Susan Marshall & Company / BAM Harvey Theater, New York City / October 21-25, 2003

In our current climate of branding, dance concerts must have titles.

The choreographer Susan Marshall, already branded as a genius by her copping a MacArthur Fellowship 2000, slyly called her latest program, part of BAM’s Next Wave series, Sleeping Beauty and Other Stories. The words on both sides of the (pointedly unitalicized) “and” are simply the names of her two newest works. The first is one of the finest efforts of her career.

Like the landmark Marshall pieces Interior With Seven Figures (1988) and Arms (1984), Sleeping Beauty, while pretending to be abstract, evokes the poignancy of the human condition. It takes as a given the darkness in which we all operate, acknowledges the basic futility of human relationships, yet charts (and celebrates, I think) the persistence with which we doggedly continue trying to make them work—as if our identity depended upon the hope-fueled effort. All of this is done so unemphatically, with so much sheerly visual gratification along the way, you hardly know what’s happening to you until the piece ends and your emotional experience has been so profound, you can barely move or speak.

For Sleeping Beauty, Douglas Stein has provided a stern beauty of a set. Multi-paned crackle-glass panels partition the space, creating an open field framed by semi-private corridors. Through the panes, tiny windows offering different degrees of translucency, both dancers and viewers can see variously—fully, partly, or not at all. Huge work lights hang high above the dancing ground, suggesting, despite the austerity of environment, the chandeliers Perrault might have given Aurora’s palace. The scene is subtly and eloquently lighted by Mark Stanley (who surely deserves a MacArthur of his own).

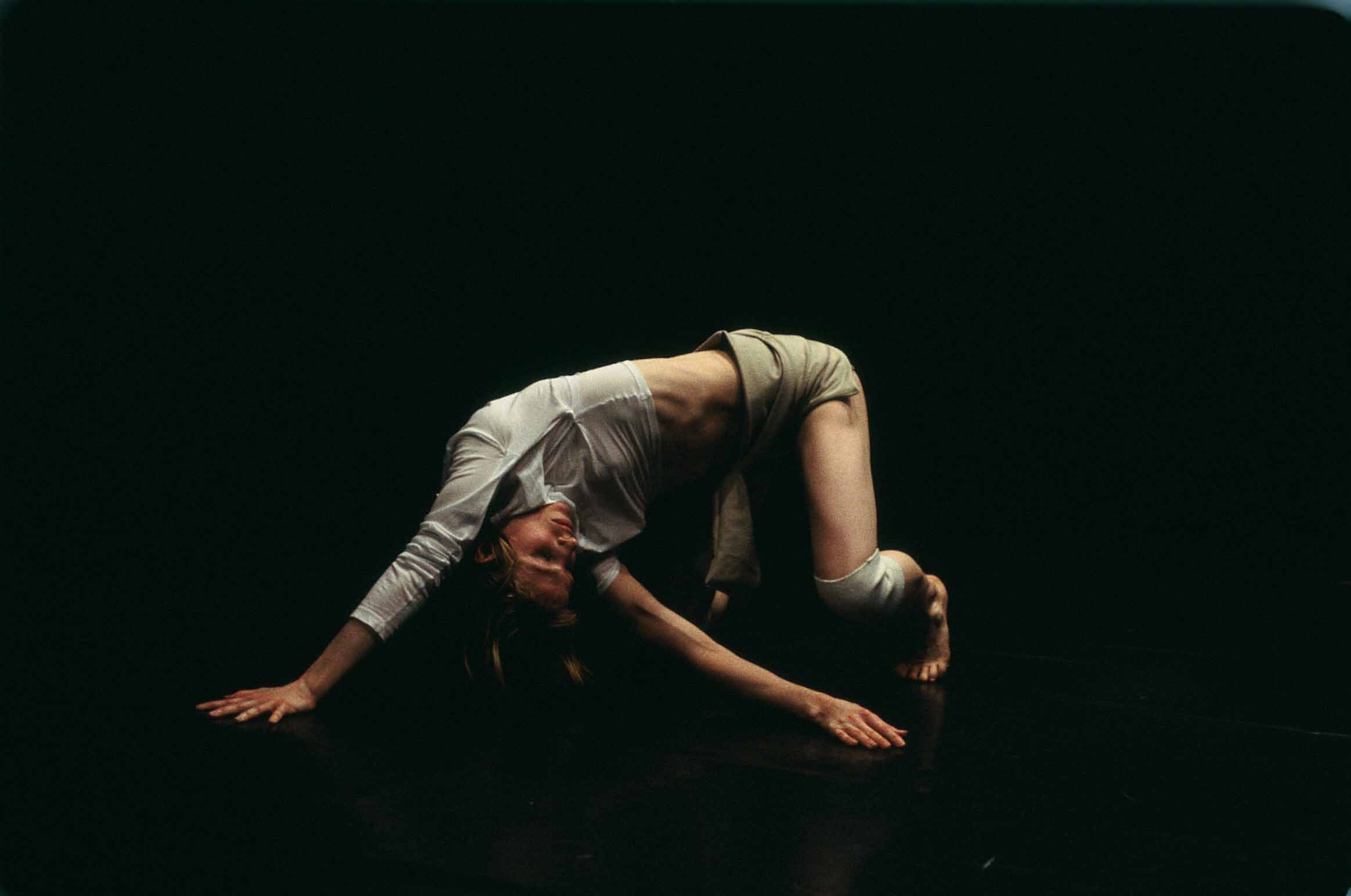

The focal point of the choreography is a young woman, the pale, grave-faced, Kristin Hollinsworth, distinguished for her long-limbed flexibility and grace. Surrounding her is the small crowd one might call family or society. Movement motifs define the girl’s difference and strangeness: Her arms and legs stretch, oddly angled, as if to shield her from view or point to a faraway nowhere; her whole body, held off-kilter, falls into fits of stasis as if she were absorbed in a dream. She is luminous in her isolation, and inscrutable. (Doesn’t this lie at the heart of being a princess—remaining aloof and apart from the ordinary run of humankind?) The crowd insists upon making her one of them.

The focal point of the choreography is a young woman, the pale, grave-faced, Kristin Hollinsworth, distinguished for her long-limbed flexibility and grace. Surrounding her is the small crowd one might call family or society. Movement motifs define the girl’s difference and strangeness: Her arms and legs stretch, oddly angled, as if to shield her from view or point to a faraway nowhere; her whole body, held off-kilter, falls into fits of stasis as if she were absorbed in a dream. She is luminous in her isolation, and inscrutable. (Doesn’t this lie at the heart of being a princess—remaining aloof and apart from the ordinary run of humankind?) The crowd insists upon making her one of them.

Together the two camps, Herself and The Others, perform the activities of rehabilitation. Again and again, the girl’s often unresponsive body is positioned into the anatomical positions that mean contact (even the small interactions so-called normal folks take for granted), communication, lust and its aristocratic cousin, love. Occasionally the girl initiates the exercises herself; sometimes her would-be rescuers, losing patience, bully her into the process; otherwise the action, even when physically fraught, exudes a clinical serenity. Whatever the emotional atmosphere, the result is always the same. The girl’s body halts; passive and flaccid, it drops from her would-be helpers’ arms. As both sides give up for the moment, the girl moves away with an air of a hurt bafflement, retreating into her chamber of living death. (Once in a while, though, there’s a flicker of stubbornness about her response, a glimpse of the madman’s will to persist in his madness because it constitutes his only security.) Inevitably, heroically, both sides keep coming back for another go.

The saddest thing about the circumstances Marshall depicts is that the afflicted girl seems (though only seems, and only intermittently) to want to join in the flow of common life, to be part of a social world, to connect. But, despite repeated effort, both heartbreaking and exasperating in its futility, she can’t—and both she and the people concerned with her plight are doomed to not knowing why. Or is the saddest thing, after all, the fact that, increasingly as the piece progresses, the crowd reveals itself to be simply a collection of people like the girl, the difference in their condition being merely one of degree, not kind? In the closing image, both heroine and nameless crowd, the ostensibly maimed and the ostensibly whole, lie outstretched on the ground, rolling back and forth in a horizontal line, like wind-whipped ocean waves in an eternity of sameness.

Other Stories, the companion piece to Sleeping Beauty, is dutifully joined to its partner on the program by its opening image: a woman’s body lying supine on a raised plinth, illuminated by a glaring shaft of light on an otherwise dark stage. But the piece quickly moves on to its own concerns, revealing, in edgily fragmented sightings, seven hyperactive characters in search of an auteur to provide them with one of drama’s basic necessities: narrative—or at least dilemma, or at the very least situation.

As it is, they’re merely fugitives from the stage that is perennially set for dreams when we sleep, or perhaps the lurid personae that spring from the synthetic sleep of anesthesia (think of the old term “operating theater”), or souls lost in the outtakes of a movie doomed to failure from the start. Their antics—shards of high (melo)drama, surreal opera, and vaudeville, along with the frantic chaos invariably attendant on theatrical enterprises—seem to go on for a century, gradually relinquishing their right to our attention. I think the piece is supposed to be funny, and the opening night audience did chortle cooperatively a few times, but Marshall, who has a look of Garbo about her, doesn’t laugh with confidence or ease.

The one terrific thing about Other Stories is the costuming, by Kasia Walicka Maimone, who has served Marshall long and well, but usually, as in Sleeping Beauty with subdued lyricism. Here the costumes are a medley of wildly fanciful finery borrowed from the worlds of princess, slut, and itinerant entertainer—garb for a poetic Hallowe’en.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

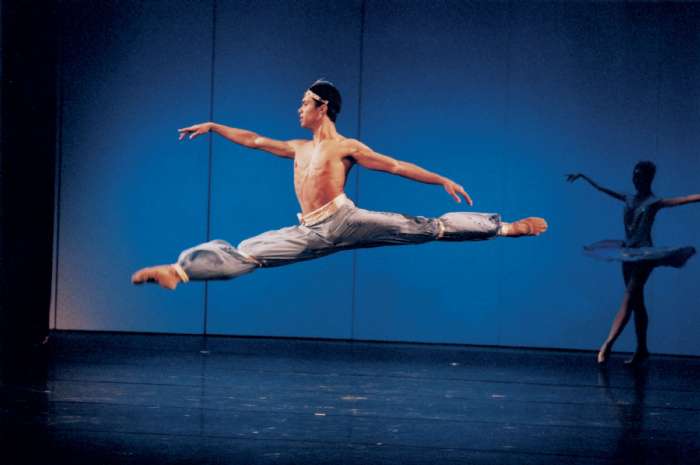

His performance was ardent. Passion for the sheer physical experience of the bravura choreography was fused with a vivid—indeed, blazing—idea of character and situation. It was evident immediately that this guy is a creature of the stage. His energy is extravagant. His technical ability in the big moves—-the huge, powerful leaps, the multiple turns coupling speed with control—is formidable. He grabs space the way a street gang carves out its territory, but he’s never strained or sloppy about it. Launched into the air, his body remains perfectly composed, as if suspended in time as well as place, creating an indelible image. He retains the rawness and wildness of a kid left to grow up on his own. This is balanced, somewhat eerily, with mature self-possession and authority. You look at him and think: This is why I watch dancing. This is the real thing.

His performance was ardent. Passion for the sheer physical experience of the bravura choreography was fused with a vivid—indeed, blazing—idea of character and situation. It was evident immediately that this guy is a creature of the stage. His energy is extravagant. His technical ability in the big moves—-the huge, powerful leaps, the multiple turns coupling speed with control—is formidable. He grabs space the way a street gang carves out its territory, but he’s never strained or sloppy about it. Launched into the air, his body remains perfectly composed, as if suspended in time as well as place, creating an indelible image. He retains the rawness and wildness of a kid left to grow up on his own. This is balanced, somewhat eerily, with mature self-possession and authority. You look at him and think: This is why I watch dancing. This is the real thing. Here’s where you find out, perhaps, more than you want to know, more than you should know. Usually the best thing about an artist is his art. Yet we can’t help being curious.

Here’s where you find out, perhaps, more than you want to know, more than you should know. Usually the best thing about an artist is his art. Yet we can’t help being curious.

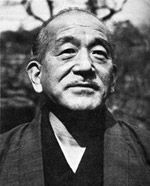

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing – an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period – extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties – once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing – an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period – extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties – once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)