“You are a senior executive of a big company and you know the first rule: authority and responsibility must be congruent and commensurate to each other. If you don’t want authority and shouldn’t have it, don’t talk about responsibility. And if you don’t want responsibility and shouldn’t have it, don’t talk about authority.”

Alfred P. Sloan (quoted in Peter F. Drucker, Adventures of a Bystander)The twenty-five record albums that changed my life (6)

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums every weekday in the order in which I first heard them.

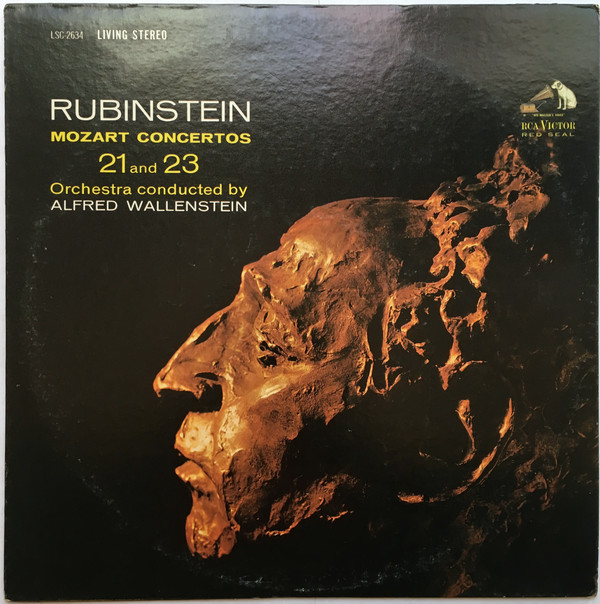

It scarcely seems possible, but I’ve been listening to this album, which introduced me to the music of Mozart, for fifty years. I bought it when I was thirteen, the same age as Arthur Rubinstein when he made his Berlin debut playing Mozart’s A Major Piano Concerto with an orchestra led by Joseph Joachim, his patron and Brahms’ intimate friend, in 1900. “He who can play Mozart so successfully is a chosen one among the elect,” one of the critics wrote, a sentence which the youngster got by heart and remembered for the rest of his long life.

Rubinstein adored Mozart’s music, but he rarely played it in public. Even so, he had a special affection for the divine simplicity of this particular piece, which he recorded three different times, in 1931, 1946, and 1962. This is the last of them, and while it is no longer my favorite recording—I’ve come to find his Mozart playing a bit on the pale side—I still love it, undoubtedly for sentimental reasons, which is just fine by me.

To discover Mozart is by definition a key moment in every musician’s life, he being the master of masters. So far as I know, the only artist of note who had a bad word to say about him was Noël Coward, who claimed that his operas sounded like “piddling on flannel.” Though it’s a funny line, my own feelings are more aptly summed up by Aaron Copland, himself a great composer, in a 1956 essay that I can do no better than quote in extenso:

It would be futile to try to single out any one work as my favorite, but the slow movement of this concerto is as good a pick as any. Each bar is suffused with a desperate, heart-tearing melancholy, yet Mozart never exaggerates his unappeasable sorrow: he is content merely to show it to you, in much the same way that Cézanne shows you the garden at Les Lauves, his country home, leaving the rest to your imagination.Paul Valéry once wrote: “The definition of beauty is easy: it is that which makes us despair.” On reading that phrase, I immediately thought of Mozart. Admittedly, despair is an unusual word to couple with the Viennese master’s music. And yet, isn’t it true that any incommensurable thing sets up within us a kind of despair? There is no way to seize the Mozart music. This is true even for a fellow-composer, any composer—who, bring a composer, rightfully feels a special sense of kinship, even a happy familiarity, with the hero of Salzburg. After all, we can pore over him, dissect him, marvel or carp at him. But in the end there remains something that will not be seized. That is why, each time a Mozart work begins—I am thinking of the finest examples now—we composers listen with a certain awe and wonder, not unmixed with despair. The wonder we share with everyone; the despaire comes from the realization that only this one man at this one moment in musical history could have created works that seem so effortless and so close to perfection.

(To be continued)

* * *

Maurizio Pollini plays Mozart’s A Major Piano Concerto, K. 488, accompanied by Karl Böhm and the Vienna Philharmonic. This performance was filmed in 1976:

Arthur Rubinstein plays the piano and talks about music in The Love of Life, an Oscar-winning 1969 documentary:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

Lookback: the (unrealized) promise of film criticism

From 2009:

Read the whole thing here.Film was the master medium of the twentieth century. Within a few years of its invention, it had supplanted live theater and the novel as the main way in which most people experienced the art of storytelling, and it retains its cultural dominance to this day (though only if you count TV as a species of filmmaking, which you should). It follows, then, that film criticism should by definition be worth reading. Right? Er, well, sometimes. Most of it is in fact flaming hogwash…

Almanac: Peter Drucker on learning from other people’s mistakes

“Don’t ever try to learn from other people’s mistakes. Learn what other people do right.”

An unknown first-century rabbi (quoted in Peter F. Drucker, Adventures of a Bystander)

The twenty-five record albums that changed my life (5)

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums every weekday in the order in which I first heard them.

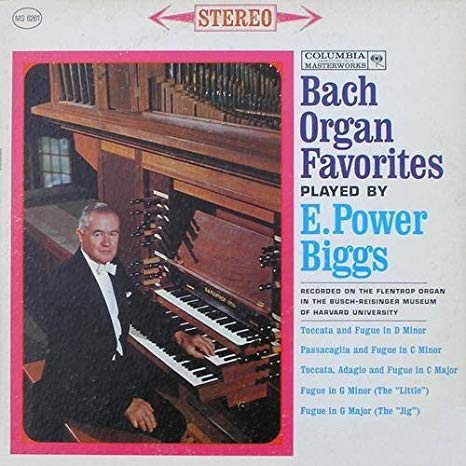

In those days, Biggs was probably the world’s most famous classical organist, but I didn’t know who he was, nor had I seen Walt Disney’s Fantasia, in which Leopold Stokowski’s Technicolor orchestral version of the D Minor Toccata and Fugue figures prominently. What first got me interested in Bach was “Bach Transmogrified,” one of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic, which aired in April of 1969. Switched-On Bach, the album on which Wendy Carlos (then known as Walter) performed an assortment of pieces by Bach on the then-new Moog Synthesizer, had just been released, and Bernstein took advantage of its popularity to present a TV concert in which he showed how Bach’s music could be played in a variety of ways. The program opened with the G Minor Fugue played by Michael Korn on Avery Fisher Hall’s pipe organ. Then Stokowski himself led the New York Philharmonic in his own resplendent orchestral transcription of the same piece, followed by an all-electronic synthesizer “performance.”

I was naturally fascinated by what Bernstein had to say, but it was the music, the G Minor Fugue in particular, that seized and held my attention. I went to Keith Collins Piano Company, Smalltown’s local music store, the very next day, hoping against hope to find a recording of that miraculous piece. Sure enough, they had Biggs’ Bach Organ Favorites in stock, and I brought the album home with delight and listened to it in ecstasy. I’ve been listening to it ever since.

(To be continued)

* * *

“Bach Transmogrified,” a Young People’s Concert by Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, originally telecast by CBS on April 27, 1969:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

Just because: a 1970 visit to Shelly’s Manne-Hole

“Jazz on Stage,” an episode from a 1970 syndicated TV series. This episode was directed by Jack Lewerke and filmed during a performance at Shelly’s Manne-Hole, a Los Angeles night club owned and run by Shelly Manne. The band consists of Bob Cooper on tenor saxophone, Hampton Hawes on piano, Ray Brown on bass, and Manne on drums:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

Almanac: Eugenie Schwarzwald on unprincipled “principles”

“I have no use for principles which demand human sacrifice.”

Eugenie Schwarzwald (quoted in Peter F. Drucker, Adventures of a Bystander)The twenty-five record albums that changed my life (4)

Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the order in which I first heard them.

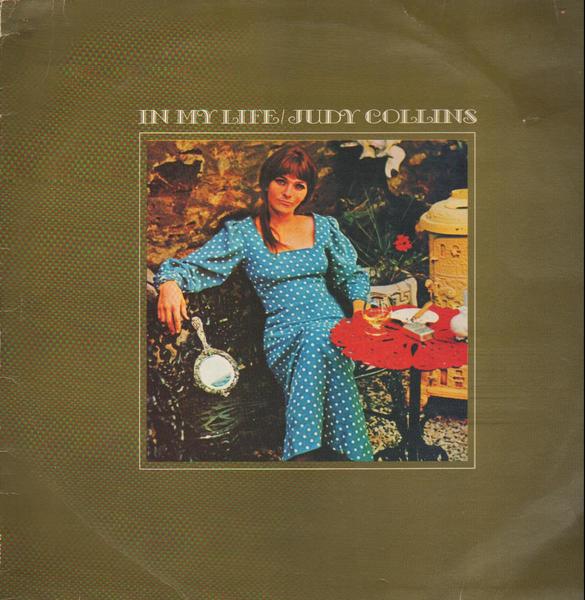

Not only does In My Life sound different from anything that Collins and her fellow folksingers had previously recorded, but it contains an unusually wide-ranging and imaginatively chosen assortment of material. In addition to the title track, a Lennon-McCartney ballad that first appeared on Rubber Soul, it includes, among other things, Leonard Cohen’s “Dress Rehearsal Rag” and “Suzanne,” Donovan’s “Sunny Goodge Street,” Dylan’s “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” Richard Fariña’s “Hard Lovin’ Loser,” Randy Newman’s “I Think It’s Going to Rain Today,” and Kurt Weill’s “Pirate Jenny” (from The Threepenny Opera, performed by Collins in Marc Blitzstein’s English-language version of Bertolt Brecht’s German lyric). Pop songs didn’t get much better than that in 1966, and Collins sang them all with her usual grace and delicacy.

Nowadays I (mostly) prefer the harder-edged original versions of the songs on In My Life, but Collins’ gentle lyricism was perfectly in tune with the inchoate longings of a painfully shy thirteen-year-old boy who had only just started to notice and be excited by the mysterious differences between men and women. Not surprisingly, I fell hopelessly in love with singer and songs alike, “Suzanne” in particular, and I would listen to In My Life countless times before moving away from Smalltown, U.S.A., and moving on to grittier musical fare.

(To be continued)

* * *

Judy Collins, introduced by Tommy Smothers, performs “I Think It’s Going to Rain Today” on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967. She is lip-synching to the orchestral accompaniment from In My Life:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

Replay: José Iturbi plays Liszt

José Iturbi plays Liszt’s Eleventh Hungarian Rhapsody in a 1940 film:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

Almanac: Arturo Toscanini on the tragedy of the great performer

“No true musician can be satisfied with his performance, even through an audience is driven to a frenzy.”

Arturo Toscanini (quoted by Halina Rodzinski in Our Two Lives)