Joe Louis is the guest on This Is Your Life, hosted by Ralph Edwards and originally telecast by NBC in 1961:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Joe Louis is the guest on This Is Your Life, hosted by Ralph Edwards and originally telecast by NBC in 1961:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“Merriment is always the effect of a sudden impression. The jest which is expected is already destroyed.”

Samuel Johnson, The Idler (May 26, 1759)

* * *

Old-fashioned stage comedy is in short supply on Broadway, for the good reason that comic tastes in the U.S. have changed. We no longer have a Neil Simon because we no longer need a Neil Simon, a purveyor of joke-slinging stage sitcoms for suburbanites. Mr. Simon’s place in the theatrical universe was long ago taken over by network TV. (Why, then, don’t we have an Alan Ayckbourn? Because England’s funniest playwright specializes in a uniquely English brand of farce, the sad comedy of middle-class manners…but that’s a different piece.) Yet we still feel the need to laugh when we go to the theater, perhaps more so than ever before. Hence the warm response to James Graham’s “Ink,” Tracy Letts’ “Linda Vista” and Theresa Rebeck’s “Seared,” all of which were really, really funny—as well as to Bess Wohl’s “Grand Horizons,” which is, by contrast, only just funny enough.

To be sure, “Grand Horizons” has a promising setting, the cookie-cutter apartment of Nancy and Bill French (Jane Alexander and James Cromwell), an octogenarian couple who live in “a private home in an independent living community for seniors.” (You know where you are because there are red panic buttons and easy-to-spot grab bars close to every door.) Such communities are new to American theater. What is life like for their residents? What do they do with themselves all day long, and how do they feel about it? The answers to these questions could be the stuff of an interesting play, but Ms. Wohl doesn’t even try to deliver the goods, choosing instead to start the show by setting off an old-fashioned comic firecracker. Nancy and Bill sit down to dinner. “I think I would like a divorce,” she tells him. “All right,” he replies. Blackout….

Unfortunately, what follows is a string of missed comic opportunities….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.A video featurette about Grand Horizons:

Martyn Green sings “My Name Is John Wellington Wells,” a patter song from Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Sorcerer. This performance was originally telecast as part of an episode of Omnibus, which aired on CBS on January 16, 1955. The host is Alistair Cooke:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“Anything invented after you’re 35 is against the natural order of things.”

Douglas Adams, The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time

Buying art from Italy turns out to be a horrifically complicated business, so much so that it took nearly four months for me to untie all of the requisite bureaucratic red tape. But I sliced through the final Gordian knot a couple of weeks ago, and “Composition (1961)” arrived by overseas courier yesterday, just in time to console me for not having been able to see “Hans Hofmann: The Nature of Abstraction” in Massachusetts. It is what print collectors call a “rich impression,” one whose illusion of depth is so powerful that I gasped when I took it out of the package and saw it “in the flesh” for the very first time.

It happens that Mrs. T doesn’t much care for “Woman’s Head,” the Hofmann that I bought back in 2005, just before we met, which hangs over our living-room couch alongside equally striking prints by Milton Avery, Richard Diebenkorn, John Marin, and Joan Mitchell. I’m guessing, however, that “Composition (1961)” will fit neatly into the space previously occupied by “Woman’s Head,” and my plan is to hang it as soon as it comes back from our trusty framer. First, though, I’ll bring it to New York-Presbyterian so that she can get a look at the latest addition to the Teachout Museum, which is small enough for me to tuck under one arm. She hasn’t seen any art since entering the hospital in December, and my hope is that it’ll brighten her life to hold “Composition (1961)” in her hands and imagine how it will look over the couch.

That’s another joy of collecting art: sometimes you can take it with you.

UPDATE: Here’s how it looks on the wall.

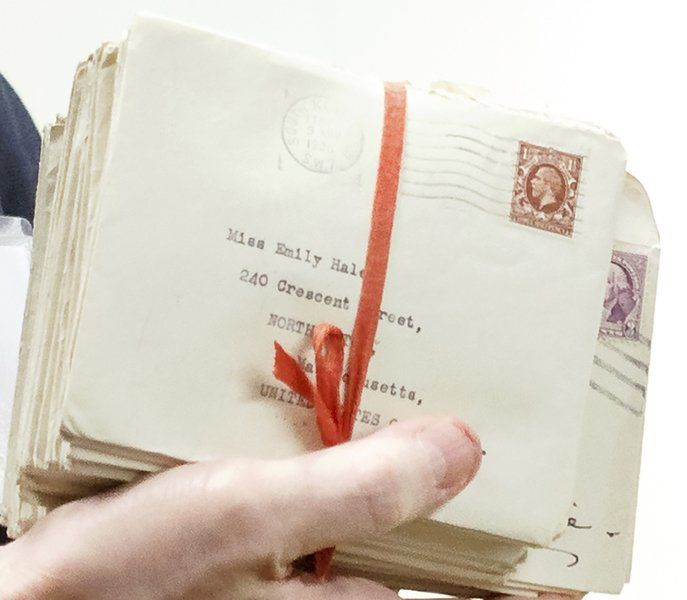

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, occasioned by the unsealing of a crate of love letters sent by T.S. Eliot to Emily Mann, I write about artists who have sought to use posthumous publication to shape the way they are viewed by posterity—sometimes successfully, sometimes not. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Earlier this month, the contents of a crate of love letters written by the most famous poet of the 20th century and sealed for the past half-century were finally made available to researchers by Princeton University. The crate contained 1,131 letters sent by T.S. Eliot to Emily Hale, the woman whom the author of “The Waste Land” was long thought to have loved prior to and during his marriage to Vivienne Haigh-Wood, which ended when Haigh-Wood died in a mental hospital in 1947. Simultaneous with the opening of the letters, which were left by Hale to Princeton on condition that they not be made available for public viewing until 50 years after she and Eliot had died, Eliot’s estate released a frigid letter in which he sniffily informed posterity that Hale had neither loved nor had “sexual relations” with him. Moreover, he added, she was “not a lover of poetry” and “was not much interested in my poetry,” claiming that she “would have killed the poet in me” had they married after Haigh-Wood’s death.

As literary time bombs go, Eliot’s letter, which he wrote specifically to be opened when and if Hale’s letters became public, is more than a little bit catty. But his determination to put Hale in what he took to be her place is hardly unprecedented. Artists of all kinds have gone to considerable trouble to sound off from beyond the grave. H.L. Mencken, for example, left behind a stack of autobiographical manuscripts, including a 2,100-page diary and a pair of book-length memoirs, “My Life as Author and Editor” and “Thirty-Five Years of Newspaper Work,” that he bequeathed to Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library and placed under a 35-year time seal at the time of his death in 1956. Published between 1989 and 1994, these works amounted to an extended attempt by Mencken (in his words) to rewrite “the literary history of the United States in my time,” depicting such celebrated contemporaries as Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sinclair Lewis “precisely as I saw them.”….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.“The real problem is not whether machines think but whether men do.”

B.F. Skinner, Contingencies of Reinforcement

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

An ArtsJournal Blog