Harris Eisenstadt, the subtle and substantive drummer/percussionist/composer, celebrates two decades of investigations and his recent projects at The Stone in NYC Sept. 1 through 6 with a circle of collaborators whose excellence seems to preclude their commerciality. That ain’t right, as Eisenstadt and the distinctly creative musicians in his ensembles (including Canada Day and Golden State, both […]

Jazz images Made in Chicago: PoKempner sees Steve Coleman, Greg Ward & Onye Ozuzu, Gary Bartz and more

Marc PoKempner may be best known for his photos of pre-presidential Barack Obama, Chicago’s reform mayor Harold Washington and the blues — but his jazz photography illuminates what we hear by refreshing how we see it. Here are some of his complex compositions in bracing color from the Pritzker Pavilion stage in Millennium Park, incorporating […]

China, Dave Koz learns, is hot for sax

Where will a new jazz audience arise? How about China? Not only have plans been announced to open a Blue Note Jazz Club in Beijing — since 2012, Hong Kong-based entrepreneur Jason Lee has helped pave the way by booking big name and somewhat lesser-known instrumentalists for tours reaching into “second tier cities” (populations between three and seven million) across the vast […]

Ten albums introducing Ornette Coleman’s musical evolution

An outpouring of media tributes has followed my hero Ornette Coleman’s death at age 85 on June 11. But many commentators writing of his music — including good ones like Marc Myers in Jazz Wax and Ben Ratliff of the New York Times — have focused mostly on Coleman’s breakthrough recordings from 1958 and ’59, overshadowing music from the last 45 years […]

Ornette Coleman returned music to freedom and basics

Sad news this morning: Ornette Coleman died at age 85. Triumphant news: Ornette Coleman returned music to its free-from-cant basics, emphasizing emotional communication and intuitive human interactions over any other elements in the dynamic, multi-faceted, immediate art form. I included several interviews with Ornette — whom I consider the most fascinating and broadly insightful man […]

Bob Belden’s most personal music: Black Dahlia

Bob Belden, the saxophonist-composer-arranger who died of a heart attack May 20 at age 58, was an enormously gifted, brave, original and productive musician. Last February he led his band Animation on a four-day performance tour of Iran, the first American to do so since 1979 — and videos he created with Bret “Jazz Video Guy” Primack, […]

Jazz Chicago this week — starting with NEA Jazz Master Joe Segal

Too much jazz in Chicago this week to write at length about it all, but also too much to ignore: Congrats to Joe Segal, proprietor of the Jazz Showcase forever, at various spots, inducted as an NEA Jazz Master. I owe Joe Segal big time, as he encouraged my 17-year-old interests in jazz and even let me […]

Bernard Stollman’s ESP disks: Medici of ’60s beyond jazz

Bernard Stollman, record producer of Albert Ayler, Paul Bley, Ornette Coleman, the Fugs, Sun Ra and many other iconoclastic musicians of the 1960s up to now on his ESP Disk ur-indie record label, died April 19 at age 85. I had the pleasure of interviewing Stollman — as well as Marzette Watts, Milford Graves and Frank […]

ESP Disks — origins of jazz beyond jazz

Reviewing a sleeping giant, ESP Disks before its early ’00s revival Howard Mandel c 1997, published in issue 157, The Wire It was a time before psychedelics. Following the seismic cultural disruptions of the mid ’50s, rock ‘n’ roll had hit a period of stasis, enlivened only by the occasional novelty number – the British […]

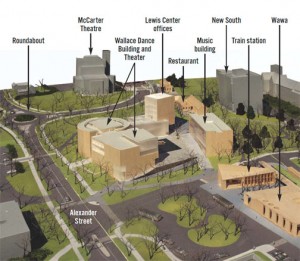

Big money for campus buildings for music

Last week big money was donated to construction of music buildings for two major U.S. universities. An anonymous Princeton alumni couple have pledged $10 million for a new music building at the New Jersey campus, and the University of Missouri has received $10 million, its largest gift ever for fine arts, from Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield for a […]

Ann Meier Baker, NEA director of Music and Opera, on her new job and NEA Jazz Masters

I’m pleased to have interviewed Ann Meier Baker, who was appointed last October as the National Endowment for the Arts’ director of Music and Opera – a position that includes responsibilities for the U.S.’s federal support of jazz, such as the induction of NEA Jazz Masters, celebrated with a live-streamed concert at Jazz at Lincoln […]

Guggenheim fellows include jazz-beyond-jazz creators

Four stellar jazz-beyond-jazz musicians — orchestra composer-leader Darcy James Argue, trumpeter Etienne Charles, saxophonist Steve Lehman and scholar-composer/improviser-electronics innovator-trombonist George E. Lewis, all practiced stretching the definition of “jazz”without breaking it — have been named 2015 fellows of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, among 175 “scholars, artists, and scientists [a]ppointed on the basis of prior achievement and […]

Doris Duke Performing Artists and JJA Jazz Heroes: Tale of two honor rolls

Six musicians identified with jazz have been named 2015 Doris Duke Performing Artists receiving $275,000 each, and 24 “Jazz Heroes” have been certified by the Jazz Journalists Association after nominations from local jazz communities across the U.S. Are comparisons between these two very different lists of honorees instructive? The Doris Duke Performing Artists are AACM co-founder-composer-pianist Muhal […]