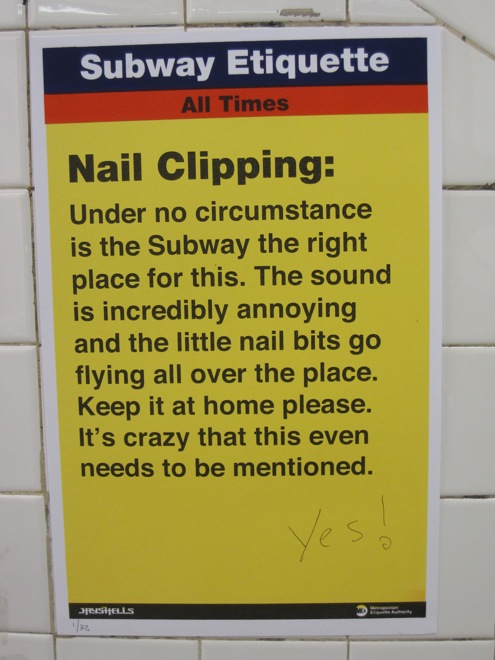

Or a contender, anyway. It's in the subway at 14th Street and Eighth Avenue, disguised as an official Metropolitan Transportation Authority notice -- except that the MTA generally doesn't do numbered screen prints. Artist Jason Shelowitz does.

On this poster, evidently part of a campaign he's waging (of which I knew nothing until I saw the sign this evening and burst out laughing), Shelowitz has replaced the customary MTA logo, in the lower right-hand corner, with one for the MEA; the "E," of course, stands for "etiquette."

His etiquette rant may not be in the official style of the MTA, but it's definitely in the style of a conductor or two. It will have a lot of people who've been creeped out by their fellow subway riders saying, "Hear, hear." Or, as someone's already scrawled on this poster: "Yes!"

It was the kind of spring day, sun-kissed and warm, when frigid winter seemed vanquished, yet the fetid New York City summer felt safely far off. Flowers were bursting out, early, all over town.

As frequently happens when hibernation comes to an end, a craving to eat something healthy and green developed. Off I went then, down West 13th Street to Integral Yoga Natural Foods, with no suspicion that poetry was waiting to ambush me.

But there beneath the strawberries, just above the honey tangerines, dangled a text as romantic as the day: William Blake's "The Tyger," printed and laminated like the signs around it, and spattered with water droplets from the automatic misters.

Verse, lurking amid the greenery! As a spirit-lifting surprise, it was astonishingly potent. Curious and smiling, I accosted the first employee I saw, in a neighboring aisle, to ask what it was doing there. The man said he didn't know; he hadn't seen it yet, but he guessed his boss had put it up: a variation on the cartoon characters that sometimes decorate notices there. A couple of minutes later, he walked over to read it. "William Blake," he murmured, though the sign didn't say so.

I wandered off, cheerful, and burbled to the cashier that there was poetry in the produce section. "Does it have something to do with produce?" she asked. A reasonable question. That the answer is no -- that the poem is simply there, not there to sell us blueberries -- has nearly everything to do with its power to jolt us gently into joy.

"I don't want to sound self-important on behalf of my colleagues, but we feel that in the scheme of things -- coverage of the arts in the UK -- we are doing something of genuine value. We are aiming to provide overnight reviews which people can read before anything they'll find in any of the print media. And those reviews will almost always be longer and more in-depth. And in the case of one or two of the online counterparts of rival newspapers, they will be better subbed and edited and have way fewer typos. (Which sort of matters to us.)"

That's Jasper Rees of The Arts Desk, a new, "professionally produced arts critical website" launched by a London collective of accomplished arts journalists after the Daily Telegraph halved its arts budget. In a Q&A with me on ARTicles, Rees discusses the site and how a non-hierarchical arts publication works.

Quinn Dombrowski went to the University of Chicago because Quinn Dombrowski is a great big giant nerd. She is cheerfully geeky, insistently nerdy. Quinn Dombrowski is such a huge nerd she frets that the University of Chicago is becoming too social -- that the university has been gently cultivating a more well-adjusted, outgoing student body, which clashes with its famously studious reputation, which is why she went there to begin with. She has been worrying a lot about this lately. For the past two years she has made a quiet project of studying graffiti at the Regenstein Library, the school's largest library, and during that time she has noticed an increase in fraternity and sorority letters scrawled into its pale walls and wooden carrels.

The biggest challenge: shifting from telling a story that's read to one that's heard or watched. Radio is a much more intimate and conversational form of storytelling, a voice in your ear. With radio and television and our Web videos, we're learning to resist the urge to "explain" and let the visuals and audio do the talking. Sounds simple enough but to folks who've been writing for the page for years, it can sometimes feel like putting your pants on inside out.

The relentlessly changing metropolis is a story as old as New York, and the basic narrative of the Ohio Theatre drama -- about how gentrification makes it difficult for artists to remain in once-seedy neighborhoods that they helped to make safer and more attractive -- plays out in cities across the country. Still, it's worth pausing to consider, in the theater's final six months, what will be lost with its passing.

If you listen to NPR's "Morning Edition" in a loop, catching the end of the show before you hear the beginning, today's program would have brought you a story on Andrew Lloyd Webber's sequel to "The Phantom of the Opera," complete with comments from its West End director, Jack O'Brien.

A while later, at the top of the show, you'd have been forgiven for thinking -- if your attention had wandered, or you'd been multitasking -- that they were already rerunning the same story, or another one on the same subject. "Standing near the back of the audience, Jack O'Brien would occasionally shout out his disapproval," reporter Don Gonyea intoned, and you might have imagined the three-time Tony Award winner at a tech, getting boisterous with his team.

Then Gonyea finished his sentence -- "once even causing the president to pause, briefly" -- and you might have thought, distractedly, "What's this? Obama's at a tech rehearsal?" But, no, this Jack O'Brien turns out to be a self-employed electrician who opposes the Democrats' health care legislation "because he believes it will use federal dollars to help cover abortions," and because he thinks the country can't afford the price tag. And Obama was at a university in Pennsylvania, not a theater in London.

Ah. That explains it.

ARTicles, the recently dormant blog of the National Arts Journalism Program, comes back to life today with an excellent, much-expanded group of bloggers: Sasha Anawalt, MJ Andersen, Alicia Anstead, Laura Bleiberg, Larry Blumenfeld, Jeanne Carstensen, Robert Christgau, Thomas Conner, Lily Tung Crystal, Richard Goldstein, Patti Hartigan, Glenn Kenny, Wendy Lesser, Joe Levy, Ruth Lopez, Nancy Malitz, Douglas McLennan, Tom Moon, Abe Peck, Peter Plagens, John Rockwell, Patrick J. Smith, Werner Trieschmann, Lesley Valdes, Douglas Wolk and me.

Already up today are posts by Robert Christgau (on Robert Forster's criticism and on sportswriting as cultural journalism), Wendy Lesser (on the beauty of small music venues), and me. It's worth taking a look.

Update: There are fresh posts, too, by Larry Blumenfeld (on the morphing of "alternative" spaces), Richard Goldstein (on jazz manouche in Paris) and Peter Plagens (on the link between Holden Caulfield and Andy Warhol).

Talking lima beans turned Lynn Nottage into a playwright -- or they helped, anyway. Without "Succotash on Ice," the children's play she saw as a small girl the very first time she remembers going to the theater, there might not have been a "Ruined."

Talking lima beans turned Lynn Nottage into a playwright -- or they helped, anyway. Without "Succotash on Ice," the children's play she saw as a small girl the very first time she remembers going to the theater, there might not have been a "Ruined."In the stories we tell about ourselves, the temptation to lie -- to ourselves, to each other -- triumphs more often than it ought to. It happens in public life (see John Edwards), in pulp fiction masquerading as memoir (see James Frey), and in the cultural myths we accept as true (see New Yorkers' entrenched and baseless insistence that they're tougher than the average bear). This is nothing new.

And yet: Is it getting worse? Is a devolution in our use of language helping to blur the distinction between truth and untruth?

"Reality itself is a term that is rapidly being devalued," Daniel Mendelsohn writes in The New Yorker. Pondering the mendacity that has long been entrenched in the memoir genre, he points to the dominance of reality TV as emblematic of this cultural moment, when the degree of "blurring between reality and fiction" seems especially high.

Reality's root, too, is taking a beating. A lot of us don't even know what "real" means anymore, and the confusion is polluting our politics. The 2008 presidential campaign pitted a place called "real America," populated by "real Americans," against ... well, against a bunch of fake Americans living in fake America, apparently. Who knew that the simple act of opposing a Republican could invalidate a passport, a birth certificate, the results of a citizenship test?

Last Sunday, when President Obama flew to Massachusetts to try to salvage Martha Coakley's Senate run, Scott Brown's supporters flocked to a rally of their own. "The president may be in Boston," read a block-lettered sign in the crowd, "but the real people of Mass. are here with Scott Brown in Worcester." The phrase "real people" was, predictably, written in red.

The sign laid out a clear dichotomy, and a false one, casting Obama and his supporters as fake people (cyborgs? foreigners? carpetbaggers? all of the above?) and those on Brown's side -- the Right's side -- as authentic.

"Authentic": another word whose meaning seems now to elude us.

A few years ago, a young artist I know put up a website to sell the clothes she'd designed. Outlining her personal narrative in her bio, she strained to establish blue-collar cred: not an easy task, given her upper-middle-class upbringing, but reality didn't make as good a story. So, instead of crediting her love of design to her mother's creative passion for sewing, she twisted the truth to suggest that her mom (who was, in fact, a doctor's wife) was a seamstress. It sounded, you know, more authentic, what with the struggle and all.

When the drama that makes a compelling story is missing from lived experience, we're only too eager to fabricate it, or have it fabricated for us. But, as Mendelsohn writes, "an immoderate yearning for stories that end satisfyingly -- what William Dean Howells once described to Edith Wharton as the American taste for 'a tragedy with a happy ending' -- makes us vulnerable to frauds and con men peddling pat uplift."

Here's the thing: We can tell whatever tales we want to, but make-believe is still make-believe, illusions are still illusions, and lies are still lies. In failing to insist on those distinctions, we engineer our own continuing gullibility.

When we lose control of a simple word like "real," when we accept its widespread dishonest misuse, we lose sight of what's genuine. If there's no true north, how are we supposed to find our way?

Producing real journalism, good journalism, costs real money. Charging for frequent online access, as The New York Times plans to do beginning next year, is a step away from the cliff -- or, perhaps, a step toward scrambling back up it.

Why in the world should we be getting all this for free?

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/movies/20avatar.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/arts/music/20simon.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/19/arts/music/20orchestra.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/books/20garner.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/arts/design/20map.html?ref=arts

http://theater.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/theater/reviews/20safe.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/arts/design/20museum.html?ref=arts

http://movies.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/movies/20popstar.html?ref=arts

http://movies.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/movies/20room.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/books/20parker.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/arts/music/20mcgarrigle.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/books/20segal.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/arts/design/20sarkisyan.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/arts/music/20jellinek.html?ref=arts

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/world/asia/20china.html?ref=arts

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/arts-funding-takes-a-hit-under-proposed-ny-state-budget/

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/longevity-at-the-opera-the-domingo-phenomenon/

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/what-does-the-vatican-think-of-avatar-ask-the-critic-who-wrote-the-review/

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/grammys-plan-a-3-d-tribute-to-michael-jackson/

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/in-defense-of-pants-on-the-ground/

http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/better-late-than-never-a-welcome-gift-for-conan-obrien/

And that's just today's arts coverage -- so far.

The drama in Massachusetts at the moment is all about the Senate race, but it's an unhappy day for Boston popular fiction as well: Erich Segal, the creator of Oliver Barrett IV and Jennifer Cavilleri, and Robert B. Parker, the creator of Spenser, have both died.

I think of Jenny Cavilleri every time I drive past Cranston, R.I., on I-95, even though she never really lived there -- even though she never really lived. A little farther north, whole swaths of Boston and Cambridge are inhabited, if only in imagination, by Oliver and Jenny, Spenser and Susan.

In my 20s, when I was especially fond of detective novels and happened to be living in Massachusetts, I dipped into the Spenser books. As a teenager, I read and reread Segal's "Love Story." But, just as it was the TV series that introduced me to Spenser (Trinity Church, consequently, has faint echoes of the private eye for me), it was the movie "Love Story," also written by Segal, that led me to the novel.

One night in the '80s, I was babysitting for a family I barely knew when "Love Story" came on the TV. I'd already put the kids to bed, so I watched it, and by the end I was a sodden, tear-stained mess. Right after the credits rolled, the parents walked in the door. I remember the alarm in their faces as they looked at me, assuming some disaster had befallen their children. Still sniffling, I explained about Jenny's demise. The mom got it immediately.

About

Laura Collins-Hughes I've been an arts journalist since 1993. Until it folded as a print publication, I was deputy cultural editor of The New York Sun, where I wrote about the two areas of the arts closest to my heart: theater and books. more

Contact me Click here to send me an email... more