Probably no one but me gives a damn whether John Luther Adams’s music is postminimalist or totalist. As far as the specific terms go, I don’t give a damn either. But when I started surveying, in the 1980s, all the music that passed through New York (and, via recording, the rest of the country as well), I couldn’t help but notice that, among composers who were continuing and developing the minimalist aesthetic, there were two groups of qualities that almost always went together. The composers whose music was based on a steady beat virtually throughout, usually an 8th- or 16-th note pulse, also tended to use diatonic tonality, quasi-minimalist structures like additive process or permutation, mostly quiet dynamics, and acoustic timbres augmented by the occasional synthesizer. Those who used competing tempos, either simultaneously or interlocked somehow, tended to use more dissonant sonorities, more global large-scale rhythmic structures, mostly loud dynamics, and amplified or electric instruments such as guitars. For the former I appropriated the already-current but undefined word postminimalism; for the other the word totalism was provided. The distinction between the two styles was so striking and consistent that it would have seemed capriciously anti-intellectual, an act of scholarly irresponsibility, to have neglected to articulate my observations. Yet, judging from the comments I’ve received in subsequent years, the vast majority of musicians wish I had done exactly that: leave my musicological data on the ground where I found it.

Very few composers wrote music that combined different qualities from those two styles, but one major one who did was John Luther Adams. More often than not his tonality is diatonic, using a seven-note scale (often the “white†notes) with no pitch ever given precedence. Yet some of his pieces, like Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing and his piano cluster piece Among Red Mountains, have proved that he is just as happy to use the entire chromatic spectrum and a maximum of dissonance. His music for pitched instruments is almost always soft; his percussion music is mostly fortissimo. Nominally, his music falls square in the totalist camp because it almost always layers different tempos together. But some of John’s implied tempos are very slow, giving a new pulse only every 10 or 15 seconds, so that the effect seems more postminimalist, without the gear-shifting surface complexity you find in much totalist music. Even when he has 4-against-5-against-6-against-7 in each measure, the effect – achieved pianissimo with mallet percussion, celeste, and harp – is not so much one of tempo contrasts as of indistinct clouds of notes. No other composer from the minimalist tradition so resists being pulled into one definition or the other.

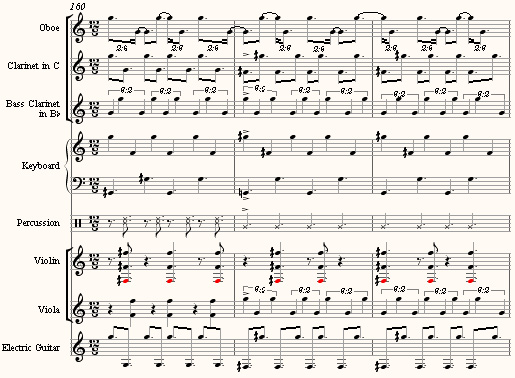

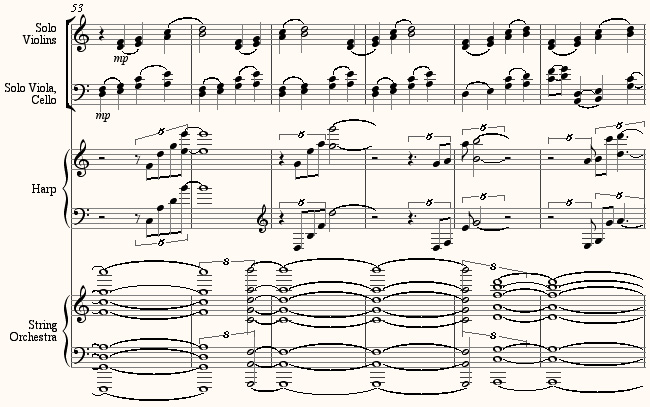

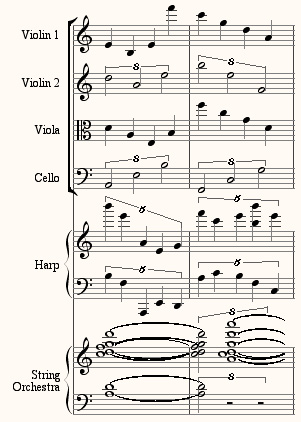

Dream in White on White (1992) has been surpassed in its ambitions by many of John’s works, but it became a prototype for one side of his ouput, and was a watershed in his development. Scored for string quartet, harp, and string orchestra, the piece opens with the string orchestra playing seven-note chords, changing to a new one every 2 and 2/3 measures. The solo quartet enters with chords changing every two measures, for a slow 3:4 rhythm. The harp then enters in four-note phrases in quintuplets, a new phrase every 1 and 3/5 measures. Thus the phrase rhythm is 20:15:12 by duration, or 3:4:5 by tempo, coming back in phase every 8 measures. At measure 53, the string quartet launches into what is marked as the “Lost Chorales,†outlining out-of-phase 4- and 5-beat loops between the two violins versus viola and cello. You can see those relationships, against the recurring harp and string orchestra pulses, in this example:

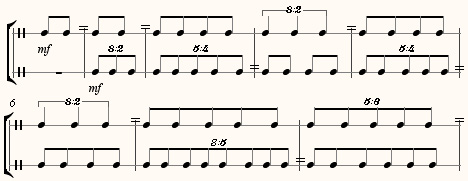

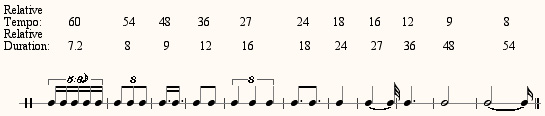

The next section has plucked notes in the quartet and harp outlining faster 3:4:5 rhythms in each measure, over a chord periodicity of 1 and 1/3 measures in the orchestra:

The chorales return, the string orchestra’s tempo increases, but in a final section the original tempo relationships resume.

You can hear Dream in White on White here. The work’s template has become the basis for at least two much larger works by Adams (and two of my favorites), Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing and In the White Silence. In the White Silence is in fact a magnificent expansion of Dream in White on White, stretched out to 75 minutes and with lovely solo lines for the quartet members. Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing achieves much denser clouds using mallet percussion and the entire chromatic scale. In each of these a large-scale process, implicit in Dream in White on White, is carried out more rigorously: an slow, stepped expansion of melodic intervals from 2nds through 3rds, 4ths, and on up to 7ths. (I kid John that when I start hearing tritones in his music, I know the piece is half over.) More aggressive aspects of totalism appear in John’s drum music, which hammers out more obvious intricacies at a more virtuoso tempo; but that’s for another day.