From 2010:

I don’t think there’s much chance that anyone will remember me a hundred years from today, unless they happen to be perusing Gail Levin’s files and stumble across her research into the provenance of “Apples on Table,” in which case they will know that a copy of this exquisite hommage to Cézanne was once owned by an otherwise unknown couple named “Terry and Hilary Teachout.” By then Mrs. T and I will be long gone, and our handsome print will presumably be giving pleasure to a person or persons as yet unborn…

Read the whole thing here.

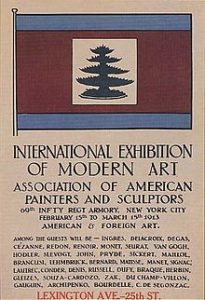

A historian I know reminded me the other day that Theodore Roosevelt attended and

A historian I know reminded me the other day that Theodore Roosevelt attended and  It’s easy—too easy—to sneer at the alleged philistinism of Roosevelt’s response to “Nude Descending a Staircase.” What I find vastly more interesting, by contrast, is that he had an opinion about the painting, and expressed it so clearly and compellingly. Can you think of another president who’s had anything whatsoever to say about modern art?

It’s easy—too easy—to sneer at the alleged philistinism of Roosevelt’s response to “Nude Descending a Staircase.” What I find vastly more interesting, by contrast, is that he had an opinion about the painting, and expressed it so clearly and compellingly. Can you think of another president who’s had anything whatsoever to say about modern art? Needless to say, I take it for granted that politicans who talk about art for public consumption have been carefully briefed in advance. It’s no secret that President Kennedy’s alleged interest in the fine arts was in fact a concoction of his aides (his taste ran more to the novels of Ian Fleming). But Obama certainly gave a convincing impression in this interview of being a man who takes fiction seriously, and we have it on

Needless to say, I take it for granted that politicans who talk about art for public consumption have been carefully briefed in advance. It’s no secret that President Kennedy’s alleged interest in the fine arts was in fact a concoction of his aides (his taste ran more to the novels of Ian Fleming). But Obama certainly gave a convincing impression in this interview of being a man who takes fiction seriously, and we have it on  Which brings us back to Theodore Roosevelt, who happens to be the only American president to date who has himself inspired an indisputably first-class work of visual art, the official White House portrait that John Singer Sargent painted in 1903. Roosevelt, as well he should have, liked it very much, though I wouldn’t have been surprised had he taken against it, given the circumstances in which it was painted. According to Edmund Morris, “[t]he noticeable sadness in [Roosevelt’s] eyes may reflect the fact that his wife, even as he posed, was suffering her second miscarriage in two years.”

Which brings us back to Theodore Roosevelt, who happens to be the only American president to date who has himself inspired an indisputably first-class work of visual art, the official White House portrait that John Singer Sargent painted in 1903. Roosevelt, as well he should have, liked it very much, though I wouldn’t have been surprised had he taken against it, given the circumstances in which it was painted. According to Edmund Morris, “[t]he noticeable sadness in [Roosevelt’s] eyes may reflect the fact that his wife, even as he posed, was suffering her second miscarriage in two years.”

Casting, the saying goes, is two-thirds of directing, and Mr. Amster has dealt himself a handful of aces. Christina DeCicco plays Billie, a chorus girl turned rich man’s mistress, in the familiar manner of Holliday, yet there’s nothing mechanical about the way in which she evokes her model. She wears the role like a second skin, punching the laugh lines in a voice of solid brass while never letting us forget that beneath her sexy surface, Billie is a painfully vulnerable woman who hates herself for having hitched her wagon to the dark star of Harry Brock (Norm Boucher), a boorish thug who claims to “love that broad” but slaps her around whenever she fails to toe the line.

Casting, the saying goes, is two-thirds of directing, and Mr. Amster has dealt himself a handful of aces. Christina DeCicco plays Billie, a chorus girl turned rich man’s mistress, in the familiar manner of Holliday, yet there’s nothing mechanical about the way in which she evokes her model. She wears the role like a second skin, punching the laugh lines in a voice of solid brass while never letting us forget that beneath her sexy surface, Billie is a painfully vulnerable woman who hates herself for having hitched her wagon to the dark star of Harry Brock (Norm Boucher), a boorish thug who claims to “love that broad” but slaps her around whenever she fails to toe the line.