifted.

Small with bow legs and tattoos running up his arms, Bernstein had a

gravelly voice that became slurred when he neglected to put in his teeth

for his late-night phone calls to many willing and semi-willing

listeners.

They rarely needed to say anything. On the phone he said it all, ranging

across the history of poetics, the crimes of the Central Intelligence

Agency, the need for cheaper breakfast cereal and the search for a

sustaining form of God’s grace.

A well-edited collection of the range of his best work has yet to appear, although a posthumously released Sub Pop CD titled Prison briefly lit up the charts after selections from it played over the open sequence of Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers.

Peter Sillen’s recently completed documentary on Bernstein, I Am Secretly An Important Man, opens at The Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in North Carolina on Friday. It will screen as part of a Creative Capital film festival at the Museum of Modern Art on May 15 & 27. Sillen is still working on a Seattle release.

More Noise Please!

I live on a street

where there are many

many cars

and trucks

and factories

that pump

and bang and

grind all night

and day.

It is a miracle

that I can write poetry

or sleep or

talk on the telephone

or that

my lover will

visit me here.

[Read more…] about Jesse Bernstein – Secretly An Important Man

A Concise History of Northwest Art opens with Michael Brophy‘s clear cut along a logging road:

January, 1997. Oil on canvas, 78 x 95 ½ inches.

How brilliant it would have been to pair it with a Kenneth Callahan clear cut from the 1930s. Brophy has the sky drifting across mud furrows, the mountains serene in the distance and the exposed face of a cut tree shining low like a setting sun, but Callahan has the forest world convulsed, with no reassuring grace notes.

How brilliant it would have been to pair it with a Kenneth Callahan clear cut from the 1930s. Brophy has the sky drifting across mud furrows, the mountains serene in the distance and the exposed face of a cut tree shining low like a setting sun, but Callahan has the forest world convulsed, with no reassuring grace notes.

The Tacoma Art Museum does not have such a Callahan in its collection or it would have made an appearance. (Nor could I find one online.) Organized by the museum’s senior curator, Rock Hushka, A Concise History draws entirely from the museum’s holdings, which are impressive in their range and depth. Instead of a Callahan, what hangs beside Brophy is a meek Sidney Lawrence, probably from the 1930s, Mt. McKinley, Alaska, doing Lawrence no favors.

Hushka would have been well advised to give Brophy the entry wall. Experiences on the same frequency tend to fuse or spark. Lawrence is overwhelmed and deserves better. (His own space or a more sympathetic companion could have brought out his subtle delicacies.)

What a smart title. The word concise tends to cut off the inevitable complaints: Why not x? Surely if you have y, you need w. My only real compliant is that Huska didn’t take the word seriously enough. Exhibits at the Tacoma Art Museum tend toward salon style. They’re packed to the rafters. While I enjoyed this show, its density overwhelms the particular with the general.

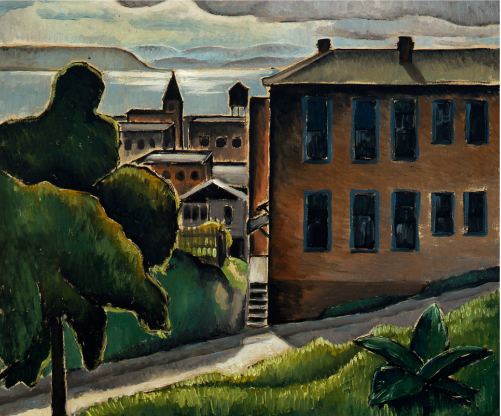

I like the exhibit’s first half of the 20th Century, which favors the lesser knowns, such as Ambrose Patterson, Peter Camfferman, Charles Heaney (It’s worth a trip to the Portland Art Museum to see the Heaney’s, lamentably underrepresented in Seattle), Walter Isaacs, Zama Vanessa Helder and Kenjiro Nomura.

Kenjiro Nomura,

Puget Sound,1933. Oil on canvas, 19 5/8 x 23 ¾ inches.

With light rimming his forms, Nomura conveys a quiet kind of Surrealism that predates Wayne Tiebaud’s. With painter Kamekichi Tokita, Nomura ran

With light rimming his forms, Nomura conveys a quiet kind of Surrealism that predates Wayne Tiebaud’s. With painter Kamekichi Tokita, Nomura ran

a sign-painting business before the war. In the 1930s they managed to give some work to Paul Horiuchi, who remembered painting large hula dancers and octopuses on billboards for them. The three would go out sketching on Sunday afternoons.

By the late 1930s such excursions were no longer safe. Horiuchi said he

and Nomura were on the University Bridge one day, drawing together, when

somebody reported them to the police as suspicious characters. After

investigating, the police told them to stop sketching outside.

Nomura and Tokita were deported to camp Minidoka in Idaho, and neither managed to regain their stride as artists afterward. Nomura had a lovely, dreamy style before the war,

turning Seattle into his own kind of paradise. With their

loose, sensuous line, his softly colored hedges and buildings seem to

be only pausing in space before floating away.

(For more on the theme of Seattle’s Japanese -American artists of the World War II generation, see review of Barbara John’s Views and Visions at the Seattle Art Museum in 1990.)

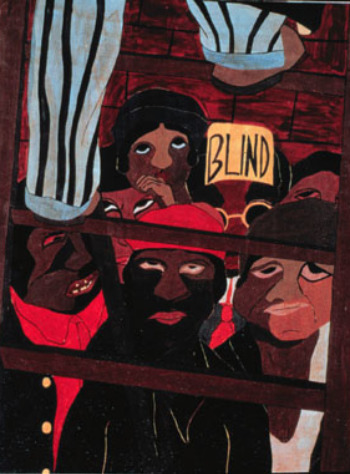

The thing about major figures, however, is that they tend to dominate. Morris Graves and Jacob Lawrence own the first half of this exhibit’s the 20th Century. Claiming early Lawrence for Northwest art is a stretch, as he didn’t move to the region until 1971, when offered full-professor tenure at the University of Washington.

Jacob Lawrence, Street Orator, 1936

When you’ve got it, flaunt it. The Seattle Art Museum does not own a Lawrence as good as this one.

When you’ve got it, flaunt it. The Seattle Art Museum does not own a Lawrence as good as this one.

Graves’ Chalice Holding the Stimson Mill, also from 1936, has the kind of fierce, light-struck landscape furrows that rival Anslem Kiefer’s, in deeper and far more radiant hues. Early Graves struck his colors like a gong, and they continue to reverberate.

The Mark Tobey here (Point of Intersection, 1949) is fine if a little academic, but representations of Guy Anderson and Callahan should have been left in the bins. Getting better Andersons could not be the impossible dream.

Rounding out the 20th-Century’s first half is Spencer Moseley‘s Olympia Landscape from 1947. Moseley is best known these days for arranging the Jacob Lawrence hire at the University of Washington, but what a lively painter he was. This painting does not even hint at the bebopping astringency of his mature work, but there’s real muscle in his iced blue waters.

Mid-20th Century art grips down and wakens in Seattle, seen here in the work of Michael Spafford, Robert C. Jones, Fay Jones, Alden Mason and William Ivey.

When Chuck Close met Willem de Kooning, Close told him it was nice to meet a man who’d painted more de Koonings than he had. One of those faux-de Kooning’s is in this show, from Close’s student days in the early 1960s at the University of Washington. (Only in the Northwest does evidence of this early source live on.)

As the exhibit edges towards the present, women begin to make more than an occasional appearance, including Marsha Burns, Alice Wheeler, Claire Cowie, Marie Watt and Susan Seubert.

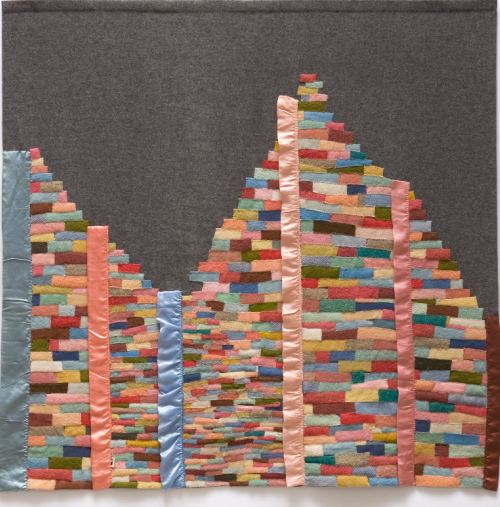

Marie

Watt, Tear Down This Wall, 2007. Reclaimed wool blankets, satin

binding, and thread, 61 x 64 inches

I love Seubert’s series, 10 Most Popular

I love Seubert’s series, 10 Most Popular

Places to Dump a Body in the Columbia River Gorge, from 1998. The museum owns all ten prints.

Seubert, Lewis and Clark State Park, gelatin silver

print, artists proof from an edition of 10; 16 x 20 inches.

In this telling of the Northwest tale, painters rule, not only in the past but in the present. That dominance represents a selective fiction. All we can ask of fiction is that it be convincing, and this one is, at least for the duration of the show.

In this telling of the Northwest tale, painters rule, not only in the past but in the present. That dominance represents a selective fiction. All we can ask of fiction is that it be convincing, and this one is, at least for the duration of the show.

Mark Takamichi Miller, Untitled, 1999. Acrylic on canvas, 72 x

64 inches.

Through May 23.

Through May 23.

Among the many responses to this post (thanks, everybody!), is Yoko Ott‘s dissection of the money involved, as well as an alternative plan for a botanical garden at Seattle Center, leaving aside the fact that there is a perfectly lovely botanical garden in Volunteer Park. I’m posting her comment here, because she is indeed good at math.

One point you keep reiterating repeatedly is the $500K in lease revenue Regina. The (more important) public-private debate aside, it’s the math I’ve been interested in. Generally speaking, I see the point, $500K/yr certainly seems better than nothing. However at that rate it sure seems like SC is on the loosing side of negotiating a fair market lease rate. Granted, I’m not a real estate agent, so I’m taking a guess here. But really, that $500K at 44K total sq. ft is about $11.25/sq ft. Being somewhat familiar with commercial lease rates I say the park has some wiggle room to leverage a more competitive rate to really bolster its income. I mean if this IS about earning the public $500K a year as you mention, and the trouble-shooting thought process is to go to the private sector–why not think the way the private sector does and NOT operate far below market value?? Which brings me to the fact that if one spreads the anticipated $20M initial TI investment, (that is cost to build the museum), across the max 20-year lease that’s 1M a year JUST to build it. Add to that annual rent and operating costs (not to mention inflation) divided by their projected annual attendance and it seems like a risky solvent venture–let alone a profit buster. (Did they talk to Mr. Allen?) So what if Mr. Wright saved some cash and gifted the park 10M in 20 $500K annual installments and the City figured out how to build the damn green space–and hey here’s an idea, a part of it could include a botanical garden, with you guessed it, a Chihuly exhibit. Charge admission to it, it would be a fair trade off.

an ArtsJournal blog