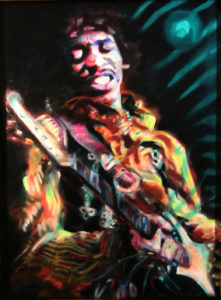

On the 80th anniversary of Jimi Hendrix’s birth (11/27/42), memory and legacy of America’s unsurpassed guitar-artist (written 2011): I’m bouncing around in the back seat of a pal’s car with a couple other high school wannabes, cruising through our leafy-green, cushy but staid Chicago suburb, when the most amazing music comes roaring out of the […]

Howard Mandel's Urban Improvisation