So, what’s the right question?

“See what the company looks like with a $6 million budget.”

“Okay, but you know the income will take a beating, too.”

“See what the company looks like with a $6 million budget.”

These were some of the final words spoken to me by a board member at the then-$12 million Alabama Shakespeare Festival. After a whole bunch of years of six-digit deficits, the company had finished in the black (by hook or by crook) during three of the four fiscal years in which I served as the managing director.

This board member, a kind but firm accounting sort, did not believe that the company was sustainable as it stood. He wasn’t wrong (and he wasn’t one of the racist board members, but a real person, so I wanted to help him), but this particular task was different and nearly impossible for one person to tackle, especially during those years.

And yet, he wanted me to take this on without telling my partner (or anyone else, for that matter): a $6 million budget to produce somewhere in the neighborhood of twelve plays for the upcoming fiscal year.

My problem was that I was too much of a people-pleaser at the time. It’s been a longstanding issue and has caused “analysis paralysis” in far more occasions that I care to admit.

Sometimes referred to as ‘choice paralysis,’ analysis paralysis causes you to have an intense, emotional reaction when faced with making a decision. While it’s not a medical diagnosis, it’s a symptom often tied to mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, and ADHD. But it can also happen even if you’re not dealing with a mental health issue.

“In some cases, analysis paralysis can lead to mental health difficulties, so it’s a little bit of a cycle in that way,” said psychotherapist Natacha Duke, MA, RP.

— Cleveland Clinic

I knew what the task was and I knew the reasons for it. The company’s activities were, in fact, unsustainable. But to halve the budget in one fell swoop — well, that was a task for someone who didn’t really care about the outcome. And that wasn’t me.

It was probably good, then, then shortly thereafter, my contract was not renewed and I just about sprinted back to Seattle. But that story has a lot of twists and turns that might make you puke all over the screen.

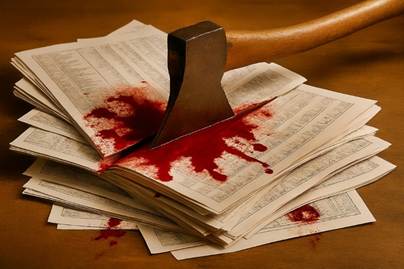

Cutting haphazardly is not the answer to any question about sustainability. Not one. And if that’s how your company is planning to “survive” this particular moment in history, yours will be just one more casualty along the battlefront, right next to those who appease by doing the people-pleasing thing (happy, popular events only), those who are experiencing analysis paralysis (let’s pretend nothing is wrong), and those who insist that artistic excellence is the ticket to sustainability (it’s not, because it’s a totally subjective metric — and, of course, it’s never worked before).

SMU DataArts (another in a long line of entities that, adorably, puts two words together with an upper-case letter in the middle of it all) noted that even when NOT adjusting for inflation, arts organizations were in full cutting unrestraint. “As organizations respond to declining revenue and higher prices, expense budgets tightened by an average of 23%. This decrease includes significant dips in both personnel and non-personnel expenses for the first time since 2021.”

Interestingly, funding for artists dropped only by 11% in the same time period.

Does that mean that administrative staffs are being cut? The quick answer is yes. “As a result of cuts in personnel expenses, part-time and full-time employees both decreased by two positions. After several years of stable or growing staff counts, this is the lowest they have been in the last six years, leaving many organizations with fewer staff to carry out operations.”

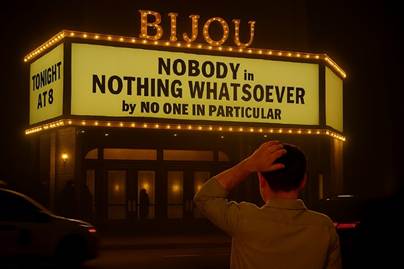

Sadly, there is no data showing whether these understaffed organizations (or were they overstaffed before now?) are effecting any positive impact on the communities they promised to serve when they registered for 501(C)(3) status. In fact, the only community members they counted were attendees, which are still far fewer than they were in pre-pandemic days. These numbers may never return in any robust way any time soon (except for that new production of Wonderful Town, starring Taylor Swift and P!NK).

The fear is this: what if cuts don’t work? What if audiences still don’t come back and, as a result, revenues still lag? The only thing left to cut is (more than 11% of) the artists themselves, and that seems like a bad idea, don’t you think?

Okay, maybe that’s too far-fetched. Of course the artists will be paid, right?

Right?

Instead of just cutting and cutting as though the year were still 1998 and you’ve still got a George Clooney hatchet man (from the movie Up in the Air) working for you, why not just redirect the organization to be a community-facing entity? This is a not-so-tangential reference to Jim Collins’ Good to Great metaphor of not only getting the right people on the bus, but putting them in the right seats. As an organization dependent on ticket sales, your company will always be at the mercy of popularity and other for-profit (and therefore irrelevant) metrics. Those are square pegs for the round holes of your success as a charitable organization.

Now is not the time to cut by some arbitrary figure or percentage. Now is the time to refocus what in the hell you’re doing as a nonprofit arts organization. Stop asking your people what the best version of your arts organization would resemble; ask what the best of your community would resemble. After that, just direct all your energies toward that. It is the most fundable kind of work any charity can do, speaking in mercenary terms. It’s also the right thing to do. And as I always seems to be saying, “Doing the right thing is always the right thing to do, no matter what.”

Great article! Experienced the reverse in 2020 (the dread COVID year). Fought to keep our 15 member ensemble of artist/administrators together – as a result, stayed healthy, bounced back quicker than others, and are still functioning!