My late mother’s favorite actor, the charming and greatly loved star of Maverick and The Rockford Files, died on Saturday at the magnificent age of eighty-six. His Variety obituary reveals, among other admirable things, that he’d been married to the same woman since 1956. (Incidentally, they tied the knot sixteen days after they met.)

My late mother’s favorite actor, the charming and greatly loved star of Maverick and The Rockford Files, died on Saturday at the magnificent age of eighty-six. His Variety obituary reveals, among other admirable things, that he’d been married to the same woman since 1956. (Incidentally, they tied the knot sixteen days after they met.)

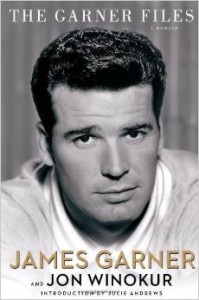

I admired Garner’s acting without reserve, and said so here in 2003. I also liked The Garner Files, his 2011 memoir, which I praised here. He didn’t make very many movies, preferring the small screen, but the finest of them are memorable, including The Americanization of Emily, The Great Escape, and Twilight, the last of which he contrived to steal right out from under Paul Newman and Gene Hackman. Best of all, though, was Burt Kennedy’s Support Your Local Sheriff!, a splendidly witty 1969 spoof western that has aged much more gracefully than the now-dated Blazing Saddles.

I plan to watch one of them this week in honor of the passing of a consummate craftsman who gave pleasure to millions of fans, myself among them.

* * *

To see a complete list of the answering-machine messages heard in the opening scenes of each episode of The Rockford Files, go here.

The theatrical trailer for Support Your Local Sheriff!:

I finally got a chance last week to see Nancy Buirski’s

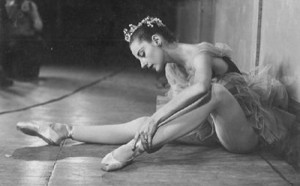

I finally got a chance last week to see Nancy Buirski’s  But Balanchine’s eye had already started to wander—as had Tallchief’s. They agreed to separate after the London season (their marriage was subsequently annulled), and no sooner did NYCB return to Manhattan than Balanchine began seeing Le Clercq in public. “I just love you to talk to, to go around with, play games, laugh like hell, etc.,” she told Robbins in a letter. “However, I’m in love with George. Maybe it’s a case of he got here first.” Devastated by what he saw as her betrayal, Robbins made The Cage, a chillingly angry portrait of a tribe of insect-women who kill the men with whom they mate. And though Tallchief remained the prima ballerina of New York City ballet for a few years more, it was Le Clercq for whom Balanchine made La Valse (1951, music by Ravel), a darkly unsettling vignette about a beautiful young girl who encounters a black-clad man at a party. He offers her a pair of black gloves into which the girl heedlessly plunges her hands. Then they waltz together with mad abandon until she collapses and dies.

But Balanchine’s eye had already started to wander—as had Tallchief’s. They agreed to separate after the London season (their marriage was subsequently annulled), and no sooner did NYCB return to Manhattan than Balanchine began seeing Le Clercq in public. “I just love you to talk to, to go around with, play games, laugh like hell, etc.,” she told Robbins in a letter. “However, I’m in love with George. Maybe it’s a case of he got here first.” Devastated by what he saw as her betrayal, Robbins made The Cage, a chillingly angry portrait of a tribe of insect-women who kill the men with whom they mate. And though Tallchief remained the prima ballerina of New York City ballet for a few years more, it was Le Clercq for whom Balanchine made La Valse (1951, music by Ravel), a darkly unsettling vignette about a beautiful young girl who encounters a black-clad man at a party. He offers her a pair of black gloves into which the girl heedlessly plunges her hands. Then they waltz together with mad abandon until she collapses and dies. Le Clercq contracted polio in 1956, when she was just twenty-six years old. She was one of the last people in America to develop that dread disease before Jonas Salk’s vaccine made it a thing of the past. It left her paralyzed from the waist down, and she never danced again. At first Balanchine nursed her devotedly, but in due course he began to see other women, and eventually he divorced her to pursue Suzanne Farrell.

Le Clercq contracted polio in 1956, when she was just twenty-six years old. She was one of the last people in America to develop that dread disease before Jonas Salk’s vaccine made it a thing of the past. It left her paralyzed from the waist down, and she never danced again. At first Balanchine nursed her devotedly, but in due course he began to see other women, and eventually he divorced her to pursue Suzanne Farrell. I was born in the year that Le Clercq stopped dancing, and I never met her. But not long before she died in 2000, I happened to see her sitting in her wheelchair on the promenade of the New York State Theater, mere paces away from an enlarged photo on the wall that showed her dancing gaily with Robbins in Bourrée Fantasque. With her white hair and pale, wrinkled skin, she looked like a chic ghost. A few months later I attended her memorial service, and felt, like everyone else who came to the State Theater that dark day, that I had somehow lost a friend.

I was born in the year that Le Clercq stopped dancing, and I never met her. But not long before she died in 2000, I happened to see her sitting in her wheelchair on the promenade of the New York State Theater, mere paces away from an enlarged photo on the wall that showed her dancing gaily with Robbins in Bourrée Fantasque. With her white hair and pale, wrinkled skin, she looked like a chic ghost. A few months later I attended her memorial service, and felt, like everyone else who came to the State Theater that dark day, that I had somehow lost a friend.

Mr. O’Connell has the perfect sense of timing that’s needed in order to sustain Mr. Ives’ comic tirades all the way to the payoff. A burly stand-up comedian turned classical actor who is blessed with a broad, expressive face, he’s equally adept at speaking verse and doing pratfalls….

Mr. O’Connell has the perfect sense of timing that’s needed in order to sustain Mr. Ives’ comic tirades all the way to the payoff. A burly stand-up comedian turned classical actor who is blessed with a broad, expressive face, he’s equally adept at speaking verse and doing pratfalls…. Classical music’s number-one news story is the plight of the Metropolitan Opera, whose general manager, Peter Gelb, is facing the possibility of a crippling strike. For that reason, what he said in a recent interview deserves to be quoted at length: “Grand opera is in itself a kind of a dinosaur of an art form….The question is not whether I think I’m doing a good job or not in trying to keep the [Metropolitan Opera] alive. It’s whether I’m doing a good job or not in the face of a cultural and social rejection of opera as an art form.”

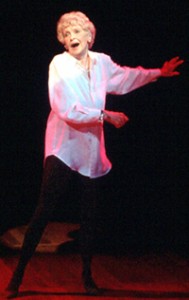

Classical music’s number-one news story is the plight of the Metropolitan Opera, whose general manager, Peter Gelb, is facing the possibility of a crippling strike. For that reason, what he said in a recent interview deserves to be quoted at length: “Grand opera is in itself a kind of a dinosaur of an art form….The question is not whether I think I’m doing a good job or not in trying to keep the [Metropolitan Opera] alive. It’s whether I’m doing a good job or not in the face of a cultural and social rejection of opera as an art form.” Stritch was past her prime when I became the drama critic of The Wall Street Journal, but I still had occasion to review her on a few noteworthy occasions, including a revival of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame in which she acquitted herself quite wonderfully well.

Stritch was past her prime when I became the drama critic of The Wall Street Journal, but I still had occasion to review her on a few noteworthy occasions, including a revival of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame in which she acquitted herself quite wonderfully well.