It’s ignorance, of course, especially for those who don’t understand a language that is printed on their shirt or tattooed on their body.

Case in point: Visiting a sister who lived in an apartment a short train ride from Tokyo, I joined her and her two small sons in a visit to a nearby park. Also in the park was an impeccably dressed young mother of my sister’s acquaintance. The legend sewn in pink lettering on her crisp white sweatshirt was an invitation to engage in oral sex disguised as a platitude: Kiss All My Lips.

I wanted to tell her. My sister, who prevailed, didn’t. She argued that woman wouldn’t wear a sweatshirt in the city. Tourists didn’t come to this suburb, so the chance she’d be laughed at was remote. Even if the woman encountered other English speakers in the park, they would be unlikely to say anything either. Confrontation causes face loss. What is not spoken of can be ignored.

My sister speaks four languages. She could afford to feel a touch superior, which she did and denied. Speaking only one, I identified with the woman’s plight. At the corners of our single-language consciousness are other worlds we cannot enter, because we lack the linguistic pass.

Some monolingual English speakers fail to demonstrate the humility their condition requires. They’re proud of what they don’t know. Isn’t simple jealousy part of the Arizona problem? Because they live in one world, they hate the sight (and sound) of those brave enough to attempt two.

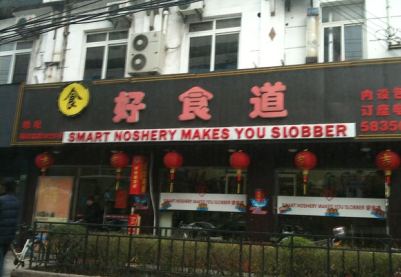

The New York Times recently posted a series of photographs documenting the mangled English on commercial signs in Shanghai. As we laugh, we who do not understand Chinese should consider how well we’d do in Shanghai, relying on our English-Chinese dictionary to get the job done.

Image, New York Times

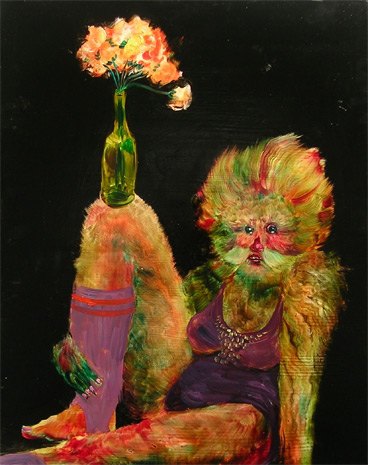

He failed to achieve a likeness, but his documentation of that failure is robust.

He failed to achieve a likeness, but his documentation of that failure is robust.

Meanwhile, in Seattle, his brother Elias Hansen talked about his exhibit at

Meanwhile, in Seattle, his brother Elias Hansen talked about his exhibit at  It’s a lens, the kind used to spark a fire in the woods, or maybe the bottom of a Coke bottle. Tuazon and Hansen see darkly, like fogs condensed, but there are differences. The former has the feel of a massive utterance, and the latter mutters into his hands, his useful, practical hands.

It’s a lens, the kind used to spark a fire in the woods, or maybe the bottom of a Coke bottle. Tuazon and Hansen see darkly, like fogs condensed, but there are differences. The former has the feel of a massive utterance, and the latter mutters into his hands, his useful, practical hands. Hansen is also a glass blower, which is inherently a collaborative medium. As Jen Graves

Hansen is also a glass blower, which is inherently a collaborative medium. As Jen Graves  Like

Like

Finally, Rina Castelnuovo at

Finally, Rina Castelnuovo at

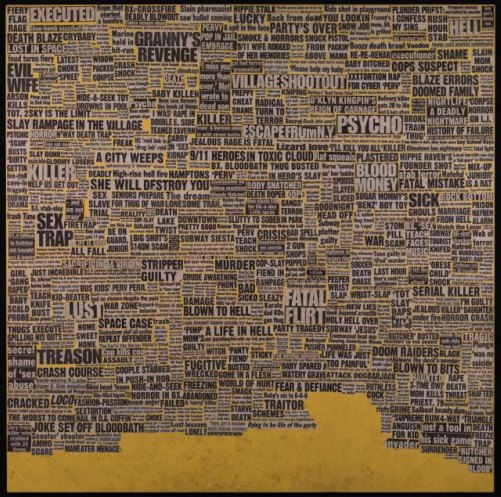

Still the best word on art & DNA is Robin Held’s 2002 exhibit, Gene(sis): Contemporary Art Explores Human Genomics at the

Still the best word on art & DNA is Robin Held’s 2002 exhibit, Gene(sis): Contemporary Art Explores Human Genomics at the