“Men reject their prophets and slay them, but they love their martyrs and honor those they have slain.”

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (trans. Constance Garnett)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“Men reject their prophets and slay them, but they love their martyrs and honor those they have slain.”

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (trans. Constance Garnett)

* * *

Yet another new jukebox biomusical, “Tina: The Tina Turner Musical,” has opened on Broadway, and it’s not awful, not even close. In fact, some parts of the show, in which Adrienne Warren impersonates the washed-up R&B singer who dumped her wife-beating spouse (Daniel J. Watts) and transformed herself into a glitzed-up rocker at the venerable age of 45, are genuinely entertaining. Nevertheless, I’m afraid—very, very afraid—that “Tina” will be a hit….

The jukebox biomusical, in which the smoothed-over story of a pop star’s life is turned into the plot of a musical whose score consists of that star’s hit records, is an uncreative bastard genre that has done much damage to Broadway. The rising popularity of jukebox shows is choking the life out of the traditional musical in much the same way that the success of comic-book franchise movies has all but killed off the adult-friendly films that used to dominate America’s multiplexes. Every time a jukebox show rings the box-office gong and moves into a New York theater for a long, profitable run, it becomes that much harder for a better show with new songs and a fresh plot to carve out a place on Broadway. Why should a theatrical producer bet on a necessarily risky musical like, say, “The Band’s Visit” or “Hadestown” when she could be backing “Beautiful: The Carole King Musical” instead?…

“Cyrano,” Erica Schmidt’s new off-Broadway musical version of Edmond Rostand’s “Cyrano de Bergerac,” is half of a great small-scale musical, performed and produced with such flair that you’ll be tempted—up to a point—to forgive its fatal flaw.

Ms. Schmidt, who doubles as the show’s director, has given us a warm-hearted, unselfconsciously romantic prose rendering of the oft-told tale of the idealistic soldier-poet with a very long nose (Peter Dinklage) who lacks the courage to declare his unrequited love for the beauteous Roxanne (Jasmine Cephas Jones). Mr. Dinklage, a superlatively gifted four-foot-four character actor with a gorgeous bass-baritone voice who was catapulted into stardom by his eight-season stint on “Game of Thrones,” is close to ideal as Cyrano…

All of which brings us to the score, which is the work of The National, an indie band whose Philip Glass-flavored art-rock songs are hugely and deservedly popular with millennial listeners. Alas, they haven’t a clue as to how show tunes work…

* * *

To read my Tina review, go here. To read my Cyrano review, go here.The trailer for Tina:

Peter Dinklage talks about Cyrano:

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I explain how American theaters rarely perform older plays—and what effect that has on our theatrical culture. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

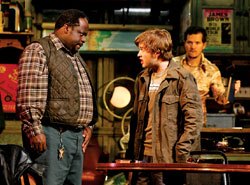

The most revealing news of the 2019-20 theatrical season was the announcement last month of a pair of big-ticket revivals, Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and David Mamet’s “American Buffalo,” both of which are set to open on Broadway next April. What made it so noteworthy is that “Virginia Woolf,” first performed in 1962, has already been done there four times, most recently in 2012-13, while “American Buffalo,” first performed in 1975, has been done three times, most recently in 2008.

Why do these two well-worn plays get revived so often—and why are they coming back to Broadway so soon? Three interlocking reasons come to mind:

• Unlike most older American plays, they’re small-cast one-set shows (“Virginia Woolf” calls for four actors, “American Buffalo” for four) that can be produced cheaply.

• They contain flashy roles irresistible to well-known male actors looking for a challenge (“American Buffalo” will star Sam Rockwell, “Virginia Woolf” Rupert Everett).

• They’re known by name to everyone who knows anything about 20th-century theater, in part because both plays were filmed to outstanding effect.

Above all, though, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and “American Buffalo” are full-fledged American classics—and if you define an “American classic” as a great play that is revived with reasonable regularity, then only a small number of 20th-century plays fill that bill. But that’s not because of a shortage of great modern plays: It’s because our theaters tend not to revive older plays, classic or otherwise

* * *

Read the whole thing here.A scene from the 2012 Broadway revival of Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (as previously mounted at Washington’s Arena Stage). Tracy Letts and Amy Morton play George and Martha:

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

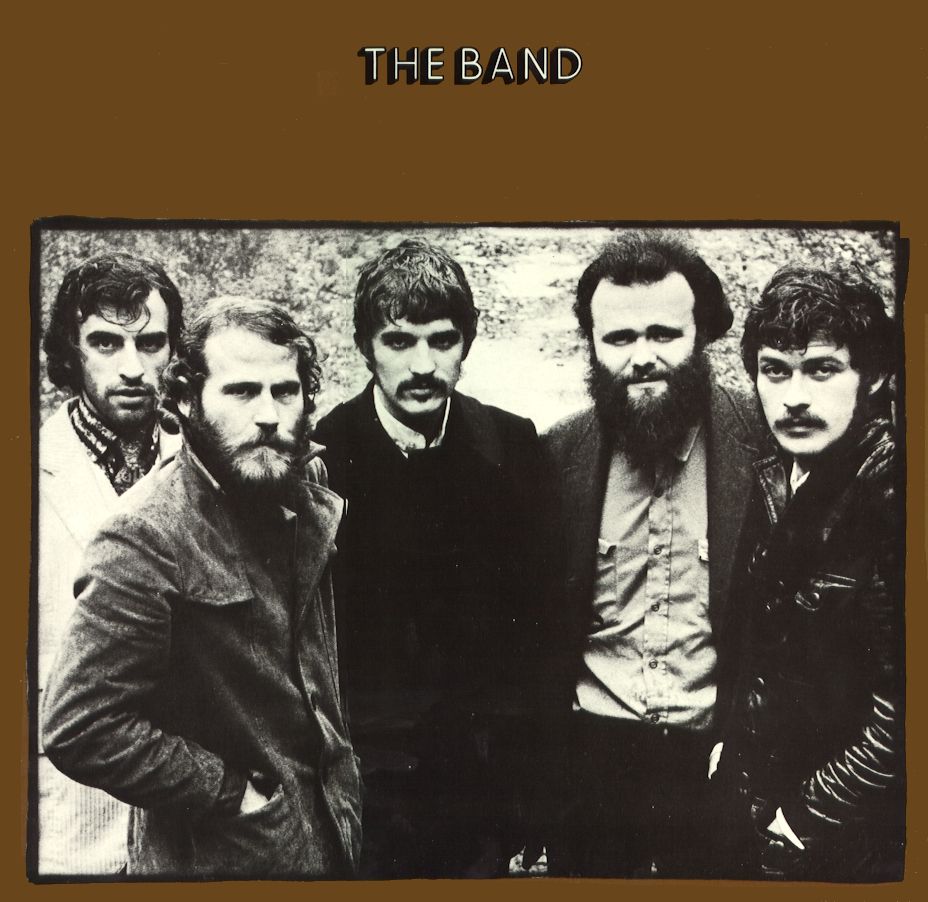

Popularly known to rock aficionados as the “brown album,” The Band is, in my firmly held opinion, the best rock-and-roll record ever made and one of the best pop records of any kind, a work of creative genius in which rock, country, and folk are blended together into an indissoluble amalgam for which the term “Americana” might have been coined. What pop music should be, it is.

The Band was reviewed in Rolling Stone by Ralph J. Gleason, who is now mainly remembered as a jazz journalist but was no less interested in other kinds of pop music, and whose 1969 review, which I read in book form two years after the fact, made me go right out and buy that extraordinary record. I can’t remember having read a review that conveyed more clearly in words alone the essential quality of a work of musical art:

I hear these songs as a sound track to James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, to the real documentary of the American truth. They are sparse songs with never a superfluous note or an unnecessary syllable. And yet the sparseness, like a Picasso line, is so right that it implies everything needed. Lean and dusty, perhaps, like Henry Fonda walking down the road at the beginning of Grapes of Wrath, it says volumes in a phrase…

With their flashing images of the American continental landscape…they speak for the continent in “King Harvest (Has Surely Come).” They could have called the album America, Robbie says, and after you play it a few times you know what he means. We live in these cities and we forget that there is more than 3000 miles between New York and the smog of Los Angeles and those 3000 miles are deeply rooted to another world in another time and with another set of values. “King Harvest” takes us there.

The hymn-like quality of the voicings, the use of counterpoint and contrapuntal rhythms by the singers, the weaving of the voices in and out into a pattern that grows each time you hear it, are the things that make the sound of this music so compelling. In “King Harvest,” as in other songs, individual sections with contrasting timbres, moods, rhythms and sounds are juxtaposed to make a totality that is so open it can cover whatever you feel. The sense of doom, almost Biblical in its prophetic warning, of “Look Out Cleveland” is unique in contemporary popular song, so far removed from the obvious morbidity of some of the songs of past years as to be an adult to their child. (This music, of course, is mature, made by men who know who they are and what they want to do. Its appeal to the teenybopper Top 40 audience seems, on the evidence, to be limited.)

Maybe so, but the appeal of The Band to my fifteen-year-old small-town self was overwhelming. I wouldn’t have put it this way back then, but it was the first pop album I’d heard that spoke to me with the same profundity and complexity as did the best jazz and classical music—and if I’d known anything about country, I would have known that it is also as true to the pain and uncertainty of adult life as any of the songs of Hank Williams or Bill Monroe. Gleason nailed it: The Band is mature music.

In retrospect, I simply can’t understand why such a record hit me where I lived. I was anything but mature in 1971. Yet I have no doubt that it did so, especially “King Harvest (Has Surely Come),” an unsentimentally told tale of the suffering and courage of a southern farmer which made me weep then and does so today. After listening to it for a half-century, I can say with the absolute assurance that only the passage of time can give that “King Harvest” is a truly great work of popular art, a miniature masterpiece that is directly comparable in quality to, say, Frank Sinatra’s “One for My Baby,” George Jones’ “The Grand Tour,” Skip James’ “Devil Got My Woman,” or Charlie Parker’s “Parker’s Mood.” (Or Schubert’s “Wanderers Nachtlied II,” for that matter.) Having once heard it, I knew what popular music at its very best was capable of saying about human experience, and have never again gladly settled for anything less.

(To be continued)

* * *

The Band plays “King Harvest (Has Surely Come),” from The Band, recorded in 1969. The members of the group are Rick Danko on bass, Levon Helm on drums, Garth Hudson on organ, Richard Manuel on piano and lead vocals, and Robbie Robertson on guitar. (On this track, John Simon also plays electric piano.) The song is by Robertson:

The Band rehearses “King Harvest” at Robbie Robertson’s studio in Woodstock, N.Y., in 1969:

To hear me talk in detail about The Band with Scot Bertram and Jeff Blehar in 2018, go here.* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.

To read about album #14, go here.

To read about album #15, go here.

To read about album #16, go here.

To read about album #17, go here.

To read about album #18, go here.

Buddy Rich appears with his band on a 1967 episode of The Mike Douglas Show:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“Injustice is relatively easy to bear; what stings is justice.”

H.L. Mencken, “Footnote on Criticism”

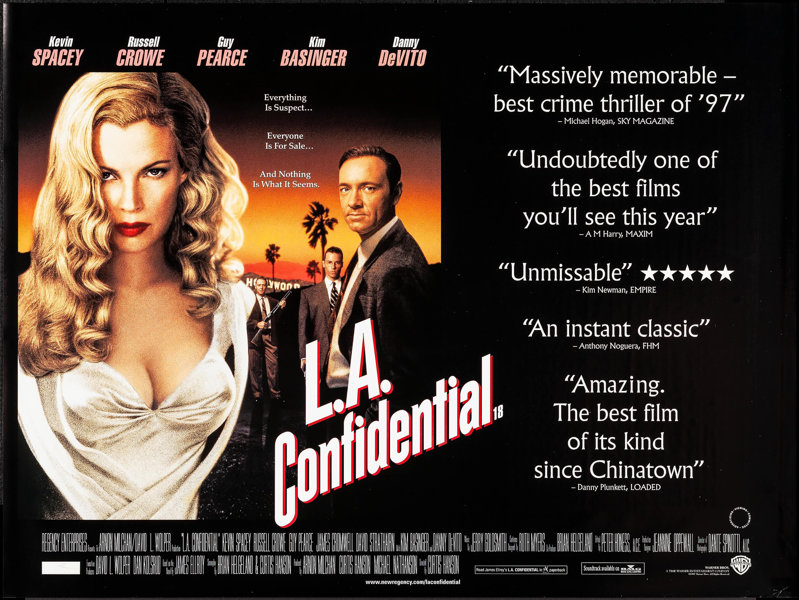

Titus Techera, who hosts a podcast for the American Cinema Foundation on which he and his guests discuss important films of the past and present, invited me back for the latest in a series of conversations about film noir and “noir-adjacent” films.

In the latest episode, we discuss Curtis Hanson’s L.A. Confidential, written by Hanson and Brian Helgeland, scored by Jerry Goldsmith, and starring Russell Crowe, Guy Pearce, Kevin Spacey, Kim Basinger, and James Cromwell. Our hour-long conversation is now available on line.

Here’s Titus’ summary of our conversation:

To listen to or download this episode, go here.We have a reversal of the noir—the femme fatale helps redeem rather than damn protagonists who were corrupt before they came to make a serious moral decision. Curtis Hanson’s movie makes for a revision of heroism away from noir’s tragic destiny toward American drama, where happy ends are possible, in limited ways, for some of the people who deserve them.

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

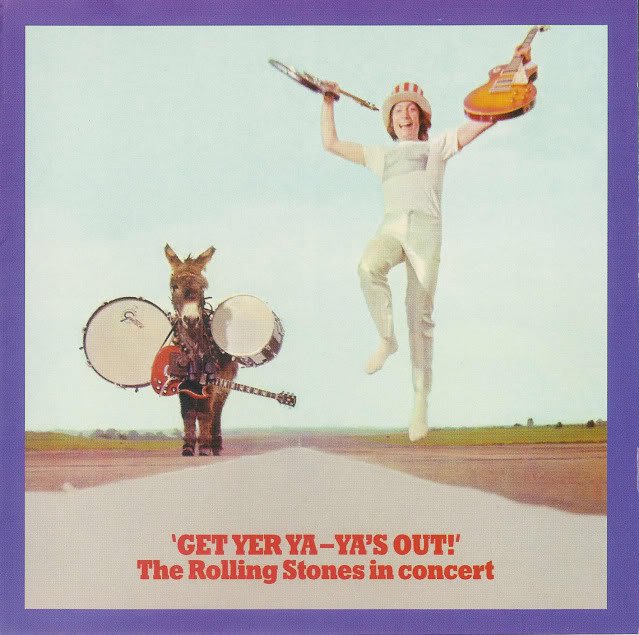

It happens that I’ve never bought a copy of Rolling Stone. It wasn’t sold at any of the newsstands in or near Smalltown, U.S.A., when I was growing up. I did, however, profit from its exceptionally well-written record reviews, at least the ones that made it into The Rolling Stone Record Review, a mass-market paperback that came out in 1971. I bought The Rolling Stone Record Review not long after it was published and read it until the glue dried up and the pages fell out, something that had never before happened to me. Not at all surprisingly, it exerted a powerful and continuing influence on me for many years thereafter.

As I wrote in this space back in 2015:

Some of the reviews reprinted therein were so strikingly written that I can still quote them…It was my Bible of hipness, a vade mecum of all that was most serious about rock, and it was a long time before I dared to break away from its seemingly apodictic judgments and start trusting my own ears.

Ya-Ya’s, “Midnight Rambler” in particular, changed my tune. It was right around the time that I bought that explosive album that my father generously bought me a Fender bass and a Bassman 10 amplifier. Whenever the house was empty, I plugged it in, cranked the volume up to eleven and played along with the Stones. On one never-to-be-forgotten occasion, I played so loud that the bathroom cabinet popped open and its contents fell into the sink.

I now prefer other kinds of rock, including the Stones’ studio albums from the same period and (sorry, Lester) Live at Leeds. But I still think that Ya-Ya’s is a pretty damn wonderful record, raunchy and fierce to a fault, and I will always be indebted to Lester Bangs and The Rolling Stone Record Review for inspiring me to buy it.

(To be continued)

* * *

From Get Your Ya-Ya’s Out, the Rolling Stones play “Midnight Rambler” at Madison Square Garden in 1969. The band consists of Mick Jagger on lead vocals and harmonica, Keith Richards and Mick Taylor on guitar, Bill Wyman on bass, and Charlie Watts on drums:

A filmed performance of the same song, played live at London’s Marquee Club two years later:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.

To read about album #13, go here.

To read about album #14, go here.

To read about album #15, go here.

To read about album #16, go here.

To read about album #17, go here.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

An ArtsJournal Blog