I love my life, but there are aspects of it that I find trying. One of them is that I have no weekends. Far more often than not, I either see shows on Saturdays and Sundays (which really does feel like work, believe it or not, though far less so when the shows are good) or I’m out on the road. When I’m at home, there’s a better-than-even chance that I’ll be spending at least part of the weekend working on pieces that need to be finished and filed by Monday or Tuesday of the following week. This isn’t to say that I never have time off: the problem is that it comes at wildly unpredictable intervals.

It wasn’t always this way. Before I became a full-time freelancer and, somewhat later, an increasingly peripatetic drama critic, I worked five days a week and took Saturdays and Sundays off, just like most of the rest of my fellow Americans. The downside of this arrangement was, of course, that I spent between eight and ten hours each day sitting on my backside in an office. (At one point in my life, I actually punched a time clock.) The upside was that I walked away from the job every Friday at six o’clock, more or less, shedding it like a raincoat that I hung up in the hall closet as soon as I got home.

It wasn’t always this way. Before I became a full-time freelancer and, somewhat later, an increasingly peripatetic drama critic, I worked five days a week and took Saturdays and Sundays off, just like most of the rest of my fellow Americans. The downside of this arrangement was, of course, that I spent between eight and ten hours each day sitting on my backside in an office. (At one point in my life, I actually punched a time clock.) The upside was that I walked away from the job every Friday at six o’clock, more or less, shedding it like a raincoat that I hung up in the hall closet as soon as I got home.

Nowadays, by contrast, I work at home and am free to schedule my days as I please, subject only to the demands of my deadlines, which are themselves surprisingly flexible (up to a point, Lord Copper!). I come and go as I please, and unless I have to catch a morning plane, I almost never use an alarm clock to roust myself out of bed. Nobody has to tell me what a boon this is: I remember with glaring clarity what it felt like to go to an office every weekday, and I hope I never have to do it again.

The price I pay for this freedom, though, is that it takes a conscious and deliberate act of will for me to go completely off duty. Left to my own devices, there’s a pretty good chance that I’ll write instead of taking it easy. Even when I’m not writing, I spend far too much time staring at the screen of my MacBook, which has become less a tool than an appendage of my consciousness, a device that far too often distracts me from the supremely important task of living in, and relishing, the precious, fleeting moments that are my life.

“To be happy, not in memory but in the moment, is the shining star on the tree of life,” I wrote in this space on the day that, eleven years ago, I trimmed the first Christmas tree that I shared with Mrs. T. The two of us were happy that day, and we knew it while it was happening. We’ve since shared many such moments, most of which I’ve had the good sense not to take for granted. I sometimes wonder whether my self-directed, weekend-free way of life is more or less conducive to properly appreciating those moments. In the end, of course, it doesn’t matter. This is my life, for better and worse, and it’s my job to get the most out of it that can possibly be gotten in the time remaining—which sometimes means doing nothing in particular.

It happens that I don’t have to do anything in particular today. I have no deadlines to hit and no show to see. I slept in this morning, and I plan (if you want to call it that) to spend the rest of the day re-reading a novel about which I’m not writing, watching Max Ophüls’ La Ronde on TCM, and dining with Mrs. T tonight. We have a refrigerator full of tasty leftovers, and I’m inclined to think that we’d do well to eat some of them on the tree-lined patio of our rented Winter Park bungalow, which is as pretty as the picture that you can see on the right. Or not: it’s Valentine’s Day, after all, and if Mrs. T prefers to eat out instead, I’m all for it.

It happens that I don’t have to do anything in particular today. I have no deadlines to hit and no show to see. I slept in this morning, and I plan (if you want to call it that) to spend the rest of the day re-reading a novel about which I’m not writing, watching Max Ophüls’ La Ronde on TCM, and dining with Mrs. T tonight. We have a refrigerator full of tasty leftovers, and I’m inclined to think that we’d do well to eat some of them on the tree-lined patio of our rented Winter Park bungalow, which is as pretty as the picture that you can see on the right. Or not: it’s Valentine’s Day, after all, and if Mrs. T prefers to eat out instead, I’m all for it.

Today, in other words, looks very much like my version of a weekend. So why on earth am I spending it writing these words? It’s time for a decisive act of work-denying will. I’ll see you tomorrow—or maybe the day after tomorrow.

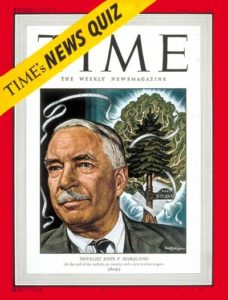

This essay about John P. Marquand’s

This essay about John P. Marquand’s  With the practiced skill of a Hollywood director, Marquand turns the clock back a quarter-century. We learn that Charles is the oldest son of a New England family headed by a flighty, unsound man who frittered away a small fortune and thereafter was viewed with suspicion by his ultra-proper friends and neighbors. When Charles falls in love with the daughter of one of Clyde’s oldest families, he discovers that his father’s irresponsibility has cast a cloud over his own reputation and that he is not deemed an acceptable suitor. Cruelly hurt by his inability to vault the high walls of caste, he puts Clyde behind him, goes to New York, and seeks a less provincial life. For a time he thinks he has found it, but then he looks into the mirror and realizes that he has spent the whole of his life measuring himself by the yardstick of a town that time has left behind. Not even the promotion he has sought for so long can erase the chilling suspicion that his worldly success is a handful of dust:

With the practiced skill of a Hollywood director, Marquand turns the clock back a quarter-century. We learn that Charles is the oldest son of a New England family headed by a flighty, unsound man who frittered away a small fortune and thereafter was viewed with suspicion by his ultra-proper friends and neighbors. When Charles falls in love with the daughter of one of Clyde’s oldest families, he discovers that his father’s irresponsibility has cast a cloud over his own reputation and that he is not deemed an acceptable suitor. Cruelly hurt by his inability to vault the high walls of caste, he puts Clyde behind him, goes to New York, and seeks a less provincial life. For a time he thinks he has found it, but then he looks into the mirror and realizes that he has spent the whole of his life measuring himself by the yardstick of a town that time has left behind. Not even the promotion he has sought for so long can erase the chilling suspicion that his worldly success is a handful of dust: