The process to which the French word collage refers was invented by the Japanese more than 500 years ago. They tore strips out of old paintings, calligraphies and colored paper patches to reuse in new work.

Born in Japan, Seattle artist Paul Horiuchi (1906-1999) used collage much as his forebears did:

to set a meditative mood and to orchestrate color, form

and texture into a harmonious composition.

Horiuchi fused the sensibility of the Japanese rock garden with Western modernist expressive abstraction.

Horiuchi fused the sensibility of the Japanese rock garden with Western modernist expressive abstraction.

Seattle artREsource is host to a small but fine survey of his work, from the 1950s to the 1980s. Run by Jena Scott, artREsource is a gallery devoted to the secondary market. Rarely has she a chance to organize an exhibit, but once she had half-a-dozen first-rate Horiuchi’s, she sought more to make the show.

Horiuchi came to the States in his teens. He was working for the railroad in Rock Springs, Wyoming, when FDR signed Executive Order 9066. Because he, his wife and two young sons weren’t on the West Coast, they escaped detention. Instead, isolated from other Japanese-Americans and hearing rumors that they would be arrested or even killed, they burned a collection of old Japanese books and prints that had been in their family for generations.

Fired by the railroad for being of Japanese descent, he and his family lived in their car and later in a homemade house on a

truck, making a living through janitorial and gardening work.

The paintings and drawings he made during and before this period were stored in a friend’s basement and lost in a flood.

By the time he arrived in Seattle, he was a 40-year-old railroad man, auto mechanic, sign painter and artist. Mark Tobey was for him a catalyst, although when Horiuchi began making collages in 1956, Tobey told him to stick to watercolors, because his watercolors were so spare and beautiful.

In 1962, he created the 70-foot-long Mural Amphitheater for the World’s Fair in Seattle.

During his career, he was awarded prizes and purchase awards from the Ford Foundation, the Rome-New York Foundation and the Carnegie Art International. Japan designated him a sacred treasure.

The tumult of his life does not appear in his work. Instead, there’s a serene balance of color and weight with a strong, underlying vitality, a sense of dynamic forces being brought into line.

Through May 8. (Extended through May 29.)

Although he calls her a “true original,” he locates her among her peers, where her work falters. On the other hand, besides the artists mentioned below, he throws in

Although he calls her a “true original,” he locates her among her peers, where her work falters. On the other hand, besides the artists mentioned below, he throws in  To Crumb and Frey I’d add

To Crumb and Frey I’d add  And

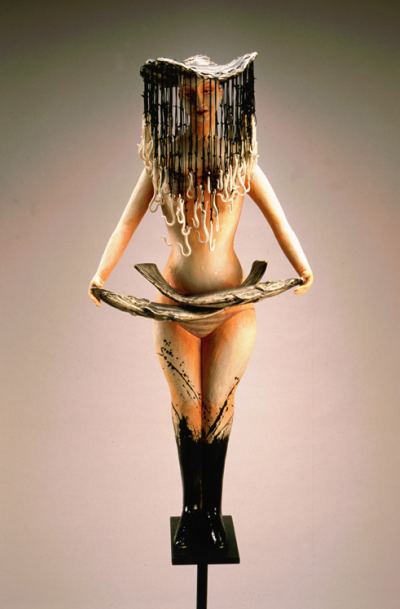

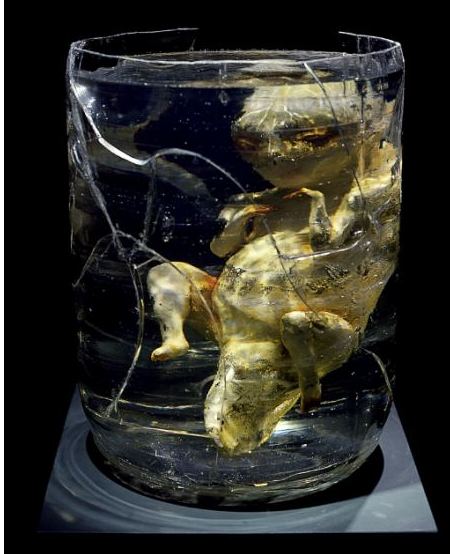

And  Grossman was just starting out in the 1970s, but she would not only shine in a Crumb-Frey-Warashina exhibit, she’d make the others shine too. She’d bring out both the mournful melody of the collective theme and the relish in its depiction.

Grossman was just starting out in the 1970s, but she would not only shine in a Crumb-Frey-Warashina exhibit, she’d make the others shine too. She’d bring out both the mournful melody of the collective theme and the relish in its depiction.  Silky as perfumed employees of the pleasure quarter:

Silky as perfumed employees of the pleasure quarter:  Why swarm?

Why swarm?

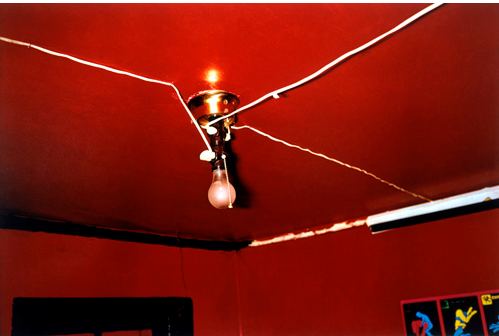

When Smith spoke Thursday night to a packed house, many who showed up probably thought she’d talk about the exhibit. She touched on it but turned away, saying only that she began using photographs of her work as work when she needed to fill a space and improvised the photos into a kind of serial narrative.

When Smith spoke Thursday night to a packed house, many who showed up probably thought she’d talk about the exhibit. She touched on it but turned away, saying only that she began using photographs of her work as work when she needed to fill a space and improvised the photos into a kind of serial narrative.

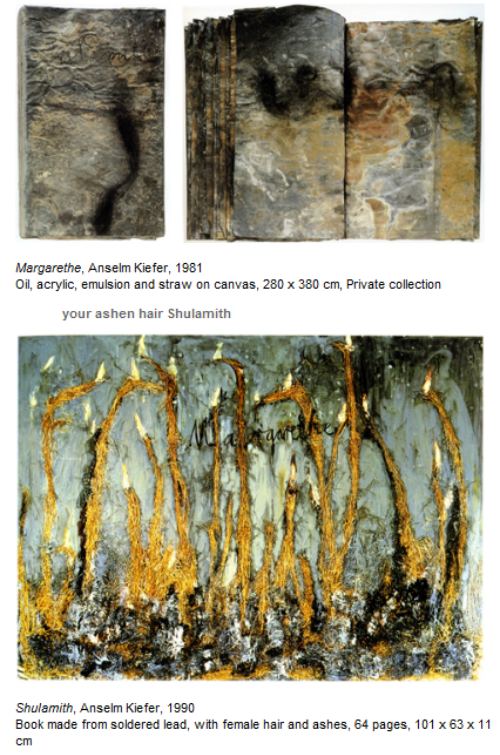

Gorky, How My Mother’s Embroidered Apron Unfolds in My Life Oil on Canvas 1944, Collection,

Gorky, How My Mother’s Embroidered Apron Unfolds in My Life Oil on Canvas 1944, Collection,  Part 2, the poems,

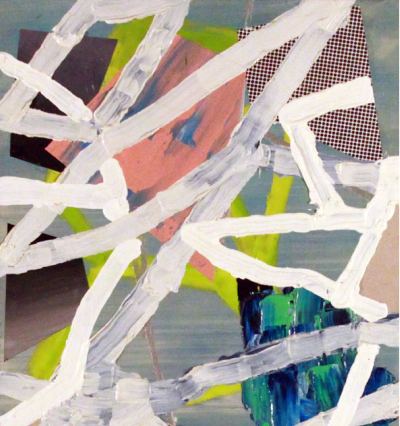

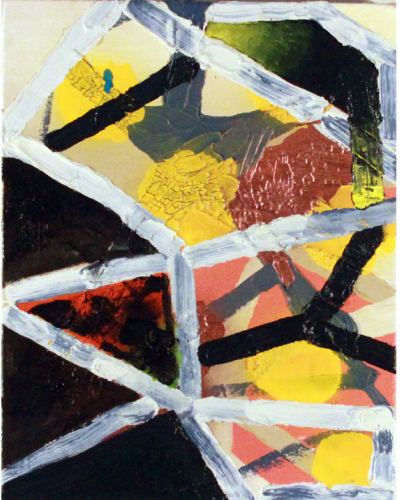

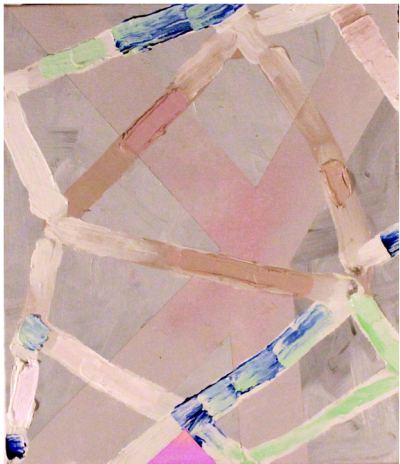

Part 2, the poems,  Kroll works small, usually in oil and enamel but occasionally with some element of collage. Ambitious paintings that span no more than two joined hands used to be unusual, back when

Kroll works small, usually in oil and enamel but occasionally with some element of collage. Ambitious paintings that span no more than two joined hands used to be unusual, back when  Some look at Kroll’s work and see nothing but sources: He owes everything to

Some look at Kroll’s work and see nothing but sources: He owes everything to  Through March 27.

Through March 27. From Anna Callahan :

From Anna Callahan :