The holidays are the best of times and the worst of times for hearing music in New York City. Hosting friends and family, or being a guest on a visit, is great, until it pales. That’s when we look for entertainment options, and going out for jazz seems like the most sociable, something-for-everybody activity. The […]

Archives for 2011

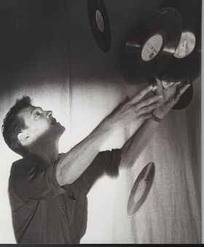

Turntablism — avant noise or early music?

Onstage at the Japan Society before concertizing with Otomo Yoshihide, Christian Marclay told a crowd, “You’re going to see us do some things you’ll think are interesting, but you have to understand how shocking it was to do this in the ’80s, when people treated records as something precious.” And thereby Marclay, famous recently for […]

Shemekia Copeland roils Jazz at Lincoln Center with roadhouse blues

A blues-belter with a beautiful big voice and cred in the rockin’, bawdy, electric tradition, Shemekia Copelandbrought a funky good time to the elegant Allen Room of Jazz at Lincoln Center last Thursday night (and probably Friday, too), backed by a a tight four-man band, carrying a slew of fresh and catchy songs. It’s unusual […]

Iraq vet and New Orleans avant-gardist WATIV on first visit to NYC

Composer and improvising keyboardist William “WATIV” Thompson — Mississippi-born, New Orleans-based and an Iraq war veteran who I profiled for NPR in 2005 (podcast below) when he was posting laptop computer music he created in Bagdad during free time from his counterintelligence duties – made his first visit to New York City last week. I met him […]

West Side Story @ 50 — the soundtrack’s the thing

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of West Side Story — the movie, released October 18 1961, Â not the play which debuted on Broadway in 1957 — for my column in CityArts – New York, I listened to the Bernstein/Sondheim music in many variations. Here’s my report, slightly revised for the web: For West Side Story, the […]

Marian McPartland choses “Piano Jazz” successor: Jon Weber

Pianist and NPR “Piano Jazz” host Marian McPartland, age 93, has found a worthy successor to her post interviewing and duetting with musicians — Jon Weber, an extraordinarily fluent keyboard artist with encyclopedia depth on many of the earliest styles of American improvised music. Though rather under-recorded, Jon excels at the most intricate (and […]

Bennie Maupin talks to me

Reedist Bennie Maupin, whom I interviewed in the Jazz Talk Tent at the Detroit Jazz Festival in 2006, says “One thing about Detroit, you learn how to make money.” Another thing he recalls from his youth: “There’s a lot of noise here because of the factories, and early on I listened to things that were basically […]

MC to stars @ Jazz Foundation Loft Party benefit

MC JazzMandel: At the Jazz Foundation of America’s Benefit Loft Party tonight (Oct. 29), 7 pm to midnight, Manhattan, my room has — Tom Harrell‘s Quintet, pianist Marc Marc Cary, preeminent bassist Ron Carter with fine guitarist Gene Bertoncini, turbanated organist Dr. Lonnie Smith with alto sax/Mardi Gras Indian Donald Harrison and N.O. drummer Herlin Riley (yeah!), magisterial Randy Weston’s African Rhythm Quintet, […]

Marilyn Crispell’s “private” solo piano web-tv concert

Marilyn Crispell is an improvising pianist of deep concentration and beautiful touch, who at 7:30 pm EDT tonight (Thursday, Oct 27) offers at modest cost a “private” solo concert, the webcast of a three-camera shoot, from a soundstage near her residence in Woodstock NY. This is the first I’ve heard of a jazz-related performer performing […]

Surprise: Birth and re-birth of jazz journalism outlets

Double-barrelled rare upbeat jazz news: The husband-wife team behind publicists Improvised Communications (plus a couple helpers) launch JazzDIY.com, an online “trade journal for jazz” And a composer-improviser from Oregon saves Cadence magazine, founded in 1976, from demise. Scott Menhinick and his wife Jennifer Peabody are doin’ it themselves and hoping to share information on jazz […]

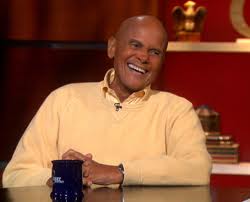

Don’t laugh at Harry Belafonte (laugh with him)

Don’t laugh at Harry Belafonte, the incomparable American/world roots folk musician and popularizer, for being caught on tv asleep or meditating last week. Laugh with him during his appearance with Steven Colbert which he amazingly turns into a genuinely musical  and touching duet on “Jamaican Sunrise.” Even Colbert gives it up to Belafonte, whose wit is quick. Indeed, at age 84 the […]

Jazz Audience Initiative study posted, webinar set

The Jazz Audience Initiative, a 21-month research project of Columbus, Ohio’s Jazz Arts Group, has posted its final reports and scheduled a webinar for October 21 (free registration available) to discuss them. Among the main points: Musical tastes are socially transmitted. Jazz has relatively diverse audiences. People pay to hear specific artists. Local programming shapes […]

Jim O’Neal, Living Blues founder, ill and uninsured

Jim O’Neal, founder in 1970 of Living Blues magazine and a serious independent researcher into American roots music, is among the 59 million Americans without health insurance, and has lymph cancer. A series of benefit concerts are scheduled to raise funds for his treatments and a fund has been set up at Commerce Bank in […]