JANUARY 9 Back to work, if you want to call it that: Mrs. T and I took a day trip to see “Marsden Hartley: American Modern” at the Naples Museum of Art, followed by dinner and the opening night of Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa at Florida Rep. Hartley’s work, like Friel’s, is near and dear to my heart–I own one of his lithographs–but it’s far easier to see his paintings in America’s regional museums than in big cities, which is why we made a point of seeing this unusually fine traveling exhibit, which has been making the rounds for the past few years without getting anywhere near New York City.

JANUARY 9 Back to work, if you want to call it that: Mrs. T and I took a day trip to see “Marsden Hartley: American Modern” at the Naples Museum of Art, followed by dinner and the opening night of Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa at Florida Rep. Hartley’s work, like Friel’s, is near and dear to my heart–I own one of his lithographs–but it’s far easier to see his paintings in America’s regional museums than in big cities, which is why we made a point of seeing this unusually fine traveling exhibit, which has been making the rounds for the past few years without getting anywhere near New York City.

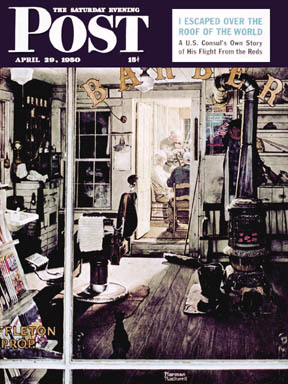

Across the hall was a Norman Rockwell show–pretty standard stuff for the most part, though I was pleased to see the original painting of “Solitaire” and a grisaille study for “Shuffleton’s Barbershop,” both of which are among the handful of Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers that I think deserve to be taken seriously as art. It was “Shuffleton’s Barbershop” that I had in mind when I wrote five years ago in the late, lamented Book that “at his occasional best, Rockwell really was worthy of comparison to the Dutch genre painters of the seventeenth century, such as Pieter de Hooch, whose work he admired and emulated….he managed to shake off the easy, jokey charm of his better-known canvases and cut straight to the heart of the matter.” (“Shuffleton’s Barbershop,” by the way, is Paul Johnson’s favorite Rockwell painting.)

Across the hall was a Norman Rockwell show–pretty standard stuff for the most part, though I was pleased to see the original painting of “Solitaire” and a grisaille study for “Shuffleton’s Barbershop,” both of which are among the handful of Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers that I think deserve to be taken seriously as art. It was “Shuffleton’s Barbershop” that I had in mind when I wrote five years ago in the late, lamented Book that “at his occasional best, Rockwell really was worthy of comparison to the Dutch genre painters of the seventeenth century, such as Pieter de Hooch, whose work he admired and emulated….he managed to shake off the easy, jokey charm of his better-known canvases and cut straight to the heart of the matter.” (“Shuffleton’s Barbershop,” by the way, is Paul Johnson’s favorite Rockwell painting.)

The Rockwell show appeared to be more to the liking of the patrons of the Naples Museum, whose architecture is very suburban–the interior suggests a cross between a shopping center and a gazillion-dollar Ramada Inn–and whose permanent collection is of modest interest. Dancing at Lughnasa, on the other hand, was a knockout, one of the best regional revivals I’ve covered for the Journal. Alas, we didn’t stay in Fort Myers long enough to get any kind of feel for the place, so all I can tell you is that Florida Rep is a company of real consequence and that you can get a good dinner at the Veranda Restaurant. I don’t know whether there’s anything else in town worth seeing, hearing, or doing, but I have no doubt that I’ll catch another show at Florida Rep as soon as my schedule permits.

JANUARY 10 Back across Alligator Alley to the Fort Lauderdale Museum of Art (which for some eye-rollingly pretentious reason feels that it should call itself “Museum of Art | Fort Lauderdale”) to see “Coming of Age: American Art, 1850s to 1950s,” a touring show of seventy paintings and sculptures from the permanent collection of the Addison Gallery of American Art at Philips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts. Among the artists represented are John F. Peto, George Inness, John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, John Twachtman, Edward Hopper, John Marin, Stuart Davis, Arthur Dove, Charles Sheeler, Milton Avery, Jacob Lawrence, Hans Hofmann, Jackson Pollock, Joseph Cornell, and Josef Albers. Not all of the pieces are first rate, but this is one of those rare shows whose total effect is far greater than the sum of its parts. if somebody who knew nothing about modern American art asked me what it was like, I’d unhesitatingly send them to “Coming of Age.” (The catalogue is good, too.)

Dinner in Miami with Jordan Levin of the Miami Herald, an old friend, at Pacific Time, an ultra-trendy but excellent pan-Asian restaurant in the design district. Afterward we went to the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts, a postmodern cultural tabernacle where Miami City Ballet was dancing Paul Taylor’s Mercuric Tidings and George Balanchine’s Ballet Imperial.

It irked me no end to learn that the company would be dancing in New York while I was in San Diego and Kansas City, so I went online and saw that we could catch a performance on our last night in Florida. Mrs. T had never seen any Balanchine ballets, and this one, not surprisingly, knocked her for a loop.

(To be continued)

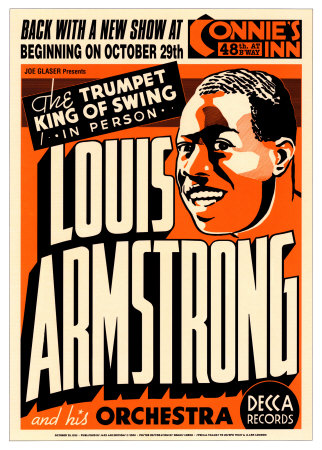

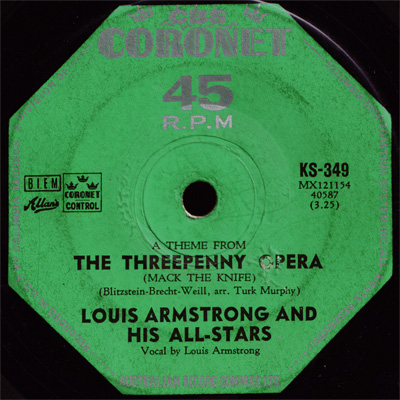

Asked whether he preferred the trumpet playing of Bobby Hackett or Billy Butterfield, Louis Armstrong thought it over and replied, “Bobby. He got more ingredients.” That’s one of my favorite Armstrong lines, and I like to think that it also applies to Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, my forthcoming biography of the greatest jazz musician of the twentieth century.

Asked whether he preferred the trumpet playing of Bobby Hackett or Billy Butterfield, Louis Armstrong thought it over and replied, “Bobby. He got more ingredients.” That’s one of my favorite Armstrong lines, and I like to think that it also applies to Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, my forthcoming biography of the greatest jazz musician of the twentieth century. • Department of corrections. Every book about Louis Armstrong published before 1999 contains numerous factual errors, some minor and others substantive. In that year Thomas Brothers edited Louis Armstrong, in His Own Words: Selected Writings, the first collection of Armstrong’s hitherto-unpublished autobiographical manuscripts and uncollected articles and correspondence and the first full-length book about Armstrong by an academic scholar.

• Department of corrections. Every book about Louis Armstrong published before 1999 contains numerous factual errors, some minor and others substantive. In that year Thomas Brothers edited Louis Armstrong, in His Own Words: Selected Writings, the first collection of Armstrong’s hitherto-unpublished autobiographical manuscripts and uncollected articles and correspondence and the first full-length book about Armstrong by an academic scholar. • Cultural context. Because Armstrong’s significance extends beyond the realm of jazz proper, I have sought at various points in Pops to place him in the larger world of art and culture. Here’s another excerpt from the fourth chapter, in which I talk about the relationship between Armstrong and Earl Hines:

• Cultural context. Because Armstrong’s significance extends beyond the realm of jazz proper, I have sought at various points in Pops to place him in the larger world of art and culture. Here’s another excerpt from the fourth chapter, in which I talk about the relationship between Armstrong and Earl Hines: I said my piece about America’s most popular painter

I said my piece about America’s most popular painter  A cross between “Three Sisters” and “The Glass Menagerie,” “Dancing at Lughnasa” is a semi-autobiographical memory play whose narrator (Chris Clavelli) tells what happened to his family during two summer days in 1936. Young Michael lives in a cottage with Chris (Rachel Burttram), his unmarried mother, and her four sisters, all of whom are barely making ends meet. The longings and frustrations of the Mundy sisters have grown too great to bear, and what was once a close-knit family is now–like Europe itself–on the verge of disintegration. The genius of “Dancing at Lughnasa” is that Mr. Friel has portrayed this sunset hour with the lightest of comic touches, letting the audience laugh as the black shadows that surround the Mundys grow imperceptibly longer.

A cross between “Three Sisters” and “The Glass Menagerie,” “Dancing at Lughnasa” is a semi-autobiographical memory play whose narrator (Chris Clavelli) tells what happened to his family during two summer days in 1936. Young Michael lives in a cottage with Chris (Rachel Burttram), his unmarried mother, and her four sisters, all of whom are barely making ends meet. The longings and frustrations of the Mundy sisters have grown too great to bear, and what was once a close-knit family is now–like Europe itself–on the verge of disintegration. The genius of “Dancing at Lughnasa” is that Mr. Friel has portrayed this sunset hour with the lightest of comic touches, letting the audience laugh as the black shadows that surround the Mundys grow imperceptibly longer.