“The local bookshop is run by an Englishman and his wife who is about 20 years older than he, very cute, really, with dyed bright pink hair. They play chess in the corner and very much dislike being interrupted by a customer. The other day a man I knew went in to buy a book and asked for it timidly. Hugh, the Englishman, said, ‘Good heavens, man! Can’t you see I’m about to make a move?’ When I first went in this year the wife asked me in her jolliest way what I was doing now? Writing or what? I said writing, and she replied ‘Ha-ha–always something!'”

Jan.1, 1948 letter from Elizabeth Bishop to Robert Lowell, Words In Air

CAAF: New Year, new things

My friend R. recently introduced me to Tom Jobim’s “Águas de Março.” It’s a wondrous little song, and an especially nice one to listen to on a day like today, when you may find yourself back at a desk feeling simultaneously tamped down and stretched thin. Here it’s performed by Elis Regina (and provided with English subtitles). If you like it, you may want to get Elis & Tom — the album was new to me, but probably isn’t to many About Last Night Readers and, evidently, if you grew up in Brazil in the ’70s your house had a copy.*

* After seeing that last “if you grew up in Brazil in the ’70s” observation a few different places online, I’ve been amusing myself trying to think of what the album’s American equivalent would be, ubiquity-wise: Music Box Dancer? Jonathan Livingston Seagull? Aloha From Hawaii?

TT: Free at last

So read the title of an e-mail from Paul Moravec, composer of The Letter, that I received late last night. Here’s what it said:

I’m ready to unleash Subito [the publisher of The Letter] on this document and get it into print. I could keep tinkering away at this thing forever, of course: I’ve got to call it quits at some stage and that point has arrived. (It’s also in the contract.) I’m satisfied with it as is…When a publisher’s draft is ready, we’ll both get our own hard copies to mark up and return for the final print-ready version.

Translation: Paul has finished orchestrating The Letter and is ready to transmit the manuscript to Subito Music. Once it’s set up in type, we’ll proofread it, after which the orchestral score will go to press.

Paul was still tinkering with the score, as well as double-checking the edited text of my libretto, well into Sunday evening. At 10:13 he sent me this e-mail: “Why alter the second time the judge asks about the verdict and not the first time? I think they should be identical.”

Paul was still tinkering with the score, as well as double-checking the edited text of my libretto, well into Sunday evening. At 10:13 he sent me this e-mail: “Why alter the second time the judge asks about the verdict and not the first time? I think they should be identical.”

Translation: Leslie Crosbie goes on trial for murdering her lover toward the end of of The Letter. I originally had the judge singing “Gentlemen of the jury, have you reached your verdict?” before and after a hallucination scene in which Leslie imagines that the blood-spattered foreman of the jury is her dead lover. (I thought that up myself. Cool, huh?) Paul wanted to know whether a judge in British Malaya would have used the same language as an American judge, a question that threw me for a loop. Then I had a brainwave, went to Amazon, and searched the text of Agatha Christie’s Witness for the Prosecution, in which the judge says “Members of the jury, are you all agreed upon your verdict?” Operating on the assumption that Christie would have gotten that kind of detail right, I changed the libretto accordingly–but I forgot to fix the judge’s pre-hallucination speech! Fortunately, Paul caught my mistake, and now the judge sings the same words both times.

Half an hour ago Paul sent me eight Sibelius files marked FINAL, one for each scene of the opera. I’ll listen to them after I get back to New York. Right now, though, I plan to go downstairs to the pool of the Biltmore Hotel, where Mrs. T and I are staying in between seeing plays in south Florida, and take a celebratory swim. It’s seventy-eight degrees in Coral Gables, and I’m so sick and tired of blizzards, air travel, interstate highways, and looming deadlines that I feel like banging my head against the wall a couple of dozen times.

I think I deserve a break, don’t you?

TT: Coast to coast to coast (I)

DECEMBER 31 Mrs. T and I loaded our car late in the afternoon and drove through a slippery snowstorm from rural Connecticut to LaGuardia Airport, where we holed up in a just-adequate hotel. We were still quivering with retrospective anxiety as we fell into our rock-hard beds. No part of our four-hour journey was pleasant.

JANUARY 1 After breakfast we crossed the Grand Central Parkway, staggered onto a waiting plane, and embarked on the first leg of my first reviewing trip to Florida. I’ve never flown from New York City to Palm Beach in January (or at any other time, for that matter). It was an instructive experience. The temperature was 20 when we got on the plane and 71 when we got off it.

JANUARY 1 After breakfast we crossed the Grand Central Parkway, staggered onto a waiting plane, and embarked on the first leg of my first reviewing trip to Florida. I’ve never flown from New York City to Palm Beach in January (or at any other time, for that matter). It was an instructive experience. The temperature was 20 when we got on the plane and 71 when we got off it.

We spent the afternoon driving up and down Ocean Boulevard, the sometime home of Rod Stewart, whose hedges were pointed out to us by our host, a New York City Ballet dancer who hung up his slippers to become a dance photographer. We goggled at the villas and the view, noting the close resemblance of everything we saw to everything that Donald Westlake described in Flashfire, a Parker novel that takes place on Billionaires Row, the richest, snootiest part of Palm Beach.

After dinner we returned to our borrowed apartment on Ibis Isle, where I checked my e-mail and discovered that Westlake had died the night before. A line from Champagne for One, the Nero Wolfe novel that I was reading, popped into my mind: “In a world that operates largely at random, coincidences are to be expected, but any one of them must always be mistrusted.”

JANUARY 2 A late sleep, a late lunch, a leisurely walk on Midtown Beach (open to the public!), a drive across the Southern Boulevard Bridge to Palm Beach Dramaworks, where we saw Eugène Ionesco’s The Chairs in an eighty-four-seat theater, followed by a late supper around the corner at Forté di Asprinio, where the food and décor are soooo trendy but the staff is both friendly and obliging. Mrs. T took a bite of my pappardelle, which was very tasty, and announced that it was the first time she’d eaten rabbit. “No more bunnies for me,” she said firmly.

JANUARY 2 A late sleep, a late lunch, a leisurely walk on Midtown Beach (open to the public!), a drive across the Southern Boulevard Bridge to Palm Beach Dramaworks, where we saw Eugène Ionesco’s The Chairs in an eighty-four-seat theater, followed by a late supper around the corner at Forté di Asprinio, where the food and décor are soooo trendy but the staff is both friendly and obliging. Mrs. T took a bite of my pappardelle, which was very tasty, and announced that it was the first time she’d eaten rabbit. “No more bunnies for me,” she said firmly.

JANUARY 3 To Coral Gables by way of the Norton Museum of Art. One of the nice things about smallish regional museums is that they tend to have most of their best pieces on display, so we got to see Stuart Davis’ “New York Mural.” Davis is one of my favorite American painters–I own a copy of his last screenprint–and this canvas, painted in 1932, is a choice example of his mature style. Surrounding it were equally fine pieces by Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Charles Sheeler, and a gorgeous 1962 Richard Diebenkorn painting called “Mission Landscape” hung in the next gallery.

JANUARY 3 To Coral Gables by way of the Norton Museum of Art. One of the nice things about smallish regional museums is that they tend to have most of their best pieces on display, so we got to see Stuart Davis’ “New York Mural.” Davis is one of my favorite American painters–I own a copy of his last screenprint–and this canvas, painted in 1932, is a choice example of his mature style. Surrounding it were equally fine pieces by Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Charles Sheeler, and a gorgeous 1962 Richard Diebenkorn painting called “Mission Landscape” hung in the next gallery.

Our final destination was the palatial Biltmore Hotel, whose Web site discourses at length on its glory days:

In its heyday, this Miami luxury resort played host to royalty, both Europe’s and Hollywood’s. The hotel counted the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Ginger Rogers, Judy Garland, Bing Crosby, Al Capone and assorted Roosevelts and Vanderbilts as frequent guests. Fashion shows, gala balls, aquatic shows by the grand pool and weddings were de rigueur as were world class golf tournaments. A product of the Jazz Age, big bands entertained wealthy, well-traveled visitors to this American Riviera resort.

Today the Biltmore is, among other things, the home of GableStage, which is giving the regional premiere of Adding Machine, whose off-Broadway production I reviewed in The Wall Street Journal last February:

This Chicago-to-Off-Broadway transfer, adapted by Jason Loewith and Joshua Schmidt from the 1923 play, takes Elmer Rice’s once-iconic, now-forgotten story of a beaten-down bookkeeper who hates his wife and murders his boss and turns it into a one-act techno-minimalist opera of near-arrogant sophistication. Would that Mr. Schmidt’s score were as memorable as it is slick, but the small-scale production, directed with awesome self-assurance by David Cromer, is so effective that you almost forget how forgettable the music is. Every other piece of this brainy little show, from cast to sets to lighting, is as close to ideal as you can get. While I never quite managed to shake the impression that I was seeing a graduate project of genius rather than a fully mature work of art, don’t let that stop you from heading downtown to see “Adding Machine.” It may be heartless, but it’s the opposite of dull.

One of the frustrating aspects of my job as a drama critic (there aren’t many) is that I rarely get to see good shows twice. Even though I had my doubts about it, Adding Machine made so strong an impression on me that I wanted to see it again as soon as I possibly could, which was one of the reasons why I opted to spend the first part of January covering theater in Florida.

I was also amused by the contrast between the cultural reputation of south Florida, which isn’t exactly eggheady, and the decidedly intellectual tone of the three shows that I came here to see. You can’t get much more highbrow than The Chairs, Adding Machine, and Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa, which opens in Fort Myers on Friday.

(To be continued)

TT: Almanac

Here, in front of the summer hotel

the beach waits like an altar.

Anne Sexton, “The Kite”

TT: Donald E. Westlake, R.I.P.

I’ve praised Donald Westlake many times on this blog and elsewhere, so it will come as no surprise that the news of his unexpected death, which reached me in Florida via Sarah, hit me hard.

I’ve praised Donald Westlake many times on this blog and elsewhere, so it will come as no surprise that the news of his unexpected death, which reached me in Florida via Sarah, hit me hard.

Westlake was one of America’s great literary entertainers, both under his own name and as “Richard Stark,” the pseudonym that he used when writing about Parker, the quintessential noir anti-hero. As I wrote last May in praise of the Parker novels:

Anyone who doubts the existence of original sin, or something very much like it, would do well to reflect on the enduring popularity of the novels of Richard Stark. For forty-six years now, Stark has been writing terse, hard-nosed books about a cold-hearted burglar named Parker (nobody seems to know his first name) who steals for a living, usually gets away with it, and stops at nothing, including murder, in order to do so. I couldn’t begin to count the number of people Parker has killed in the course of the twenty-four books in which he figures. His only virtues are his intelligence and his professionalism–yet you end up rooting for him whenever you read about him. Nietzsche knew why: when you look into an abyss, the abyss looks into you….

It’s a permanent puzzlement that Westlake, who is best known for his charming comic crime novels, should also have dreamed up so comprehensively unfunny a character as Parker, which doubtless tells us something of interest about human dualism, the subject matter of all film noir and noir-style fiction. I wouldn’t care to speculate about what it is in Westlake’s psyche that makes him so good at writing about Parker, much less what it is that makes me like the Parker novels so much. Suffice it to say that Stark/Westlake is the cleanest of all noir novelists, a styleless stylist who gets to the point with stupendous economy, hustling you down the path of plot so briskly that you have to read his books a second time to appreciate the elegance and sober wit with which they are written.

The University of Chicago Press recently embarked on a uniform edition of the Parker novels. Westlake wrote many other good things–above all the long series of wonderfully funny novels about John Dortmunder, Parker’s comic alter ego, that he published under his own name–but I expect that it is Parker for which he will be best remembered, and rightly so.

The New York Times obituary is here.

UPDATE: Go here to read a lengthy and informed tribute by Ethan Iverson of the Bad Plus, who got to know Westlake toward the end of his life.

TT: The best of the best

I have a piece in the current issue of Commentary called “My Favorite Classical Recordings.” It’s an annotated list of twenty-five recordings made between 1926 and 1973 that I regard as indispensable:

None of the records on this list is new. I have been listening to most of them for a quarter-century or more, and to some since I was a boy. They have withstood the test of time and hard usage. Beyond choosing only performances that are currently in print, I have made no effort to balance the list in any way, and for that reason some of the composers, performers, and pieces that I love best are not represented on it. It is nothing more–or less–than a roll of personal favorites, the 25 classical recordings that have given me special pleasure throughout a lifetime of listening. Perhaps some of them will do the same for you….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: The luck of the Irish

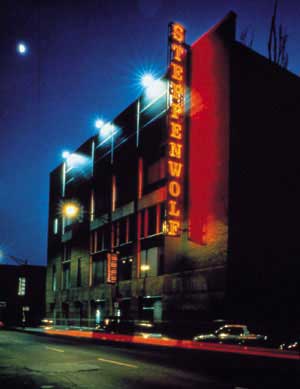

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I review two Irish plays, one in Chicago (Steppenwolf’s production of Conor McPherson’s The Seafarer) and one off Broadway (the Atlantic Theater Company’s revival of Martin McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan). Both are superlative. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“The Seafarer” was seen on Broadway last season in a production that was staged in exemplary fashion by the author himself. On that occasion I described it as “worthy of comparison with the finest work of the young Brian Friel.” For an Irish playwright, that’s a 150-proof compliment. But first impressions can be deceptive, so when Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater Company announced that it was mounting a new production, I changed my holiday travel schedule so that I could catch a performance in between flights, then drove through a snowstorm to find out whether “The Seafarer” was as good as I’d thought. Neither play nor production disappointed me. Anyone who’s seen Tracy Letts’ “August: Osage County” on Broadway knows what Steppenwolf can do, and they’ve done it again with “The Seafarer.” Randall Arney’s staging is decidedly different in tone from the Broadway production–among other things, he’s soft-pedaled the broad physical comedy that was a highlight of Mr. McPherson’s version–but equally effective in its quieter, less overtly Irish way….

“The Seafarer” was seen on Broadway last season in a production that was staged in exemplary fashion by the author himself. On that occasion I described it as “worthy of comparison with the finest work of the young Brian Friel.” For an Irish playwright, that’s a 150-proof compliment. But first impressions can be deceptive, so when Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater Company announced that it was mounting a new production, I changed my holiday travel schedule so that I could catch a performance in between flights, then drove through a snowstorm to find out whether “The Seafarer” was as good as I’d thought. Neither play nor production disappointed me. Anyone who’s seen Tracy Letts’ “August: Osage County” on Broadway knows what Steppenwolf can do, and they’ve done it again with “The Seafarer.” Randall Arney’s staging is decidedly different in tone from the Broadway production–among other things, he’s soft-pedaled the broad physical comedy that was a highlight of Mr. McPherson’s version–but equally effective in its quieter, less overtly Irish way….

“The Cripple of Inishmaan” is a snarlingly black comedy whose subject is stage-Irishness, the smotheringly quaint charm that continues to be used, in Ireland and elsewhere, to paper over the harsh realities of village life. The island community of Inishmaan is an echo chamber in which everybody knows everybody else’s business and gossips about it ceaselessly and circularly: “I do worry awful about Billy when he’s late in returning, d’you know?” “Already once you’ve said that sentence.” To live in so narrow a place is agony to Billy (Aaron Monaghan), the title character, an orphan who longs with all his heart to break away and seek a wider, warmer world. The genius of “The Cripple of Inishmaan” is that it plays Billy’s plight for laughs, steering away from sentimentality and forcing the viewer to look squarely upon the ordinary sorrows of his daily life.

Unlike Steppenwolf’s production of “The Seafarer,” this revival is an all-Irish import. It was originally staged by Garry Hynes for the Druid Theater Company and features the same actors who were seen in Galway. I can’t imagine a more knowing performance…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.