In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I write about Slow Art Day. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Saturday is Slow Art Day, an annual event in which 156 museums and art galleries in the U.S. and around the world are participating this year. Here’s how it works:

• Sign up at a local museum or gallery. (You can do so here.)

• Show up on Saturday, then “look slowly—5-10 minutes—at each piece of pre-assigned art.”

• Show up on Saturday, then “look slowly—5-10 minutes—at each piece of pre-assigned art.”

• Discuss your experience with other participants. Each institution has its own arrangements for doing so, but “what all the events share is the focus on slow looking and its transformative power.”…

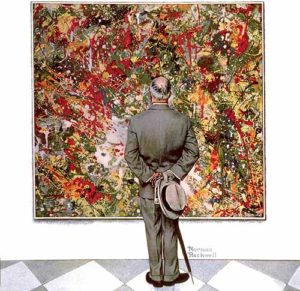

I think Phil Terry, the founder of Slow Art Day, is onto something important. As he explained in a 2011 interview with ARTnews magazine, “My wife kept dragging me to museums. I didn’t know how to look at art. Like most people, I would walk by quickly.” Then he spent a full hour looking at “Fantasia,” a spectacularly complex 1943 abstract painting by Hans Hofmann that belongs to the University of California’s Berkeley Art Museum, and found the unfamiliar experience to be galvanizing. According to one survey, most people spend roughly 17 seconds looking at each individual painting during a museum visit. That’s why Mr. Terry started Slow Art Day—to encourage all of us to slow down and see more of what’s there to be seen in a great work of art….

I am, I blush to admit, a bit of a galloper when it comes to museumgoing, just as I habitually eat too fast. On the other hand, I also collect art, and I’ve learned from doing so that the more time you spend looking at a painting of quality, the more fully it reveals its secrets, in much the same way that you come to understand a novel more completely by re-reading it. This is true of all important art, regardless of medium…

I am, I blush to admit, a bit of a galloper when it comes to museumgoing, just as I habitually eat too fast. On the other hand, I also collect art, and I’ve learned from doing so that the more time you spend looking at a painting of quality, the more fully it reveals its secrets, in much the same way that you come to understand a novel more completely by re-reading it. This is true of all important art, regardless of medium…

The difference—at least in theory—is that performed art, unlike visual art, must be experienced across a pre-defined span of time. It takes a half-hour, more or less, to listen to a symphony by Mozart or Haydn, and the only way to speed up the process is to get up and leave the hall. Unfortunately, a fast-growing number of people now do most of their listening on computers and hand-held devices of various kinds. Even for a seasoned music lover, the temptation to click from piece to piece in search of instant gratification can be overwhelming…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

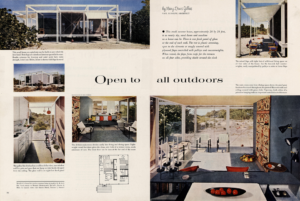

In Saturday’s Wall Street Journal “Masterpiece” column I wrote about Paul Rudolph’s Walker Guest House, located on Florida’s Sanibel Island, and the

In Saturday’s Wall Street Journal “Masterpiece” column I wrote about Paul Rudolph’s Walker Guest House, located on Florida’s Sanibel Island, and the  Today Rudolph, who died in 1997, is best remembered for his public buildings in the now-unfashionable “brutalist” style, many of which have either been torn down or are earmarked for demolition. But it was his Florida vacation homes that put him on the map, so much so that the Walker Guest House was the subject of an enthusiastic 1954 two-page spread in McCall’s (“This small summer house…is as nearly sky, sand dunes and sunshine as a house can be”). Their continuing fame is well deserved. Like Frank Lloyd Wright’s 880-square-foot Seth Peterson Cottage, another miniature masterpiece and the smallest of the “Usonian” houses that Wright designed for middle-class homeowners, the Walker Guest House is so compact and logically organized that to step inside feels almost as though you’re putting on a piece of clothing….

Today Rudolph, who died in 1997, is best remembered for his public buildings in the now-unfashionable “brutalist” style, many of which have either been torn down or are earmarked for demolition. But it was his Florida vacation homes that put him on the map, so much so that the Walker Guest House was the subject of an enthusiastic 1954 two-page spread in McCall’s (“This small summer house…is as nearly sky, sand dunes and sunshine as a house can be”). Their continuing fame is well deserved. Like Frank Lloyd Wright’s 880-square-foot Seth Peterson Cottage, another miniature masterpiece and the smallest of the “Usonian” houses that Wright designed for middle-class homeowners, the Walker Guest House is so compact and logically organized that to step inside feels almost as though you’re putting on a piece of clothing….