In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the premiere of David Lindsay-Abaire’s Good People, which I didn’t like at all. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“Good People” is, or purports to be, a study of life in Southie, a down-at-heel Boston neighborhood beloved of movie stars who think they can do the local accent. Mr. Lindsay-Abaire, who comes from a real-life Southie family, managed to land a scholarship to a tony New England prep school, which was his escalator to fame and fortune. All this undoubtedly explains the plot of “Good People,” in which Margie (Frances McDormand, who works the charm pedal a bit too enthusiastically) is fired from her job as a clerk at a local dollar store, thus making it impossible for her to support her adult daughter, who was born prematurely and is severely handicapped (and who is kept offstage throughout the play, presumably so as not to shock the matinée crowd). In desperation, Margie looks up Mikey (Tate Donovan), an old high-school boyfriend who studied hard, became a doctor and now lives in a big house in a fancy suburb with his cute young wife (Renée Elise Goldsberry), who is–wait for it–an upper-middle-class black.

In the first scene, we see Margie being canned for chronic lateness. Needless to say, it’s not her fault: She has babysitter problems. Indeed, her only flaw is an endearing one, which is that she can’t stop herself from saying what she thinks at any given moment, no matter how ill-timed it may be. Otherwise, she’s a basically good person, and that brings us to the moral of the play, which is that bad things happen to good people–and vice versa. Take Mikey, who believes that his success is his own doing and not a matter of luck, a conviction that has made him resentful and guilt-ridden, two qualities that manifest themselves in his willingness to treat Margie like dirt.

In the first scene, we see Margie being canned for chronic lateness. Needless to say, it’s not her fault: She has babysitter problems. Indeed, her only flaw is an endearing one, which is that she can’t stop herself from saying what she thinks at any given moment, no matter how ill-timed it may be. Otherwise, she’s a basically good person, and that brings us to the moral of the play, which is that bad things happen to good people–and vice versa. Take Mikey, who believes that his success is his own doing and not a matter of luck, a conviction that has made him resentful and guilt-ridden, two qualities that manifest themselves in his willingness to treat Margie like dirt.

Herein lies part of the phoniness of “Good People.” Of course people like Margie and Mikey exist, but I doubt it’s a coincidence that they are exactly the kinds of people who fit into the familiar sociological narrative that permeates every page of this play. In Mr. Lindsay-Abaire’s America, success is purely a matter of luck, and virtue inheres solely in those who are luckless. So what if Mikey worked hard? Why should anybody deserve any credit for working hard? Hence the crude deck-stacking built into the script of “Good People,” in which Mikey is the callous villain who forgot where he came from and Margie the plucky Southie gal who may be the least little bit racist (though she never says anything nasty to Mikey’s wife–that would be going too far!) but is otherwise a perfect heroine-victim.

No less phony, though, is the fact that “Good People” plays like a comedy, not a tragedy. For all their grinding poverty, Margie and her Southie friends are incapable of uttering two consecutive lines without tossing in a snappy comeback….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Turn on, tune in, get serious

In my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal, I take note of a very important pair of high-culture home video releases, Leonard Bernstein: Omnibus and John Gielgud: Ages of Man. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

In the fledgling years of network TV, Sunday mornings and afternoons were reserved for serious news shows like Edward R. Murrow’s “See It Now” and high-culture programs of various kinds, a practice so universally accepted that those time slots were collectively known to grumbling journalists as the “cultural ghetto.” Little did the grumblers know that a half-century later, the fine arts would have all but vanished from the commercial networks–and would be increasingly hard to find on PBS, the non-commercial network that was originally founded in part to give high culture a safe haven.

I cut my artistic teeth watching TV on Sundays, and now that some of the long-lost programs of my youth have finally made their way to DVD, I find myself astonished by what ABC, CBS and NBC were willing to telecast all those years ago. For those who know PBS as the home of Lawrence Welk reruns and A&E as the network of “Dog the Bounty Hunter,” I recommend a pair of releases from E1 Home Video, “Leonard Bernstein: Omnibus” and “John Gielgud: Ages of Man.” Between them, they’ll open your eyes to the unlimited possibilities of TV as a force for cultural good–and fill you with despair at the fact that such high-minded programming has largely disappeared from the small screen.

I cut my artistic teeth watching TV on Sundays, and now that some of the long-lost programs of my youth have finally made their way to DVD, I find myself astonished by what ABC, CBS and NBC were willing to telecast all those years ago. For those who know PBS as the home of Lawrence Welk reruns and A&E as the network of “Dog the Bounty Hunter,” I recommend a pair of releases from E1 Home Video, “Leonard Bernstein: Omnibus” and “John Gielgud: Ages of Man.” Between them, they’ll open your eyes to the unlimited possibilities of TV as a force for cultural good–and fill you with despair at the fact that such high-minded programming has largely disappeared from the small screen.

“Omnibus” was a cultural TV magazine underwritten by the Ford Foundation that shuttled among the three networks in the ’50s. Hosted by Alistair Cooke, it offered viewers glimpses of everything from Orson Welles’ “King Lear” to Mike Nichols and Elaine May, but it is best remembered by historians of American music for having introduced Leonard Bernstein to TV audiences. Unlike his later “Young People’s Concerts,” Bernstein’s seven “Omnibus” shows were made specifically for adult viewers, and they used the medium in a way that remains electrifyingly fresh to this day….

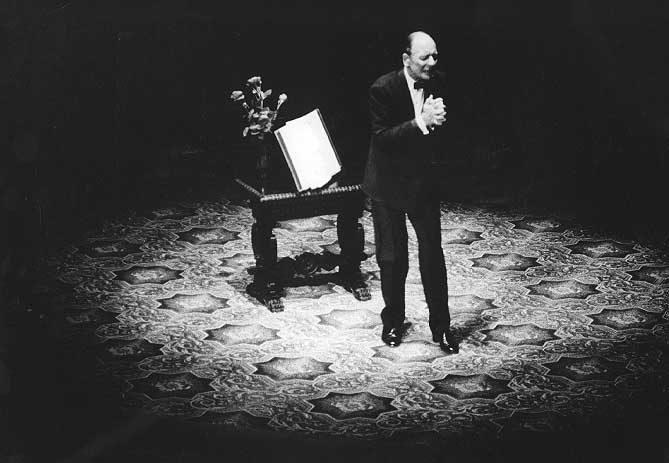

If anything, “Ages of Man” is more remarkable still, consisting as it does of a hundred-minute program in which the most admired classical actor of the 20th century, standing alone on a near-bare stage in a business suit, does nothing whatsoever but recite and talk about sonnets by and excerpts from the plays of William Shakespeare. Gielgud had performed this one-man show around the world between 1957 and 1966, when he brought its phenomenally successful run to a close by filming it for CBS. The black-and-white telecast, directed by Paul Bogart, is as devoid of high-tech gimmickry as a slab of rare roast beef: Virtually all of the show is shot in close-up, and Gielgud’s comments are as unobtrusive as the dirt-plain set. Yet it is precisely because of this simplicity that “Ages of Man” is so priceless…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt from “Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony,” Leonard Bernstein’s first Omnibus telecast:

TT: Almanac

“The basic stimulus to the intelligence is doubt, a feeling that the meaning of an experience is not self-evident.”

W.H. Auden, “The Protestant Mystics”

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• La Cage aux Folles (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Driving Miss Daisy * (drama, G, possible for smart children, closes Apr. 9, reviewed here)

• The Importance of Being Earnest (high comedy, G, just possible for very smart children, closes July 3, reviewed here)

• Lombardi (drama, G/PG-13, a modest amount of adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Million Dollar Quartet (jukebox musical, G, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Angels in America (drama, PG-13/R, adult subject matter, extended through Apr. 24, reviewed here)

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• Molly Sweeney (drama, G, too serious for children, extended through Apr. 10, reviewed here)

• Play Dead (theatrical spook show, PG-13, utterly unsuitable for easily frightened children or adults, reviewed here)

IN WASHINGTON, D.C.:

• Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (drama, PG-13/R, Washington remounting of Chicago production, adult subject matter, closes Apr. 10, Chicago run reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• Black Tie (comedy, PG-13, closes Mar. 27, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN SARASOTA, FLA.:

• Twelve Angry Men (drama, G, closes Mar. 26, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN ORLANDO, FLA.:

• A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Pride and Prejudice (comedy, G, playing in rotating repertory through Mar. 19-20, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN MINNEAPOLIS:

• Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (drama, PG-13/R, Minneapolis remounting of Phoenix production, adult subject matter and violence, Phoenix run reviewed here)

TT: Almanac

“In societies with fewer opportunities for amusement, it was also easier to tell a mere wish from a real desire. If, in order to hear some music, a man has to wait for six months and then walk twenty miles, it is easy to tell whether the words, ‘I should like to hear some music,’ mean what they appear to mean, or merely, ‘At this moment I should like to forget myself.’ When all he has to do is press a switch, it is more difficult. He may easily come to believe that wishes can come true.”

W.H. Auden, “Interlude: West’s Disease”

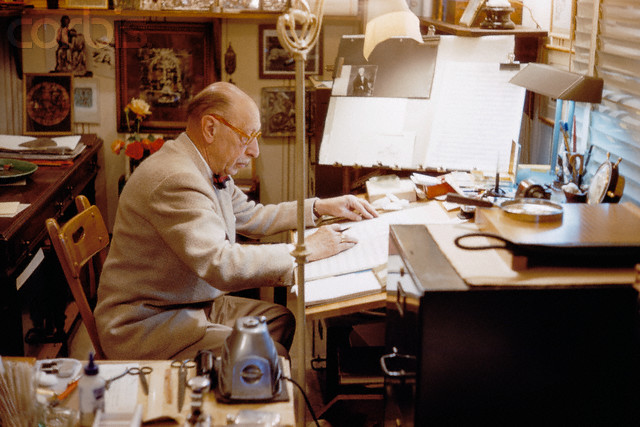

TT: Snapshot

Virgil Thomson talks about ragtime in Kansas City:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“One can only blaspheme if one believes.”

W.H. Auden, “Concerning the Unpredictable”

TT: Done and done (and done and done)

Danse Russe, the backstage comedy about the making of The Rite of Spring on which Paul Moravec and I have been working for the past few months, is done. I signed off on the piano-vocal score over the weekend, and Paul made his final corrections and shipped the finished product off to his publishers yesterday. It is now going out to the members of the cast of the first production of our second opera, which opens in Philadelphia on April 28. All that remains for Paul to do (and it is, lest we forget, a big “all”) is finish orchestrating the score, a back-breaking job in which I play no part. My job is pretty much over until the show goes into rehearsal next month.

Danse Russe, the backstage comedy about the making of The Rite of Spring on which Paul Moravec and I have been working for the past few months, is done. I signed off on the piano-vocal score over the weekend, and Paul made his final corrections and shipped the finished product off to his publishers yesterday. It is now going out to the members of the cast of the first production of our second opera, which opens in Philadelphia on April 28. All that remains for Paul to do (and it is, lest we forget, a big “all”) is finish orchestrating the score, a back-breaking job in which I play no part. My job is pretty much over until the show goes into rehearsal next month.

I have to admit that I don’t feel quite as excited as I did when we delivered the finished score of The Letter to the Santa Fe Opera. This is mostly because Danse Russe is, after all, our second opera. It’s not that we’re jaded–writing a comic opera is a very different proposition from writing an opera noir–but having been around the track once, we already knew which way to go to get to the finish line.

Almost as important, though, is the fact that my plate is piled high with work these days. In addition to wrapping up Danse Russe, I’ve been working on the first draft of my Duke Ellington biography and directing the first staged reading of Satchmo at the Waldorf, my first play. That’s a lot of firsts in a row, and when you factor in the fact that I knock out a minimum of six columns for The Wall Street Journal and write a twenty-five-hundred-word essay for Commentary each month, it means that I’m pretty damned busy.

So no, I didn’t break the neck of a bottle of champagne yesterday, nor do I plan to do so today. Instead, I’ll be working on a pile on expense reports, an indispensable part of the life of a peripatetic drama critic, and wishing I were in Winter Park with Mrs. T. Tomorrow I’ll present a literary award (about which more after it happens) and attend a preview of the Broadway revival of That Championship Season, and on Thursday I’ll fly back down to Orlando and my beloved spouse.

It turns out that finishing an opera, like finishing a hat, isn’t quite so big a deal when you’ve made a lot of hats. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t big enough:

There’s a part of you always standing by,

Mapping out the sky,

Finishing a hat…

Starting on a hat…

Finishing a hat…

Look, I made a hat…

Where there never was a hat.

And that’s that. For today, anyway.

UPDATE: A friend writes:

It comes with the artistic temperament. Wagner said, after Die Walküre, “Ach, just more verdammte gods…maybe I’ll burn them all!” Don’t forget to feel happy and proud of yourself. All the things in the pipeline should never distract from any one of them.

That’s good advice from a good friend.