“It was that night toward the end of rehearsals when everything finally comes together, and you feel that if they’d give you a chance, you could direct the affairs of nations. You could bring the entire world into harmony—you’re that good a director. Of course a night like that is usually followed by a dress rehearsal where absolutely everything goes to hell—there’ll be a short circuit in the lighting and your stage manager will come down with the mumps and your leading lady will trip on the hem of her costume and fall into the orchestra pit—but knowing that doesn’t make a speck of difference. For the moment, you’re on top of the world.”

“It was that night toward the end of rehearsals when everything finally comes together, and you feel that if they’d give you a chance, you could direct the affairs of nations. You could bring the entire world into harmony—you’re that good a director. Of course a night like that is usually followed by a dress rehearsal where absolutely everything goes to hell—there’ll be a short circuit in the lighting and your stage manager will come down with the mumps and your leading lady will trip on the hem of her costume and fall into the orchestra pit—but knowing that doesn’t make a speck of difference. For the moment, you’re on top of the world.”

Jon Hassler, The Love Hunter (courtesy of Mrs. T)

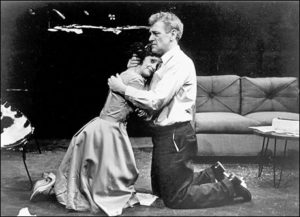

“The House of Blue Leaves,” first performed in 1971, is a fearsomely and famously tricky play to bring off, for it illustrates Mr. Guare’s pithy dictum that “farce is tragedy speeded up.” It’s the story of Artie (Greg Longenhagen), an inept blue-collar songwriter from Queens whose wife, Bananas (Rachel Burttram), is clinically depressed beyond hope of cure. He’s fallen in love with Bunny (Carrie Lund), his downstairs neighbor, a brassy golddigger who believes, God knows why, in the commercial potential of Artie’s songs (one of which rhymes “comical” with “yarmulke”) and wants him to send Bananas to an insane asylum, go to Hollywood and make his fortune—meaning her fortune.

“The House of Blue Leaves,” first performed in 1971, is a fearsomely and famously tricky play to bring off, for it illustrates Mr. Guare’s pithy dictum that “farce is tragedy speeded up.” It’s the story of Artie (Greg Longenhagen), an inept blue-collar songwriter from Queens whose wife, Bananas (Rachel Burttram), is clinically depressed beyond hope of cure. He’s fallen in love with Bunny (Carrie Lund), his downstairs neighbor, a brassy golddigger who believes, God knows why, in the commercial potential of Artie’s songs (one of which rhymes “comical” with “yarmulke”) and wants him to send Bananas to an insane asylum, go to Hollywood and make his fortune—meaning her fortune.

• “I felt at home in a theater. I loved being part of an audience. All the rules—the audience has to see the play on a certain date at a certain time in a certain place in a certain seat. You watched the stage in unison with strangers. The theater had intermissions where you could smoke cigarettes in the lobby and imagine you were interesting. The theater made everybody in the audience behave better, as if they were all in on the same secret. I found it amazing that what was up on that stage could make these people who didn’t know each other laugh, respond, gasp in exactly the same way at the same time.”

• “I felt at home in a theater. I loved being part of an audience. All the rules—the audience has to see the play on a certain date at a certain time in a certain place in a certain seat. You watched the stage in unison with strangers. The theater had intermissions where you could smoke cigarettes in the lobby and imagine you were interesting. The theater made everybody in the audience behave better, as if they were all in on the same secret. I found it amazing that what was up on that stage could make these people who didn’t know each other laugh, respond, gasp in exactly the same way at the same time.” • “I always liked plays to be funny and early on stumbled upon the truth that farce is tragedy speeded up.”

• “I always liked plays to be funny and early on stumbled upon the truth that farce is tragedy speeded up.”

When Nat Hentoff died on Saturday at the age of 91, one of his sons broke the news on Twitter. That might well have amused Hentoff, a technological Luddite who never abandoned the typewriter and never established a social-media beachhead. He might also have been amused—if grimly so—by the fact that many of his obituaries devoted more space to his latter-day career as a civil libertarian than to the writings about jazz with which he made his journalistic name. Sad to say, that makes perfect sense. Not only had the music that Hentoff loved best (he died listening to the records of Billie Holiday) ceased to be central to the American cultural conversation by the time of his death, but he was a First Amendment absolutist who lived to see free speech under siege in his native land, which explains why his impassioned writings about it should now loom so large in memory. Still, few who know his work at all well are in doubt that he will be remembered longest as one of the foremost jazz commentators of the 20th century.

When Nat Hentoff died on Saturday at the age of 91, one of his sons broke the news on Twitter. That might well have amused Hentoff, a technological Luddite who never abandoned the typewriter and never established a social-media beachhead. He might also have been amused—if grimly so—by the fact that many of his obituaries devoted more space to his latter-day career as a civil libertarian than to the writings about jazz with which he made his journalistic name. Sad to say, that makes perfect sense. Not only had the music that Hentoff loved best (he died listening to the records of Billie Holiday) ceased to be central to the American cultural conversation by the time of his death, but he was a First Amendment absolutist who lived to see free speech under siege in his native land, which explains why his impassioned writings about it should now loom so large in memory. Still, few who know his work at all well are in doubt that he will be remembered longest as one of the foremost jazz commentators of the 20th century. He wrote about many other kinds of artists, among them Ray Charles, Bob Dylan and Bob Wills, for the Journal and virtually every other newspaper and magazine of consequence. But it was jazz that spoke most strongly to him, and it may well be that his signal achievement as an advocate was to help choose the roster of musicians who performed on “The Sound of Jazz,” the legendary 1957 TV special on which the illustrious likes of Holiday, Count Basie, Roy Eldridge, Coleman Hawkins, Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Pee Wee Russell, Ben Webster and Lester Young were seen playing in a casual jam-session setting. “For me, it was a jazz fan’s fantasy come true,” Hentoff recalled 50 years after the show first aired on CBS. It was also a priceless gift to posterity: To this day “The Sound of Jazz” continues to be widely regarded as the finest jazz program ever telecast….

He wrote about many other kinds of artists, among them Ray Charles, Bob Dylan and Bob Wills, for the Journal and virtually every other newspaper and magazine of consequence. But it was jazz that spoke most strongly to him, and it may well be that his signal achievement as an advocate was to help choose the roster of musicians who performed on “The Sound of Jazz,” the legendary 1957 TV special on which the illustrious likes of Holiday, Count Basie, Roy Eldridge, Coleman Hawkins, Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Pee Wee Russell, Ben Webster and Lester Young were seen playing in a casual jam-session setting. “For me, it was a jazz fan’s fantasy come true,” Hentoff recalled 50 years after the show first aired on CBS. It was also a priceless gift to posterity: To this day “The Sound of Jazz” continues to be widely regarded as the finest jazz program ever telecast….