Mrs. T and I had occasion over the weekend to drive all the way across Florida and back again–a total of seven hours on the road–in a single day. Most of our longish trip was spent on a lengthy, lonely stretch of highway along which there is nothing to be seen but orange groves and sugar-cane trees. Then, to our surprise and relief, we finally passed through a city, a farm-and-fishing town called Clewiston whose population is 7,000, more or less, and whose city-limit sign, presumably in homage to the local cash crops, proclaims it to be “America’s Sweetest Town.”

Mrs. T and I had occasion over the weekend to drive all the way across Florida and back again–a total of seven hours on the road–in a single day. Most of our longish trip was spent on a lengthy, lonely stretch of highway along which there is nothing to be seen but orange groves and sugar-cane trees. Then, to our surprise and relief, we finally passed through a city, a farm-and-fishing town called Clewiston whose population is 7,000, more or less, and whose city-limit sign, presumably in homage to the local cash crops, proclaims it to be “America’s Sweetest Town.”

That charming boast put smiles on our travel-numbed faces, and we’d have pulled off the road and looked around had we not been in a moderate hurry to get where we were going. Alas, there’s not much of Clewiston to be seen from the window of a rental car roaring down Highway 80, just a modest assortment of storefronts, service stations, and fast-food restaurants. The only thing that caught my eye was a small sign that pointed the way to “John Boy Auditorium.” I took for granted that it was named after the character from The Waltons, but subsequent investigation disillusioned me. Sometimes truth is stranger than fiction, sometimes not.

“I wonder what it’d be like to live here,” I said. Mrs. T, who is a city girl from top to toe, responded by making a face. But I, having been raised in a town roughly comparable in size to Clewiston, gave my own question serious thought, and replied, “I know one thing–it’d be a lot different from the way it was when I was a boy.” She took my point at once.

“I wonder what it’d be like to live here,” I said. Mrs. T, who is a city girl from top to toe, responded by making a face. But I, having been raised in a town roughly comparable in size to Clewiston, gave my own question serious thought, and replied, “I know one thing–it’d be a lot different from the way it was when I was a boy.” She took my point at once.

When I was growing up in Smalltown, U.S.A., our main ties to the outside world were network TV and the public library. Our town had a grand total of two single-screen movie theaters, and there were no chain bookstores or record stores anywhere near us. For most of us, the world we saw was the world we knew. Everything is different now, be it in Smalltown or Clewiston. You can boot up your computer and connect instantly and without effort to an inconceivably vast universe of information. You’re only as isolated as you want to be.

Of course I’d miss a lot of things, starting with live theater, if I relocated from Manhattan to a rural town, but I wouldn’t be cut off from the world of art and culture, not by the longest of shots. Having lived in New York for more than a quarter of a century, I can’t know what it feels like to grow up in a small town today. That’s a different experience altogether. But were I now to withdraw to a place like Clewiston, I’d be bringing more than half a lifetime of accumulated cultural capital with me, and I suspect that I’d be able to live off the interest, so to speak, for the rest of my life.

We passed through Clewiston again on our way back to Sanibel Island. This time we paused long enough for me to visit the men’s room of the local McDonald’s, which was jammed to the walls with hungry patrons. By then the sun had set, and when I got back in the car, I said to Mrs. T, “I believe it’s time for some high culture.” I slid a CD of Joseph Szigeti playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto into the dashboard deck, and we listened hungrily to that most serene of recorded masterpieces, which can now be downloaded from anywhere in the world in a matter of seconds, as we drove through the darkness toward home.

We passed through Clewiston again on our way back to Sanibel Island. This time we paused long enough for me to visit the men’s room of the local McDonald’s, which was jammed to the walls with hungry patrons. By then the sun had set, and when I got back in the car, I said to Mrs. T, “I believe it’s time for some high culture.” I slid a CD of Joseph Szigeti playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto into the dashboard deck, and we listened hungrily to that most serene of recorded masterpieces, which can now be downloaded from anywhere in the world in a matter of seconds, as we drove through the darkness toward home.

Szigeti cut that recording in London in 1932, a quarter-century before I was born, and I first heard it in Smalltown forty years later, having read about it in a now-defunct, much-mourned music magazine called High Fidelity (for which I would later write record reviews) and ordered it from a store in Chicago called Rose Records (also defunct). Even then, the world was smaller than I knew. Now it’s smaller than I could possibly have imagined all those years ago. Does that make life better? I wonder about that, too–but I have no doubt that for people like myself, whether old or young, it eases the complicated solitude of being different in a very small town.

* * *

Joseph Szigeti plays an excerpt from the first movement of the Beethoven Violin Concerto, accompanied by Wilfrid Pelletier and the Orchestre de Radio-Canada:

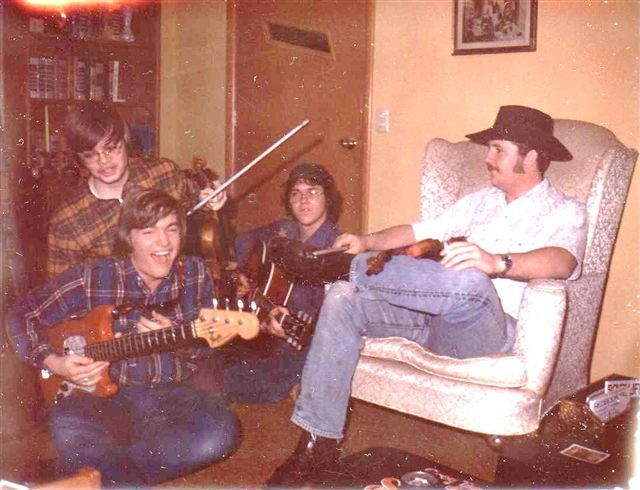

I’ve never had any trouble getting used to that fundamental reality of human life, for the very good reason that no one else in my extended family has ever been “professionally occupied with the arts.” Except for my mother’s father, who played the banjo for pleasure, I was the first one to play a musical instrument other than casually, as well as the first, so far as I know, to go to a classical concert or an art museum, or attend a professional production of a play.

I’ve never had any trouble getting used to that fundamental reality of human life, for the very good reason that no one else in my extended family has ever been “professionally occupied with the arts.” Except for my mother’s father, who played the banjo for pleasure, I was the first one to play a musical instrument other than casually, as well as the first, so far as I know, to go to a classical concert or an art museum, or attend a professional production of a play. It happens that Hugh Moreland, the character to whom Anthony Powell refers in the excerpt from A Dance to the Music of Time reprinted at the top of this posting, is a fictionalized version of Constant Lambert, the British composer-conductor-critic about whom I’ve written

It happens that Hugh Moreland, the character to whom Anthony Powell refers in the excerpt from A Dance to the Music of Time reprinted at the top of this posting, is a fictionalized version of Constant Lambert, the British composer-conductor-critic about whom I’ve written