As expected, the Washington Post has announced that Book World, its stand-alone book-review supplement, will publish its last issue on February 15. Thereafter the Post‘s book-related content will be integrated into the paper–but it will also be consolidated into a separate online section.

According to the New York Times:

Under the new arrangement at Book World, the combined pages allocated to books in the two sections will be equivalent to about 12 tabloid pages, down from the 16 published in the stand-alone section. The staff of Book World, already shrunk dramatically from its peak, will remain intact.

I’m sorry about that, but I must confess that the larger decision to kill off the print version means nothing to me, not because I don’t like Book World but because I read all newspapers (including the one for which I write) online. As far as I’m concerned, the fuss over this development is pointless, given that the magazine will continue to be available as a unified entity on the Post‘s Web site.

I’ve said it before, but it’s worth repeating: it is the destiny of serious arts journalism to migrate to the Web. This includes newspaper arts journalism. Most younger readers–as well as a considerable number of older ones, myself among them–have already made that leap. Why tear your hair because the Washington Post has decided to bow to the inevitable? The point is that the Post is still covering books, and the paper’s decision to continue to publish an online version of Book World strikes me as enlightened, so long as the online “magazine” is edited and designed in such a way as to retain a visual and stylistic identity of its own.

Newspapers are in trouble now because their editors and publishers have spent the past decade turning their faces from the inevitable effects of the coming of the Web. Writers would do well not to make the same mistake. So enough with the anguished kvetching already. Let’s turn loose of the past and see what we can make of the future.

* * *

Sarah Weinman’s take is here.

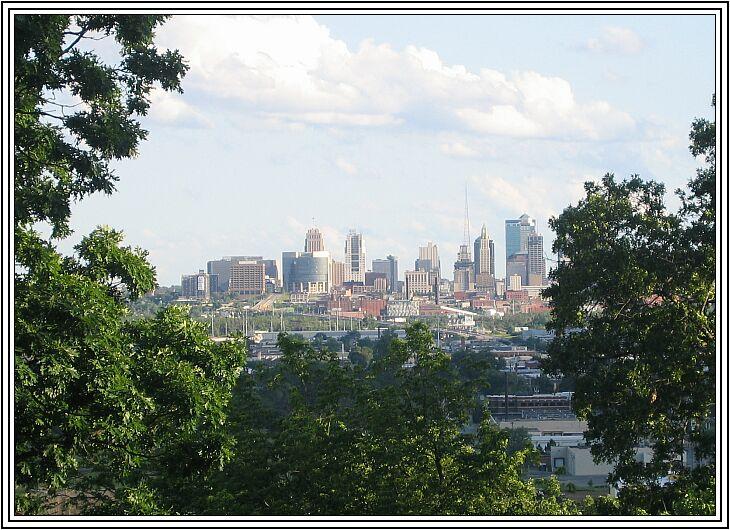

Kansas City, where I lived from 1975 to 1983, left a deep and indelible mark on me. I grew up in Smalltown, U.S.A., but Kansas City was the place where I went to college, rented my first apartment, played my first jazz gig, became a professional writer, and met the woman with whom I was to spend the first part of what I’m now old enough to call my middle years. For a time I took it for granted that I’d put down roots and raise a family there. But life, as is so often the case, had other plans for me, and when I left town and headed east, it was for good.

Kansas City, where I lived from 1975 to 1983, left a deep and indelible mark on me. I grew up in Smalltown, U.S.A., but Kansas City was the place where I went to college, rented my first apartment, played my first jazz gig, became a professional writer, and met the woman with whom I was to spend the first part of what I’m now old enough to call my middle years. For a time I took it for granted that I’d put down roots and raise a family there. But life, as is so often the case, had other plans for me, and when I left town and headed east, it was for good. I went to Kansas City to spend a day communing with myself when young, wondering whether I’d know where to look for him. I drove toward what sounded like a familiar address, took what seemed like a familiar exit, and promptly found myself in the middle of a city that looked nothing like the one I remembered. Where was Italian Gardens, the restaurant where I learned to love garlic? Where was the bank in which I’d worked after graduating from college? Both had been razed to the ground and replaced with shiny new buildings of whose existence I knew nothing. It felt as though I had awakened one morning, looked at my hand, and discovered that two of my fingers had vanished in the night.

I went to Kansas City to spend a day communing with myself when young, wondering whether I’d know where to look for him. I drove toward what sounded like a familiar address, took what seemed like a familiar exit, and promptly found myself in the middle of a city that looked nothing like the one I remembered. Where was Italian Gardens, the restaurant where I learned to love garlic? Where was the bank in which I’d worked after graduating from college? Both had been razed to the ground and replaced with shiny new buildings of whose existence I knew nothing. It felt as though I had awakened one morning, looked at my hand, and discovered that two of my fingers had vanished in the night. Many of my enduring memories of Kansas City have to do with food, a fact for which Calvin Trillin is to blame. In 1974 he published a book called

Many of my enduring memories of Kansas City have to do with food, a fact for which Calvin Trillin is to blame. In 1974 he published a book called  That moldering block is now the site of the

That moldering block is now the site of the  Relieved–but also unnerved. For Kansas City has changed so little that I found it all too easy to retrace my youthful steps. My first apartment? It’s still there. So is

Relieved–but also unnerved. For Kansas City has changed so little that I found it all too easy to retrace my youthful steps. My first apartment? It’s still there. So is  My last stop was the

My last stop was the