Now that journalism has succeeded in removing the journalists, losses are slowing and newspapers are at long last carrying on. Staffs are smaller, but the work goes on, not, of course, at the newspapers that folded early, such as my own, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, RIP March 17, 2009.

With 10 (or is it 8?) journalists replacing a staff of around 200, the PI continues online as a delusion of itself. This shallow but sprightly mirage continues to attract traffic. In doing so, it’s shaping up to be a financial success and a journalistic disaster. Why should publishers continue to pay (and put up with) writers, photographers, editors, artists and support staff who expect real salaries and health insurance, not to mention vacations and sick leave? Now there’s an alternative: a bare bones group with a bare bones compensation. What they can’t cover in their overheated work day can be covered by freelancers. The new meaning of freelance means you work for free.

The anniversary of the PI’s demise drew comment from former staffers. One thing you can say about journalists. They continue to type, even after their platform is gone.

One of my favorite PI reporters, Andrea James, now works in finance. From her new dollars and cents perspective, she finds her old paper lamentable. Her blog post, A well-run business it wasn’t, argued just that. What she left out is everything that mattered. In spite of shrinking resources, the PI that folded was the best version of itself in my more than two decades of employ there. The infusion of tough-minded young staff inspired those who’d been jogging in place to walk back into the world of who/what/when/where/why. The PI had the best chief editor I’d ever worked for, David McCumber, and a sane publisher, Roger Oglesby. (Sane publishers were not a given at the old PI.)

The wrong paper folded, leaving the fat-cat Seattle Times. Fine reporters work there, but the culture is one of Panglossian self-congratulation. Unless you piss Kool-Aid into the cup, you won’t be hired. To secure a slot you have to be blind to the egregious faults of the right-wing bully in charge, Frank down-with-death-taxes Blethen.

Nobody had to swear allegiance at the PI; in fact, skepticism was prized. A good newspaper is not a religion. Leaps of faith are discouraged. Instead, there is the daily hunt for big-game facts, for stories that are as accurate and fair-minded as the humans producing them are capable.

Where are we now?

What I think of as the PI Brain Trust is operating online as Investigate West, run by the great Rita Hibbard. The Seattle Post-Globe has turned into a good local news source. Plenty of former staffers have blogs, and the Post-Globe links to them, including my own.

A recent addition to the former PI staff blog roll is D. Parvaz’s well-named Something to Say. Fresh from a Neiman, she’s an Iranian-born Maureen Dowd: an enemy of cliche and advocate for clear thinking. I hadn’t realized how much I missed her voice until I started reading it again. Referring to new research on suicide bombers, she wrote:

A recent addition to the former PI staff blog roll is D. Parvaz’s well-named Something to Say. Fresh from a Neiman, she’s an Iranian-born Maureen Dowd: an enemy of cliche and advocate for clear thinking. I hadn’t realized how much I missed her voice until I started reading it again. Referring to new research on suicide bombers, she wrote:

As it turns out, strapping a bomb to oneself and killing others in

the process of detonating it isn’t anyone’s first choice.

Thought that Allah and the 49 promised virgins covered the topic? Reading Parvaz will take your mind to the gym. Her blog is my one-year anniversary present to myself, evidence that my peeps are everywhere, doing good work.

Most of his friends remember him not for his tragedy, which included mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction, but for his talent, his generosity, his steadfast loyalty and gleeful charm when the debilitating fog of illness lifted.

Most of his friends remember him not for his tragedy, which included mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction, but for his talent, his generosity, his steadfast loyalty and gleeful charm when the debilitating fog of illness lifted. How brilliant it would have been to pair it with a

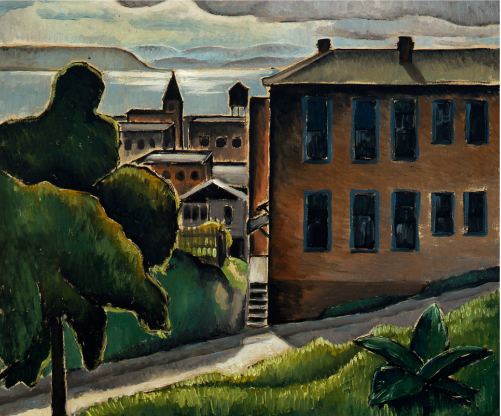

How brilliant it would have been to pair it with a  With light rimming his forms, Nomura conveys a quiet kind of Surrealism that predates Wayne Tiebaud’s. With painter

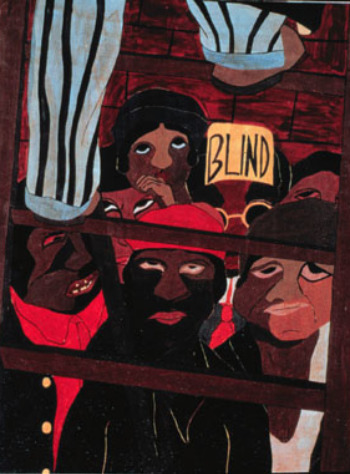

With light rimming his forms, Nomura conveys a quiet kind of Surrealism that predates Wayne Tiebaud’s. With painter  When you’ve got it, flaunt it. The Seattle Art Museum does not own a Lawrence as good as this one.

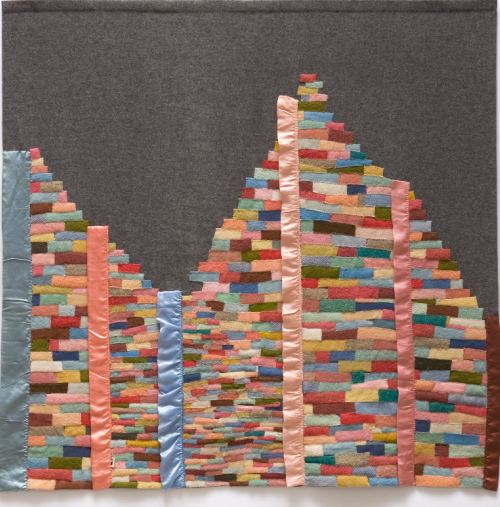

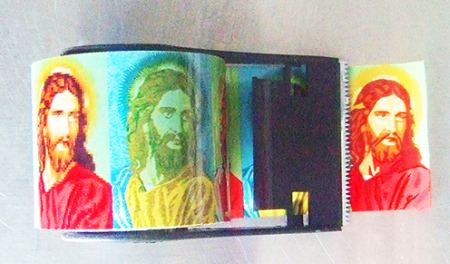

When you’ve got it, flaunt it. The Seattle Art Museum does not own a Lawrence as good as this one.  I love Seubert’s series, 10 Most Popular

I love Seubert’s series, 10 Most Popular In this telling of the Northwest tale, painters rule, not only in the past but in the present. That dominance represents a selective fiction. All we can ask of fiction is that it be convincing, and this one is, at least for the duration of the show.

In this telling of the Northwest tale, painters rule, not only in the past but in the present. That dominance represents a selective fiction. All we can ask of fiction is that it be convincing, and this one is, at least for the duration of the show. Through May 23.

Through May 23.

Wheeler’s inkjet prints are part of

Wheeler’s inkjet prints are part of  As Ben told his younger brother

As Ben told his younger brother  Detail:

Detail: The only other artist who makes such an exuberant overuse of tiny nails is

The only other artist who makes such an exuberant overuse of tiny nails is

He remembers elementary school, feeling pinned in place.

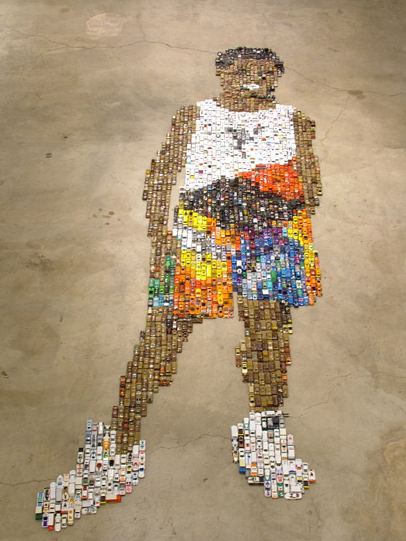

He remembers elementary school, feeling pinned in place. Inside his childhood was a loose and lovely obsessive. Hence his self-portrait (at age 9) in 1,649 hot wheels, each loose on the floor and capable of wheeling away. Some he painted, largely brown, as there aren’t a sufficient store of brown hot wheels on the market.

Inside his childhood was a loose and lovely obsessive. Hence his self-portrait (at age 9) in 1,649 hot wheels, each loose on the floor and capable of wheeling away. Some he painted, largely brown, as there aren’t a sufficient store of brown hot wheels on the market. Detail:

Detail: At

At

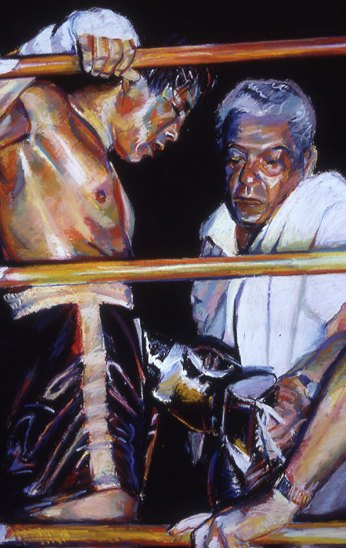

David Hammons’ 1989 Champ is impeccable and clever, beautiful and sad. The materials are simple: inner tube, (silver) duct tape, and boxing gloves (with laces hanging down). Hammons smartly mixes a deflated sport with deflated materials to examine the role of the prize fighter in American culture, especially black culture. Before the NBA was a dreamed-of escape-valve for urban youth, boxing offered the bruising, difficult way up. Fighters such as Jack Johnson and Joe Louis were heroes to black America, fighters who crossed-over and had success in mainstream society. But with success came tragedy: Louis died broke, his funeral paid for by German rival Max Schmeling. The tragedy went beyond individual figures: Countless young black men hoped boxing would provide a way up but instead were merely pummeled, used as entertainment or in match-fixing schemes, as disposable cogs in brutal entertainment.

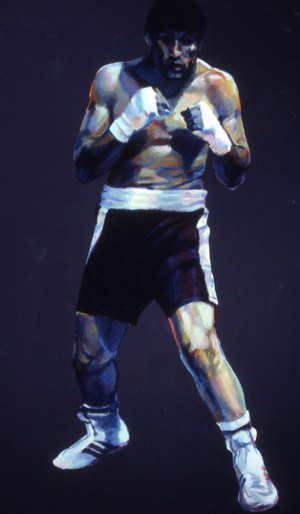

David Hammons’ 1989 Champ is impeccable and clever, beautiful and sad. The materials are simple: inner tube, (silver) duct tape, and boxing gloves (with laces hanging down). Hammons smartly mixes a deflated sport with deflated materials to examine the role of the prize fighter in American culture, especially black culture. Before the NBA was a dreamed-of escape-valve for urban youth, boxing offered the bruising, difficult way up. Fighters such as Jack Johnson and Joe Louis were heroes to black America, fighters who crossed-over and had success in mainstream society. But with success came tragedy: Louis died broke, his funeral paid for by German rival Max Schmeling. The tragedy went beyond individual figures: Countless young black men hoped boxing would provide a way up but instead were merely pummeled, used as entertainment or in match-fixing schemes, as disposable cogs in brutal entertainment. Hayes began his career in early 1980s, painting figures who deliberately draw the hard light of public scrutiny: strippers, boxers and prostitutes. Light splatters their bodies like oil hitting a hot griddle.

Hayes began his career in early 1980s, painting figures who deliberately draw the hard light of public scrutiny: strippers, boxers and prostitutes. Light splatters their bodies like oil hitting a hot griddle.

As John Yau pointed out in his monograph on Hayes from 2000, titled,

As John Yau pointed out in his monograph on Hayes from 2000, titled,