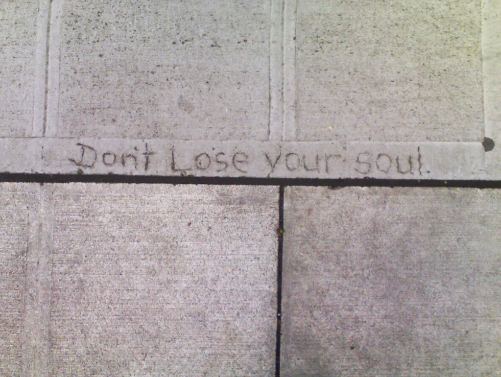

Laura Casatellanos Castellanos collects messages written in the pavement, before the cement hardens. The one below she found across the street from Seattle’s Millionair’s Club Charity in Belltown, on Western near Wall St.

Previous message here.

Previous message here.

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Laura Casatellanos Castellanos collects messages written in the pavement, before the cement hardens. The one below she found across the street from Seattle’s Millionair’s Club Charity in Belltown, on Western near Wall St.

Previous message here.

Previous message here.

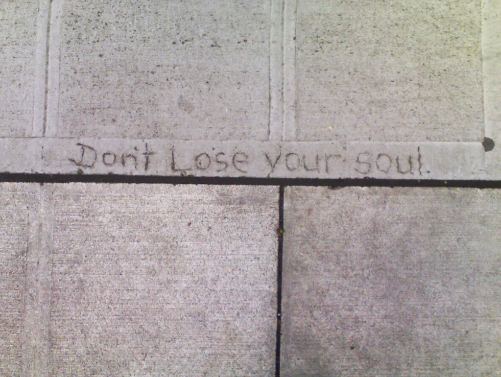

The content in painting is always the painting, the question being not who but how. That’s why it’s possible for a painter to tip his hat to Max Beckmann with a bird painting even though Beckmann concentrated on the human, not the avian.

Max Beckmann, Double Portrait

1946

Oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Image via)

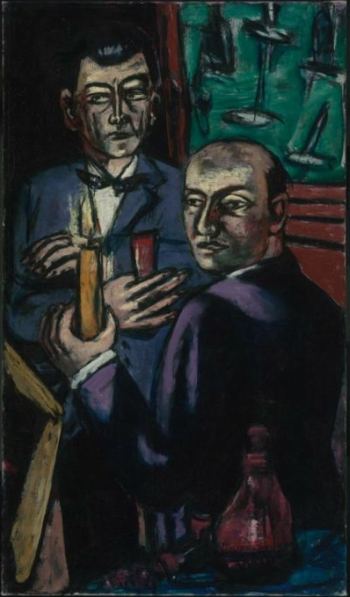

Beckmann, Still Life With Fallen Candles, oil/canvas 1929 Detroit Institute of the Arts (Image via)

Beckmann, Still Life With Fallen Candles, oil/canvas 1929 Detroit Institute of the Arts (Image via)

Brooklyn’s Andrew Keating picked up on Beckmann’s essential qualities and spun them into a feathered form whose fluid simplicity makes it contemporary. Keating’s bird is contemporary

Brooklyn’s Andrew Keating picked up on Beckmann’s essential qualities and spun them into a feathered form whose fluid simplicity makes it contemporary. Keating’s bird is contemporary

with an early 20th-Century heart. Beckmann’s rough paint handling is

there, his coarse intensity and bursts of bright

tonalities.

Keating Lucy, oil/linen, 2009 9 x 12 inches

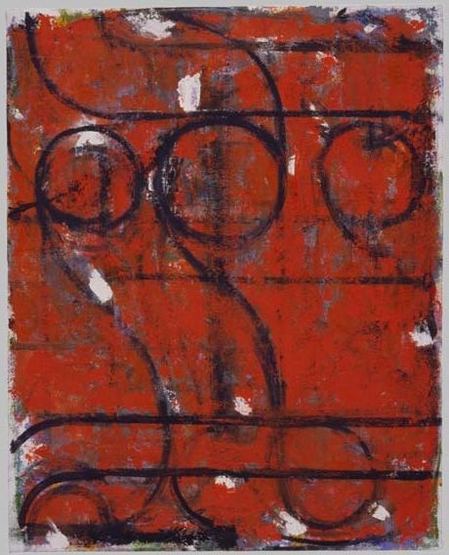

Beckmann wasn’t an abstract artist either. Seattle’s Robert

Beckmann wasn’t an abstract artist either. Seattle’s Robert

C. Jones takes a balcony lattice abstracted from Matisse and painted it as Beckmann might have, with black soiling his red silks.

Jones, Mexico Red, 2009 oil/canvas 20 x 16 inches

In painting, the new has roots in the old or it doesn’t matter.

In painting, the new has roots in the old or it doesn’t matter.

Why is it, despite their evocative shapes,

that clams and mussels rarely make an appearance in art? Is it because of Marcel Broodthaers? To use them again is to stand in his shadow.

(Image via)

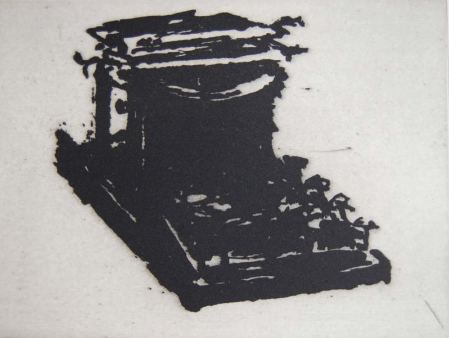

Andre Petterson, opening in June in Foster/White Gallery, is giving it a go from a different angle: Shells as evidence of geological layering bursting from the innards of an outdated machine. Except for the inexplicable addition of red, I’m with him.

Andre Petterson, opening in June in Foster/White Gallery, is giving it a go from a different angle: Shells as evidence of geological layering bursting from the innards of an outdated machine. Except for the inexplicable addition of red, I’m with him.

Of course, the outdated machine he chose has already unraveled as a kind of signature for William Kentridge.

Of course, the outdated machine he chose has already unraveled as a kind of signature for William Kentridge.

(Image via Greg Kucera Gallery)

You gotta know the territory. It’s also true that artists who let the past stop them make no mark on the present.

You gotta know the territory. It’s also true that artists who let the past stop them make no mark on the present.

Mutations make language stronger. A cheap toy becomes a treasure through its description.

What notebook has ever loved you more?

What notebook has ever loved you more?

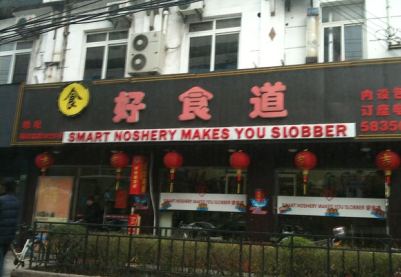

Both images from Engrish.com, via Christine Tokunaga. (First post, The Curse of the Monolingual, here.)

Both images from Engrish.com, via Christine Tokunaga. (First post, The Curse of the Monolingual, here.)

In 1991, Chris Burden wanted to hang a fishing boat off the side of the Seattle Art Museum, designed by Robert Venturi. Over my dead body, said Venturi. The architect is still alive. It didn’t happen.

Fifteen years later, the idea reappeared in the work of his wife, Nancy Rubins. He was thinking of something rough and working class – roots music for a city with a working waterfront. For another waterfront town, she delivered a flamboyant tiara.

Pleasure Point, 2006, nautical vessels, stainless steel, stainless steel wire. Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego Photo by Pablo Mason. (Via)

It’s ignorance, of course, especially for those who don’t understand a language that is printed on their shirt or tattooed on their body.

Case in point: Visiting a sister who lived in an apartment a short train ride from Tokyo, I joined her and her two small sons in a visit to a nearby park. Also in the park was an impeccably dressed young mother of my sister’s acquaintance. The legend sewn in pink lettering on her crisp white sweatshirt was an invitation to engage in oral sex disguised as a platitude: Kiss All My Lips.

I wanted to tell her. My sister, who prevailed, didn’t. She argued that woman wouldn’t wear a sweatshirt in the city. Tourists didn’t come to this suburb, so the chance she’d be laughed at was remote. Even if the woman encountered other English speakers in the park, they would be unlikely to say anything either. Confrontation causes face loss. What is not spoken of can be ignored.

My sister speaks four languages. She could afford to feel a touch superior, which she did and denied. Speaking only one, I identified with the woman’s plight. At the corners of our single-language consciousness are other worlds we cannot enter, because we lack the linguistic pass.

Some monolingual English speakers fail to demonstrate the humility their condition requires. They’re proud of what they don’t know. Isn’t simple jealousy part of the Arizona problem? Because they live in one world, they hate the sight (and sound) of those brave enough to attempt two.

The New York Times recently posted a series of photographs documenting the mangled English on commercial signs in Shanghai. As we laugh, we who do not understand Chinese should consider how well we’d do in Shanghai, relying on our English-Chinese dictionary to get the job done.

Image, New York Times

In response to this post, which notified the avid public that Seattle’s Charles

Krafft and Mike Leavitt

are showing at London’s Stolen Space

Gallery, Krafft sent the following comment:

We (Mike Leavitt and I) were taken to dinner the night before last by Jason Zeloof a partner in the Stolenspace Gallery which is on Brick Lane in The Old Truman Brewery in London’s trendy East End. Our fourth at the table was Robert Lands of Finers Steven & Innocent LLP who is the personal solicitor of the mysterious and beloved Banksy. Afterwards we repaired to the rooftop bar of the Shordich House, a private club in the neighborhood where I ordered a “Gay Butler” – soda and bitters on the rocks. There were lots of attractive women there. They were attractive because their blouses were lightly starched and their downy little arms curiously devoid of tattoos.

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise

Auden

Consider the case of Bruce Nauman. Along with David Hammons, Nauman is point person for the late 20th Century, early 21st Century divide. He’s the Samuel Beckett of the visual realm, documenting his body in space, from its most routine motions to its grunts and sighs, its failed dime-store dreams and dashed desires. Because his work has been absorbed into the body of contemporary art, it

mutates every day into other people’s uses of it.

In his studio on his ranch in New Mexico, however, the world that considers him a currency is far away. His ratty table before him, he sits on one of those expensive chairs favored by those with bad backs, his one concession to his status. Maybe he hears a horse whinny or a dog bark. He’s alone but not as alone as he imagined. Flipping through a manuscript, he finds mice turds and nibbled pages.

Enter rodents, stage left.

Office Edit 11, a video loop from 2001, presents what a surveillance camera discovered when left on in his studio overnight, sped up for the video. Furry interlopers the size of a toddler’s fist streak through space, stop dead and streak again, like paint brushes trailing invisible ink. Just as the human body is an instrument of its consciousness, Nauman’s mice play themselves like violins.

His studio becomes a stage, and all the mice are actors on it. It’s a tale told by a mechanical idiot, otherwise known as a camera. The image shifts in tone, from porous and flat to an old-world shine. At one point, tired of verisimilitude, the image stands on its head.

Office Edit II is in Box with the Sound of Its Own Making at Western Bridge. The title comes from Robert Morris, whose 1961 sculpture of that title is owned by the Seattle Art Museum. The title is Morris’, but the artists in it (who are not Nauman) have hitched their wagons to his star.

The brothers Elias Hansen and Oscar Tuazon are in the parking lot with Use It For What It’s Used For, a piece that first appeared in New York in 2009 thanks to the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. With poured concrete floor, skewered metal beams and solar-powered lights, it’s best seen at night. Like Nauman pacing off the steps he takes to walk circles in his studio, Use It For What It’s Used For goes nowhere. Completing it would be a stain on its silence.

(Image via)

Jonathan Monk‘s Nauman tribute is direct, transforming Nauman’s deadpan absurdity into visual vaudeville. Monk’s white neon sculpture from 2007 is titled, The Space Between My Index Finger and My Middle Finger Enlarged to the Size of the Space Between My Legs, riffing on Nauman’s A Cast of the Space under My Chair, from1965-68. (Nauman made that piece and moved on. Decades later, Rachel Whiteread picked up the theme and made a career of it. She is her own Nauman cover band.)

Jonathan Monk‘s Nauman tribute is direct, transforming Nauman’s deadpan absurdity into visual vaudeville. Monk’s white neon sculpture from 2007 is titled, The Space Between My Index Finger and My Middle Finger Enlarged to the Size of the Space Between My Legs, riffing on Nauman’s A Cast of the Space under My Chair, from1965-68. (Nauman made that piece and moved on. Decades later, Rachel Whiteread picked up the theme and made a career of it. She is her own Nauman cover band.)

Three or four years ago, when Western Bridge exhibited Jason Dodge’s Into Black from 2006, I thought the project came perilously close to nothing at all. Today the economy of its means strikes me as oddly moving. It consists of undeveloped photo paper exposed for the first time at sunrise on the vernal equinox 2006 in eight different places in the world. The sheets are blanks aspiring to color, darks groping toward light.

Maybe it’s the company Into Black is currently keeping, not just the other artists in the show, but other work by Dodge, including your death (copper pipe) and a current (electric). Both are a lovely kind of pared down poetry.

That leaves Ryan Gander and his process wallpaper. (Image of detail from Felix provides a stage, from A sheet of paper on which I was about to draw, as it slipped from my table and fell to the floor, from 2008.

He failed to achieve a likeness, but his documentation of that failure is robust.

He failed to achieve a likeness, but his documentation of that failure is robust.

Through July 31. Open Thursdays-Saturdays, noon-6 p.m. Free admission.

Among the Seattle exhibits I missed writing about last month, when I was first in New York and later part of ArtsJournal’s malware attack that shut the site down, is Adam Satushek’s Annex at Platform Gallery.

His photos have a whistle-while-we-work nuttiness. With the lightest of touches, Satushek documents the exuberant irrationality of never-say-die. Missing is any sense of disdain, as if the photographer also believes that mice can be men, and a Mr. Fixit approach to decor can turn a tracked home into a forest.

The sun hangs like a phlegm in the dirty handkerchief of the sky in Oscar Tuazon’s recent installation at Maccarone: post-apocalyptic desolation in a fine-boned body, corrosive content merged with grace.

(Tuazon images via)

Meanwhile, in Seattle, his brother Elias Hansen talked about his exhibit at Lawrimore Project last Saturday, the show’s last day.

Meanwhile, in Seattle, his brother Elias Hansen talked about his exhibit at Lawrimore Project last Saturday, the show’s last day.

Here’s Eli’s sun:

It’s a lens, the kind used to spark a fire in the woods, or maybe the bottom of a Coke bottle. Tuazon and Hansen see darkly, like fogs condensed, but there are differences. The former has the feel of a massive utterance, and the latter mutters into his hands, his useful, practical hands.

It’s a lens, the kind used to spark a fire in the woods, or maybe the bottom of a Coke bottle. Tuazon and Hansen see darkly, like fogs condensed, but there are differences. The former has the feel of a massive utterance, and the latter mutters into his hands, his useful, practical hands.

Another difference: Aside from collaborating with his brother, Tuazon appears to be a bit of a solitary. Hansen almost always works with others and makes art about being with others, specifically, what they did in their youths, looking for shots of sainthood through drugs and kids’ salvage saved in cigar boxes under the bed.

Hansen is also a glass blower, which is inherently a collaborative medium. As Jen Graves noted, there’s more than a touch of Dale Chihuly‘s Venetians in piece below, especially the concrete urn at the lower right:

Hansen is also a glass blower, which is inherently a collaborative medium. As Jen Graves noted, there’s more than a touch of Dale Chihuly‘s Venetians in piece below, especially the concrete urn at the lower right:

Like Mark Zirpel, Hansen is a new future for Northwest glass. Stripped bare of an interest in the decorative, their brides no longer look to Versailles or Murano. They use the trains of their dresses to make tents, and the cakes they eat come from ovens they build themselves. (Previous post here.)

Like Mark Zirpel, Hansen is a new future for Northwest glass. Stripped bare of an interest in the decorative, their brides no longer look to Versailles or Murano. They use the trains of their dresses to make tents, and the cakes they eat come from ovens they build themselves. (Previous post here.)

an ArtsJournal blog