“Among the repulsions of atheism for me has been its drastic uninterestingness as an intellectual position. Where was the ingenuity, the ambiguity, the humanity (in the Harvard sense) of saying that the universe just happened to happen and that when we’re dead we’re dead?”

“Among the repulsions of atheism for me has been its drastic uninterestingness as an intellectual position. Where was the ingenuity, the ambiguity, the humanity (in the Harvard sense) of saying that the universe just happened to happen and that when we’re dead we’re dead?”

John Updike, Self-Consciousness: Memoirs

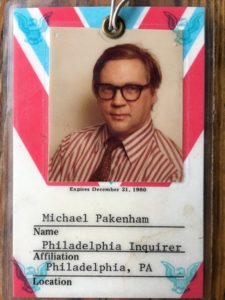

Michael, who died yesterday at the age of eighty-five, was the last of my journalistic mentors, the older men who went out of their way to show me the ropes. He was, as they say, a character, a newspaperman who had started out as a reporter at the Chicago Tribune and was old enough to have put in a stretch at Chicago’s

Michael, who died yesterday at the age of eighty-five, was the last of my journalistic mentors, the older men who went out of their way to show me the ropes. He was, as they say, a character, a newspaperman who had started out as a reporter at the Chicago Tribune and was old enough to have put in a stretch at Chicago’s  Michael’s editorial page was my finishing school. He taught me how to write short, fast, and with the kind of crisp immediacy you don’t learn from reviewing the Kansas City Philharmonic. He insisted that everyone who worked for him do everything there was to be done, from knocking out two-inch quickies about the school board to putting together the daily letters-to-the-editor column, and I learned as much from rotating through my varied tasks as I did from watching him blue-pencil my copy. On one never-to-be-forgotten occasion, he actually sent me to Albany to cover the release of New York’s state budget, about which I knew only slightly more than nothing, and made damned sure I got my facts straight. Nor will I soon forget the weekend when he called me at home and said, “The Berlin Wall has fallen. Get in your car and drive into town—we’ve got to redo the editorial page right now.” So we did, with wonder and awe.

Michael’s editorial page was my finishing school. He taught me how to write short, fast, and with the kind of crisp immediacy you don’t learn from reviewing the Kansas City Philharmonic. He insisted that everyone who worked for him do everything there was to be done, from knocking out two-inch quickies about the school board to putting together the daily letters-to-the-editor column, and I learned as much from rotating through my varied tasks as I did from watching him blue-pencil my copy. On one never-to-be-forgotten occasion, he actually sent me to Albany to cover the release of New York’s state budget, about which I knew only slightly more than nothing, and made damned sure I got my facts straight. Nor will I soon forget the weekend when he called me at home and said, “The Berlin Wall has fallen. Get in your car and drive into town—we’ve got to redo the editorial page right now.” So we did, with wonder and awe. Michael spent his old age living in a country house in Pennsylvania that was too far from the beaten path to allow for easy commuting. My duties as a New York drama critic had become so all-consuming that it was all but impossible for me to visit him there, and our meetings, alas, became vanishingly rare, though he made the long trip into New York to give a toast at my wedding to Mrs. T. By then he had fallen in love and settled down with Rosalie, his beloved wife, who survives him. She will have no shortage of indelible memories to comfort her. Neither will I.

Michael spent his old age living in a country house in Pennsylvania that was too far from the beaten path to allow for easy commuting. My duties as a New York drama critic had become so all-consuming that it was all but impossible for me to visit him there, and our meetings, alas, became vanishingly rare, though he made the long trip into New York to give a toast at my wedding to Mrs. T. By then he had fallen in love and settled down with Rosalie, his beloved wife, who survives him. She will have no shortage of indelible memories to comfort her. Neither will I. Even more important to me, though, is the now-remarkable fact that my mother and father got married in 1947 and stayed that way. It would be an understatement to say that they didn’t always get along—they actually separated briefly the year before I was born—but by the time my brother and I were old enough to understand the meaning of the word “divorce,” it was taken for granted that they would never get one. They were in it for better or worse, and the longer they lived, the clearer it became to all who knew them that they’d been wise beyond their years to ride out the storms in the home that they’d made for one another, and for us.

Even more important to me, though, is the now-remarkable fact that my mother and father got married in 1947 and stayed that way. It would be an understatement to say that they didn’t always get along—they actually separated briefly the year before I was born—but by the time my brother and I were old enough to understand the meaning of the word “divorce,” it was taken for granted that they would never get one. They were in it for better or worse, and the longer they lived, the clearer it became to all who knew them that they’d been wise beyond their years to ride out the storms in the home that they’d made for one another, and for us. While I’ve never been one to repine, it’s hard not to spend a fair amount of time playing the what-if game once you get to be my age. Fortunately for me, I’m much more than happy enough with What-Is not to lose sleep over What-If, though anyone who

While I’ve never been one to repine, it’s hard not to spend a fair amount of time playing the what-if game once you get to be my age. Fortunately for me, I’m much more than happy enough with What-Is not to lose sleep over What-If, though anyone who  In addition to “The Band’s Visit,” my 15-year tenure as the Journal’s drama critic has seen the arrival on Broadway of such memorable shows as “Avenue Q,” “Dear Evan Hansen,” “Fun Home,” “Hamilton,” “The Light in the Piazza” and “The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee.” But all of them, even “Hamilton,” are small-to-smallish-scale musicals that either originated off Broadway or were developed at regional theaters elsewhere in America. What I’m not seeing are any considerable number of first-rate large-scale Broadway musicals, the modern-day counterparts of such beloved golden-age shows as “Oklahoma!” and “Guys and Dolls.” Instead, we’re getting more and more of what I call “commodity musicals,” unchallenging confections like “Mean Girls,” “Frozen” and “School of Rock” that are more or less slavishly adapted from Hollywood hits of the past…

In addition to “The Band’s Visit,” my 15-year tenure as the Journal’s drama critic has seen the arrival on Broadway of such memorable shows as “Avenue Q,” “Dear Evan Hansen,” “Fun Home,” “Hamilton,” “The Light in the Piazza” and “The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee.” But all of them, even “Hamilton,” are small-to-smallish-scale musicals that either originated off Broadway or were developed at regional theaters elsewhere in America. What I’m not seeing are any considerable number of first-rate large-scale Broadway musicals, the modern-day counterparts of such beloved golden-age shows as “Oklahoma!” and “Guys and Dolls.” Instead, we’re getting more and more of what I call “commodity musicals,” unchallenging confections like “Mean Girls,” “Frozen” and “School of Rock” that are more or less slavishly adapted from Hollywood hits of the past… Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title. Mrs. T and I recently watched Bill Forsyth’s

Mrs. T and I recently watched Bill Forsyth’s  It’s a treadmill of sorts, but a benign and stimulating one, and my employers give me a safety valve by letting me go elsewhere from time to time to work on the plays and opera libretti that I started writing a few years ago. What with that freedom, the extended reviewing trips to Florida that Mrs. T and I make every winter, and the commonplace comforts of the rural farmhouse in Connecticut where we spend much of our time when I’m not on the aisle in Manhattan, it would be churlish for me to complain about the shape that my life has taken in middle age. Nobody has to tell me that most people have it a whole lot harder.

It’s a treadmill of sorts, but a benign and stimulating one, and my employers give me a safety valve by letting me go elsewhere from time to time to work on the plays and opera libretti that I started writing a few years ago. What with that freedom, the extended reviewing trips to Florida that Mrs. T and I make every winter, and the commonplace comforts of the rural farmhouse in Connecticut where we spend much of our time when I’m not on the aisle in Manhattan, it would be churlish for me to complain about the shape that my life has taken in middle age. Nobody has to tell me that most people have it a whole lot harder. My

My  I don’t know when Mrs. T and I will be back in Sanibel again, or when we’ll

I don’t know when Mrs. T and I will be back in Sanibel again, or when we’ll  As usual with Mr. Ayckbourn, “A Brief History of Women” arises from an ingenious structural premise: All four scenes take place on the ground floor of the same country house at 20-year intervals, the first in 1925 and the last in 1985. In the first scene, Anthony Spates (played by Antony Eden), the only character who appears throughout the play, is a part-time servant to the owners of Kirkbridge Manor, an aristocratic couple who are on the outs. In 1945 the manor has been turned into a prep school where Anthony teaches, contriving to get himself fired for engaging in hanky-panky with a colleague. By 1965 it’s become an arts center that he runs—not very well, one gathers, though he does find a wife there—and in the last part, the great house has been done over as a hotel of which Anthony is the part-time manager and where he meets a 97-year-old guest who once upon a time was the unhappy lady of Kirkbridge Manor.

As usual with Mr. Ayckbourn, “A Brief History of Women” arises from an ingenious structural premise: All four scenes take place on the ground floor of the same country house at 20-year intervals, the first in 1925 and the last in 1985. In the first scene, Anthony Spates (played by Antony Eden), the only character who appears throughout the play, is a part-time servant to the owners of Kirkbridge Manor, an aristocratic couple who are on the outs. In 1945 the manor has been turned into a prep school where Anthony teaches, contriving to get himself fired for engaging in hanky-panky with a colleague. By 1965 it’s become an arts center that he runs—not very well, one gathers, though he does find a wife there—and in the last part, the great house has been done over as a hotel of which Anthony is the part-time manager and where he meets a 97-year-old guest who once upon a time was the unhappy lady of Kirkbridge Manor.