Paul Moravec and I went to the New York office of the Santa Fe Opera last week to get our first look at the set designs for The Letter. They were created by Hildegard Bechtler, who is currently represented on Broadway by The Seagull. Hildegard lives in Germany and does most of her work for European theaters, so Paul and I met her for the first time at the design presentation (as such occasions are called). Also on hand was Jonathan Kent, the director of The Letter, who lives in England and whom the two of us hadn’t seen for a year and a half. Jonathan and Hildegard, as is customary in theatrical projects, jointly worked out a visual interpretation of the opera, after which Hildegard created the finished design. They used my libretto as a point of departure, but from then on they were on their own.

Paul Moravec and I went to the New York office of the Santa Fe Opera last week to get our first look at the set designs for The Letter. They were created by Hildegard Bechtler, who is currently represented on Broadway by The Seagull. Hildegard lives in Germany and does most of her work for European theaters, so Paul and I met her for the first time at the design presentation (as such occasions are called). Also on hand was Jonathan Kent, the director of The Letter, who lives in England and whom the two of us hadn’t seen for a year and a half. Jonathan and Hildegard, as is customary in theatrical projects, jointly worked out a visual interpretation of the opera, after which Hildegard created the finished design. They used my libretto as a point of departure, but from then on they were on their own.

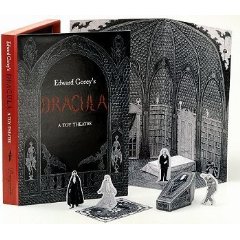

Once the introductions were out of the way, Paul and I rushed across the room to see what our far-flung collaborators had wrought. Sitting atop a grand piano was a scale model of the stage of the 2,100-seat Crosby Theatre inside which Hildegard had constructed a miniature version of the set for The Letter. It looked like a giant-sized doll’s house, right down to the tiny figures that represented the various characters. We gaped at the model, temporarily stunned into silence. I know how it feels to see the design for the dust jacket of a book that I’ve written, but that’s different: the cover is not the book. An opera, on the other hand, truly exists only in performance, and must be created anew each time it is produced: the score is not the show. As I saw how Hildegard had transformed my libretto into a three-dimensional object, a Biblical phrase popped into my mind: Thus the word was made as flesh.

The process of putting theatrical flesh on the musico-literary bones of The Letter is complicated further by the fact that the Crosby Theater is nothing like the old-fashioned Broadway theaters in which I spend so much of my working life as a critic. Not only does it have no proscenium arch or curtain, but the shape of the stage is decidedly out of the ordinary. Here’s how Paul Horpedahl, Santa Fe’s production director, describes it:

Our stage has side walls that are curved out, much like the shape of a speaker horn. Each of these walls is made up of six pairs of double doors for stage access. Additionally, there are sliding door panels at the back of the stage that allow for opening up to the landscape. The width of the stage at the apron is fifty-seven feet and narrows upstage at the back sliding doors to thirty-six feet. The depth to those doors is forty-one feet and the total depth to the scenery elevator is fifty feet. The ceiling above the stage is twenty-two feet at the doors and twenty-four feet at the apron. There is no fly tower and all lighting is hung up inside the ceiling so as not to be seen by the audience.

To put these numbers in perspective, the unusually large but otherwise traditional proscenium arch of the stage of the 3,800-seat Metropolitan Opera House is fifty-four feet square, while the American Airlines Theatre, the 740-seat Broadway house where the Roundabout Theatre Company is currently performing A Man for All Seasons, has a stage opening that is forty feet wide and twenty-five feet high.

To put these numbers in perspective, the unusually large but otherwise traditional proscenium arch of the stage of the 3,800-seat Metropolitan Opera House is fifty-four feet square, while the American Airlines Theatre, the 740-seat Broadway house where the Roundabout Theatre Company is currently performing A Man for All Seasons, has a stage opening that is forty feet wide and twenty-five feet high.

Because the Crosby Theater has no curtain, all scene changes take place in full view of the audience, and the absence of a fly tower means that backdrops and large set pieces cannot be shifted by “flying” them to and from the stage. This makes it a tricky space in which to present The Letter, which plays without interruption and takes place in five different locations:

• The living room of the jungle bungalow of Leslie and Robert Crosbie

• The Singapore law office of Howard Joyce, Leslie’s lawyer and Robert’s best friend

• Leslie’s jail cell

• The men’s bar of the Singapore Club

• The courtroom in which Leslie is on trial for murdering Geoff Hammond, her lover

But first-rate directors and designers like nothing better than to be asked to do the impossible, and Hildegard and Jonathan rose without apparent effort to the formidable challenge of creating a visual environment in which The Letter can be performed in such a way as to make dramatic sense to the viewer.

“Our goal was to create a cinematic design, one in which the action can move in a continuous flow,” Jonathan said at the start of the presentation. To this end, all five locations in the opera are portrayed on a single unit set consisting of two diagonally converging walls separated by an upstage opening. One wall, which is curved, consists of a series of louvered wooden doors. Except for a pair of non-identical doorways, the other wall is meant to look flat and solid–even though it isn’t. Both walls lend themselves to the shadowy film noir-style lighting that Paul and I have always envisioned as part of the “look” of The Letter.

Needless to say, there’s a lot more to the set than that, but I don’t want to give away any of Hildegard’s scenic surprises. Suffice it to say that in the nightmare world of The Letter, nothing is quite as it seems.

After Paul and I stopped babbling excited superlatives and pulled ourselves together, Jonathan and Hildegard walked us through the opera, demonstrating how the set will shift from scene to scene.  As they moved the set pieces and cardboard singers by hand, I felt as if the four of us were children playing with a freshly opened toy theater on Christmas morning. Of course we were engaged in a deadly serious job of work–we were, among other things, deciding how vast amounts of the Santa Fe Opera’s time and money would be spent on creating a theatrical illusion–but it didn’t feel anything like work.

As they moved the set pieces and cardboard singers by hand, I felt as if the four of us were children playing with a freshly opened toy theater on Christmas morning. Of course we were engaged in a deadly serious job of work–we were, among other things, deciding how vast amounts of the Santa Fe Opera’s time and money would be spent on creating a theatrical illusion–but it didn’t feel anything like work.

Jonathan asked us if we had any questions. Paul and I burst out laughing and high-fived each other. “I never imagined that it would look this beautiful,” I said. Then we rolled up our sleeves and immersed ourselves in the complicated business of settling on exact timings for the between-scene interludes. Since The Letter plays continuously from start to finish, Paul must compose orchestral interludes that will not only carry the audience from one scene to the next but also give the cast and crew sufficient time to change costumes and shift the set. Paul Horpedahl assured us that none of the scene changes would take longer than forty-five seconds to complete, but Jonathan estimated that we’d need a full minute to get from Leslie’s cell to the Singapore Club, so we decided to play it safe.

We would have been more than glad to spend the rest of the afternoon playing with our new friends and our new toy, but everyone had places to go, ourselves included, so at last we said our reluctant farewells. I bumped into Brad Woolbright, the Santa Fe Opera’s artistic administrator, as I was putting on my coat.

“I guess you guys might actually decide to go ahead and do our opera now, huh?” I said, trying in vain to keep a straight face.

“We’re giving it serious thought,” Brad replied without cracking a smile.

UPDATE: If you came here via Andrew Sullivan, you’ll want to read this.

I’m up in Connecticut with Mrs. T, doing as little as possible in between spells of overwork. We watched old movies all weekend, the best of which were Payment Deferred (not on video, alas),

I’m up in Connecticut with Mrs. T, doing as little as possible in between spells of overwork. We watched old movies all weekend, the best of which were Payment Deferred (not on video, alas),  Written by Jeff Hochhauser and Bob Johnston, “My Vaudeville Man!” is based on “Letters of a Hoofer to His Ma,” the epistolary autobiography of Jack Donahue, a real-life vaudevillian who ran away from home at the age of 17 to pursue a life on the wicked stage, much to the dismay of his mother, a hard-bitten Irish immigrant who took for granted that her son would go the way of his father, a ne’er-do-well drunkard. She was half right. Donahue became a Broadway star but died of alcoholism in 1930, leaving behind the short, sweet memoir from which Messrs. Hochhauser and Johnston have constructed this musical version of his youthful misadventures on the New England vaudeville circuit. The book is a neat piece of theatrical carpentry, the songs agreeable period pastiches that keep the action moving. Nothing very surprising ever happens, nor does it need to: “My Vaudeville Man!” is an uncomplicated crowd-pleaser that gets the job done with plenty of room to spare.

Written by Jeff Hochhauser and Bob Johnston, “My Vaudeville Man!” is based on “Letters of a Hoofer to His Ma,” the epistolary autobiography of Jack Donahue, a real-life vaudevillian who ran away from home at the age of 17 to pursue a life on the wicked stage, much to the dismay of his mother, a hard-bitten Irish immigrant who took for granted that her son would go the way of his father, a ne’er-do-well drunkard. She was half right. Donahue became a Broadway star but died of alcoholism in 1930, leaving behind the short, sweet memoir from which Messrs. Hochhauser and Johnston have constructed this musical version of his youthful misadventures on the New England vaudeville circuit. The book is a neat piece of theatrical carpentry, the songs agreeable period pastiches that keep the action moving. Nothing very surprising ever happens, nor does it need to: “My Vaudeville Man!” is an uncomplicated crowd-pleaser that gets the job done with plenty of room to spare. With the financial crunch hitting New York producers where it hurts, I’ve written a “Sightings” column about high-quality small-cast plays that either never made it to Broadway or, like The Voice of the Turtle, haven’t been seen there for decades. Pick up a copy of tomorrow’s Wall Street Journal and you’ll find an annotated list of five such plays, all of which (A) can be produced cheaply and (B) lend themselves to the celebrity casting without which it is no longer possible to open a straight play on Broadway.

With the financial crunch hitting New York producers where it hurts, I’ve written a “Sightings” column about high-quality small-cast plays that either never made it to Broadway or, like The Voice of the Turtle, haven’t been seen there for decades. Pick up a copy of tomorrow’s Wall Street Journal and you’ll find an annotated list of five such plays, all of which (A) can be produced cheaply and (B) lend themselves to the celebrity casting without which it is no longer possible to open a straight play on Broadway.