There is a recent piece at Lawfare, by Simon Goldstein and Peter N. Salib, “Copyright should not protect artists from artificial intelligence.” The article has the strawman subtitle, “The purpose of intellectual property law is to incentivize the production of new ideas, not to function as a welfare scheme for artists.”

I have a few problems with it, from their sloppy wording – they repeatedly say copyright is about protecting “ideas”, when it doesn’t; copyright law is pretty specific that it protects specific expressions, but not ideas in any grand sense – to what I think is a misguided understanding of the nature of the artist v AI dispute, to odd ideas about art in general, for example:

Like humans, AI companies need incentives to produce AI systems that will, in turn, produce novel poetry, visual art, music, and more. But the incentive here need not necessarily come from intellectual property. Poetry is non-rival in that, once written, a single poem may be enjoyed by everyone at no cost. But there is no law that says everyone must or even will wish to read the original poem.

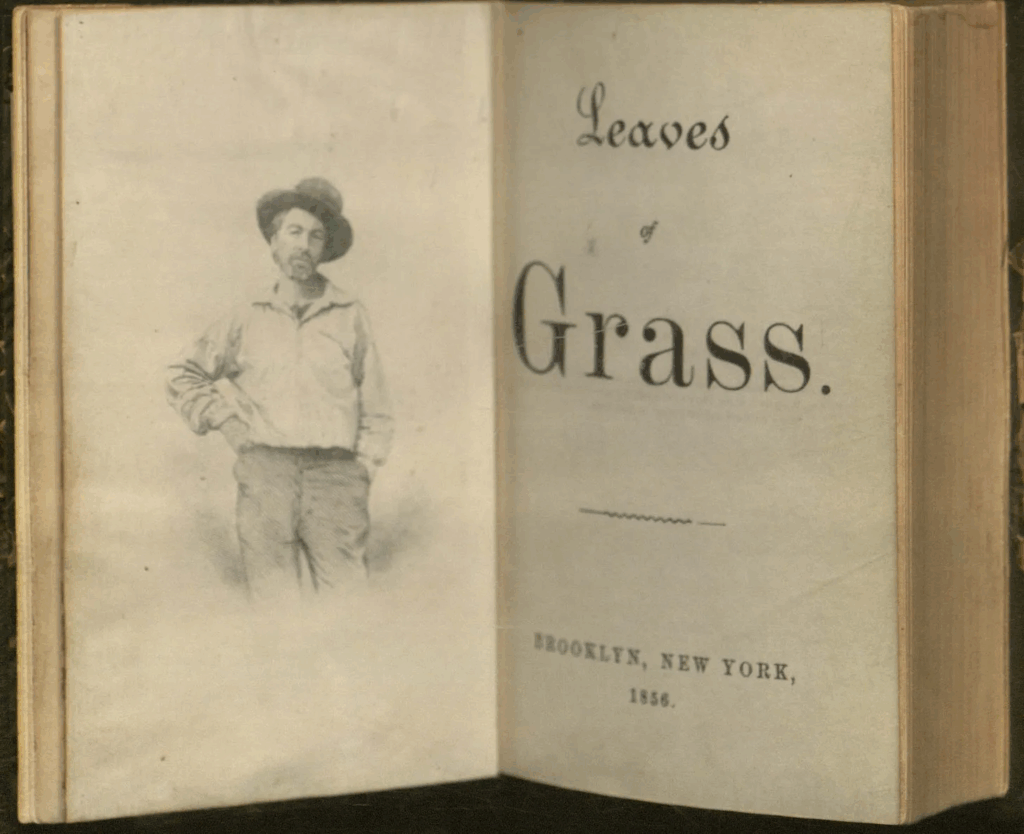

In a world where new works of great poetry are cheap and abundant, contract law can do the work that copyright does today. Rather than one Whitman laboring a lifetime over one “Leaves of Grass” in hopes of compensation via millions of readers, one Claude will write millions of works on par with “Leaves of Grass.” Each personalized for one or two readers. With the labor compensated—and then some—by a $20/month subscription fee.

I will just leave that there.

But let me get to where I think their main argument goes awry.

They point out correctly (notwithstanding their misuse of the word “ideas”) that copyright law is designed to strike a balance between incentivizing artists to produce new work, knowing copyright will give them the exclusive right to license publication, and access, for consumers (which is why it is good that works eventually enter the public domain), scholars, and the next generation of artists, who need room to be able to create new works without infringing on someone else’s copyright (if someone could copyright the “idea” of the chord sequence I IV I I IV IV I I V IV I I, we would have no more new blues songs). So far so good. The reason almost everybody thought the Copyright Term Extension Act (1998) was a terrible idea was that it further restricted access by delaying the entry of copyrighted works into the public domain for an additional twenty years, while having virtually no beneficial aspects in terms of incentives (my telling you that if you finally get around to writing that novel your copyright will last for seventy years after your death instead of just fifty is unlikely to have a prominent place in your decision to quit your day job and get writing).

But copyright does something else: it creates valuable assets that generate rents. If the extension of the term of copyright was such a terrible idea, why did Congress agree to it? Because there were certain firms (eg Disney) and authors’ estates who owned very valuable properties, ones that continue to generate streams of income decades after they were created, indeed decades after the artists who created them had returned to dust, and they did not want those properties going into the public domain. If I were a beneficiary of the portfolio of intellectual property created by Ernest Hemingway, I would like to continue to receive a stream of income from that asset for as long as possible. So even though copyright term extension did not make any sense in terms of the incentives / access trade-off, it really did make sense to a small group who lobbied hard for it (cf. the logic of collective action).

And it is this aspect of copyright, the battle for ownership of the income streams that can be earned from intellectual property, that the AI question is about.

There have been similar battles in the past when new technologies came into being. When cable television became a thing, and all these new channels could start showing reruns of old shows through syndication, those who worked on those programs wanted a share of this new revenue source, and fought for their rights to it. When the internets became a thing, and journals and newspapers started digitizing content for which they could sell access, the people who originally wrote those pieces wanted a share of the rents.

When Goldstein and Salib say that copyright is not designed to “function as a welfare scheme for artists”, well, sure. But it is not designed to be a welfare scheme for big tech firms either. The claim of artists, as I understand it, is that various producers of AI material are infringing copyright, making use of materials that goes beyond what have been the (sensible) provisions of fair use, and that if they are going to use material they ought to pay for it. Clearly, contracting between AI firms and millions of authors and songwriters would be impossibly complex, but a system of compulsory license might work (such as exists in music: I can record a cover version of Out on the Weekend without contracting with Mr. Young, but he will be entitled to a share of any royalties arising out of my tragic version).

They write:

Intellectual property rights always and everywhere create social loss. Ideas are non-rivalrous and, therefore, free for anyone to use. When intellectual property protects content creators from AI outputs, it makes it more difficult for anyone anywhere to access the incredible ideas that could be produced by AI outputs (or by humans). This kind of social loss requires strong justification. Historically, this justification has come from the incentive to produce new ideas. Without such a justification, it is unacceptable.

The alternative to intellectual property-as-welfare is actual welfare. Here, the best policy instrument is universal basic income, or something like it. Universal basic income avoids the problems of discrimination, distortion, and social loss. It could be given nonarbitrarily to all workers affected by AI automation. And it could be funded by general tax revenue. This means that the costs of universal basic income would not cause slowdowns on AI development, as compared with other technologies. Then the transition to cheap, abundant, AI-led innovation would allow everyone to costlessly access the immense value of innumerable non-rivalrous ideas.

The first sentence is simply wrong – we have patents and copyright because on the whole the system is socially beneficial. The rest of the first paragraph is wrong because the debate is not about preventing AI, but of finding a way to divide the returns from this new technology between the artists who created works and the AI companies that want to use those works. You can have a system that pays artists and still has AI – the authors present a false dilemma.

On the second paragraph, I just don’t know where to begin. Thanks for letting us use your book, here’s a welfare cheque.

The AI and artists question is a hard one, especially because the technology is moving so fast, faster than any legislative body could keep up with, much less the comically hopeless United States Congress. Predictions about what comes next are a mug’s game, and I don’t care about polls that show people can’t tell the difference between real Wordsworth and fake Wordsworth. But at least for now we can say what is at the heart of the battle, and it’s not what these authors claim it is.

Cross posted at https://michaelrushton.substack.com/

Leave a Reply