In comments, Ernest asks (and I’d rather address this than the article I’m supposed to be writing today):

I was always

curious about what a student could do if their professors genuinely dislike the

music they create. It seems like a giant imposition on the student to alter his

style just to fit his or her teacher’s expectation of good music. Is this at

least expected of the student in so far as the course is concerned? I don’t

want to seem like I think this is the norm, but there has to have been

overzealous teachers who try to discourage them into writing more traditional

pieces, right?

Others will undoubtedly want to weigh in on this. I want to say I’ve never disliked a work by one of my students, though I have to admit it’s not quite true. I’ve rarely completely liked one, either. When you watch a piece grow from its first inchoate ideas to some sort of performable score, you get, I think, more caught up with the process than the result. This is a strange and mysterious process with two egos involved, and your own is not the important one. I would never, ever tell a student that the overall effect he or she wants to create is of no value. I always feel most satisfied when I can pinpoint localized things in the piece that I think injure the whole shape or progress of the piece, and the student, in response, ignores my proposed solutions but takes the criticism seriously and comes up with his or her own revisions instead. That satisfies my sense of having made a difference, and the student’s sense of having come up with every note. And to this extent, liking or disliking the piece, or its style, is beside the point. It may be a little like asking a gynecologist whether his last patient was pretty.Â

That said, in my situation, I’m the number 2 or 3 composition teacher at Bard, and so any sensible student who’s going to write music in a style I don’t care for is much better off studying with Joan Tower, whose tastes are the diametric opposite of mine and who can do much more for him professionally after graduation than I can. Joan seems to send me the students she gets whose music is “too tonal” or too deliberately uneventful. This is why I think it’s so crucial that a music department aim for diversity of viewpoint among its faculty, which many refuse to do. I think to find an idiom that neither Joan, George Tsontakis, nor I would be sympathetic to, you’d pretty much have to be a staunch Ferneyhough acolyte, which is not common among undergrads. It’s rare, in fact, for our undergrad composers to have much sense of style at all – their music is more often made up (as mine was at that age) of bits of this and that: a harmony they liked in Steve Reich, a melodic tic from George Crumb, some glissandos they heard in Penderecki. Now, I’ve never taught graduate composition students, and the few who’ve brought me their music have done so, as you can imagine, because it’s in a style that they think is right up my alley (often coming to me because their own professors weren’t sympathetic). If an accomplished 24-year-old composer brought me music conditioned by her passionate admiration of, say, Chris Rouse or Harrison Birtwistle, I’d have a quandary I haven’t faced yet. I’ve never regretted teaching in an undergrad-only institution.

But when I haven’t much liked hearing a piece by one of my students, it’s usually with a feeling that “This student isn’t much interested in the same things I am” – which is fine, because few of them are. And of course I would never grade them downward for that, because all that interests me grade-wise is how much work they put in – and that work can even be a lot of serious thinking and sketching, with little actual music to show for it. One of the smartest students I ever had used to analyze scores by prize-winning young composers and try to imitate them – certainly not a route I encouraged, but I watched him with amusement and added what suggestions I could. I gather that, in grad school, he eventually found that a dead end, but it wasn’t in his interests for me to predict that. My teaching motto is from Blake: “If the fool would persist in his folly, he would become wise.”

There are a lot of composers who feel that a student should try out every composition teacher in the department to get a variety of viewpoints, but I was never very sympathetic to that. Some of our students do it, and if they go back to Joan or George (or our excellent jazz composition teacher Erica Lindsay) I wish them well and continue to take an interest in their progress. I was the type of young composer who would not have benefitted from a stylistically adversarial relationship – and didn’t, the couple of times it happened. (I had one abominable professor who acted so insulted when I suggested trying another teacher that I was afraid to switch. He was a horse’s ass, and should have been fired, but instead made students miserable for several decades.) But I do think that the type of composition teacher who insists on the student writing in his or her own style  – not nearly as common as they used to be in the ’60s and ’70s, apparently – is very much to be regretted, and I think most composers of my generation have realized the harmful effects of that. Anyone disagree?

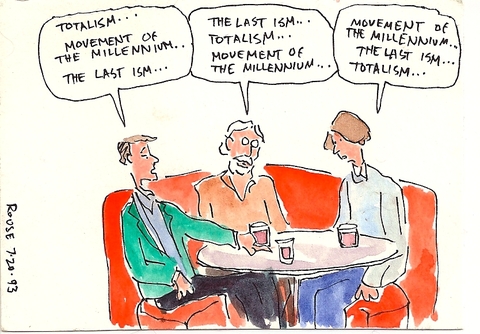

And to return the original question to its original context in connection with the minimalism conference: if the musicologists at Bard wanted to hold a serialism or Spectralism conference, or one on the New Romanticism or New Complexity, I would find that interesting rather than threatening, and would probably attend some of it with a curious attitude. My compositional motto comes from Satie: “Show me something new, and I’ll start all over again.”