I just got the bright idea of live/remote coverage of today’s music at the Newport Jazz Fest – tweeting briefly but fleshing out comments here and on Facebook — wherever people respond. Follow me @jazzbeyondjazz or #newportjazz and hear the broadcast: http://t.co/acrBBnq I’ll start at 2:45 pm – with Regina Carter’s Reverse Thread performance — […]

Radio Days: Newport Jazz fest on NPR

National Public Radio does jazz fans worldwide a huge service today (Sat., Aug 6) and tomorrow, broadcasting live from the Newport Jazz Fest. See the complete schedule and listen at NPR.org if your local station’s not carrying the feed. I’ll be tuned in from 2:45 pm EDT for violinist Regina Carter’s African-referent Reverse Thread and […]

How Madeleine Peyroux is not Charlie Parker

What does folkie chanteuse Madeleine Peyroux have to do with Charlie Parker, the alto saxophonist who has defined the past 60 years of vernacular instrumental improvisation, namesake of a two-day fest that’s NYC’s final free summer fling? Everything (not quite) is revealed in my new CityArts column . . . howardmandel.com Subscribe by Email or […]

Saint Agnes Varis gave $ to jazz, opera & Democrats, dies age 81

Agnes Varis, a major progressive philanthropist funding the Jazz Foundation of America, Jazz at Lincoln Center and the Metropolitan Opera while fighting for reduced health care costs through perscription of generic drugs and supporting a broad array of Democratic and women’s issues, died of cancer July 29 at age 81. She was officially honored as “Saint […]

Remember the Swing Era: Is poverty good for jazz?

Jazz the music will survive the wounds America has self-inflicted in the guise of deep cuts in government spending when economic growth has already slowed to a crawl. Jazz — as well as blues, rap, hip-hop, soul, bluegrass, chamber music and most rock ‘n’ roll — is fairly cheap to produce, given workers (musicians) who […]

UNESCO names pianist Herbie Hancock “goodwill ambassador”

Pianist Herbie Hancock has been appointed a “goodwill ambassador” by UNESCO. The 71-year-old multiple Grammy winner, Chicago-born child prodigy, Miles Davis’ keyboards man ushering open-form improvisation, electronic instruments and studio procedures into the past half-century of jazz-based music and talent scout with global interests joins an international coterie that currently includes Nelson Mandela, Pierre Cardin, […]

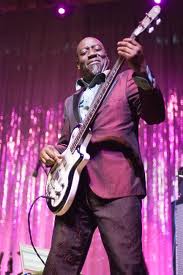

Free funk electric bassist gets $60k Pew Fellowship

Jamaaladeen Tacuma, free-funk electric bass virtuoso, protege of Ornette Coleman and one of the dancingest musicians on the planet, has been named one of 12 Philadelphia artists receiving $60,000 fellowships from the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. Two other musicians are also 2011 Pew fellows: electronic music improviser Charles Cohen and exploratory folk/rock/goth guitarist Chris […]

Beyond music in the waters off the City

Take a night-time jazz cruise with saxophonist Avram Fefer, guitarist Joe Cohn and rhythm in New York Harbor on Wednesday nights for respite from NYC – I detail it and other unusual musical staycations for July in my new City Arts New York column. If you’ve got 10 minutes, check out my dark video of […]

House Appropriations Committee to NEA: Keep Jazz Masters

The National Endowment for the Arts has been directed by the US House Appropriations Committee in its report to Interior  to continue the American Jazz Masters Fellowships and dump its proposed American Artists of the Year honors. The report also supports continuation of the NEA’s National Heritage Fellowships program (but not its Opera Honors) and recommends a 2012 NEA budget […]

Urban Realism and Treme

“Life is glorious and vibrant and joyous at points, but it is essentially tragic. That’s not a unique David Simon perspective.” So sayeth David Simon, (pictured left; right is a Mardi Gras Indian portrayed by Clarke Peters), executive producer with Eric Overmyer of Treme, in a long interview on Salon conducted by Matt Zolar Seitz.  The HBO series about […]

Hurray for Treme

“Do Watcha Wanna,” the season finale of Treme, had everything I watch the series for: Compelling characters embodied by terrific actors; plausible and suspenseful quick-cutting across and interweaving of plot strands; confident command of realities afflicting post-Katrina/pre-Gulf oil spill New Orleans, and the extraordinary depiction of living, breathing, hugely enjoyable music as a central factor […]

Symphonic “jazz” compositions, big bands and holiday blasts

The American Composers Orchestra readings of short symphonic works by jazz-oriented composers which I wrote of in my CityArts column and posted about here are now available to hear, thanks to Lara Pelligrinelli at NPR’s A Blog Supreme. The 23rd annual BMI/New York Jazz Orchestra concert, featuring “New Works for Big Band” and the naming (not […]

Jazz in Jordan: Yacoub Abu Ghosh explains and plays

Jazz and its evolution goes on everywhere – as bass guitarist/bandleader/composer/producer Yacoub Abu Ghosh explained and demonstrated to me in Amman, Jordan last March. Ghosh and his Stage Heroes performed at their weekly gig at Canvas Cafe Restaurant Art Lounge. His new album As Blue As The Rivers of Amman is due to drop July […]