Albert Schweitzer practices Bach on the pedal piano at his hospital in Africa:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Almanac: Anthony Powell on the committed man

“His reactions placed him more and more as a recognisable type, spending much of his time in boredom and loneliness, yet in some way inhibited from taking in anything relevant about other people: at home only with ’causes.'”

Anthony Powell, At Lady Molly’s

TT: Snapshot

Albert Schweitzer practices Bach on the pedal piano at his hospital in Africa:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“His reactions placed him more and more as a recognisable type, spending much of his time in boredom and loneliness, yet in some way inhibited from taking in anything relevant about other people: at home only with ’causes.'”

Anthony Powell, At Lady Molly’s

Oasis

I’m flying back to New York on Thursday after a month and a half in Florida. I haven’t been on vacation–nothing like it–but my stay wasn’t exactly frenzied, either. Everything will change, however, as soon as I get off the plane. Not only must I grapple simultaneously with a snowstorm, a string of press previews and deadlines, and the inescapable turmoil of the fast-approaching opening night of Satchmo at the Waldorf, whose first public preview performance takes place on Saturday, but I’ll also be looking after three houseguests this weekend. My life, in other words, will soon be turned upside down and shaken vigorously, and I’m already feeling the weight of what’s to come.

In order to calm myself, I went this afternoon to Matisse as Printmaker, a touring exhibition of sixty-three aquatints, color prints, etchings, linocuts, lithographs, and monotypes that is up at Rollins College’s Cornell Fine Arts Museum through March 16. I was exceedingly frazzled when I walked into the museum, but within a minute or two I had already started to decompress, and an hour later I was myself again.

In order to calm myself, I went this afternoon to Matisse as Printmaker, a touring exhibition of sixty-three aquatints, color prints, etchings, linocuts, lithographs, and monotypes that is up at Rollins College’s Cornell Fine Arts Museum through March 16. I was exceedingly frazzled when I walked into the museum, but within a minute or two I had already started to decompress, and an hour later I was myself again.

I’ve loved Matisse’s sensuous art ever since I first took an interest in painting, but never before have I fully appreciated this oft-quoted, oft-misunderstood remark of his: “What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter–a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.”

Art, of course, does many and various things. I doubt, though, that most people who have occasion to reflect on its myriad powers typically think first of its ability to console, to bring serenity to a troubled soul. I was in need of consolation today, and Matisse gave it to me.

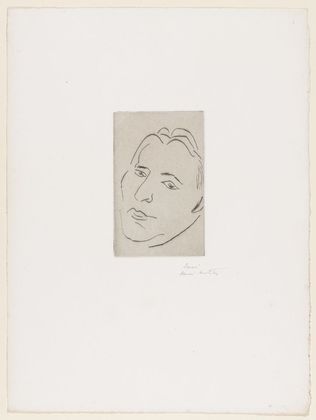

Quite a few of the works on paper included in “Matisse as Printmaker” will be familiar to those who know his work well, but one of them, a drypoint called “The Pianist Alfred Cortot,” was new to me. Cortot is one of my all-time favorite musicians, a recreative genius–no lesser word is strong enough–whose recorded performances of the music of Chopin, Schumann, Debussy, and Ravel are almost as important to me as the pieces themselves. He was also, I regret to say, a collabo who served as Vichy’s High Commissioner of Fine Arts and played in Nazi Germany, and that despicable fact will taint the memory of his artistry to the end of time. Yet the artistry itself was and is beyond question, and it is fascinating to see what Matisse made of Cortot’s characterful face in 1927, long before he chose to break bread with Hitler’s henchmen.

Quite a few of the works on paper included in “Matisse as Printmaker” will be familiar to those who know his work well, but one of them, a drypoint called “The Pianist Alfred Cortot,” was new to me. Cortot is one of my all-time favorite musicians, a recreative genius–no lesser word is strong enough–whose recorded performances of the music of Chopin, Schumann, Debussy, and Ravel are almost as important to me as the pieces themselves. He was also, I regret to say, a collabo who served as Vichy’s High Commissioner of Fine Arts and played in Nazi Germany, and that despicable fact will taint the memory of his artistry to the end of time. Yet the artistry itself was and is beyond question, and it is fascinating to see what Matisse made of Cortot’s characterful face in 1927, long before he chose to break bread with Hitler’s henchmen.

Would that art existed in a realm beyond such temporal horrors, but it does not and cannot. Yet it is still capable of lifting us out of the world, out of ourselves, and that is what “Matisse as Printmaker” did for me: it gave me solace and brought me a bit of peace on a troubled afternoon.

* * *

Alfred Cortot plays Ravel’s Sonatine:

Lookback: Woody Allen’s Pygmalion complex

From 2004, some thoughts on Woody Allen’s fixations:

On the surface, Annie Hall purports to tell the tale of how his peculiarities alienate the woman he loves, but its true subject matter is how their relationship actually makes Diane Keaton a better person. I suppose this must have been the first on-screen manifestation of Allen’s Pygmalion complex, which in Manhattan would explicitly reveal itself as an obsession with malleable young women. The trouble with such fixations, of course, is that even though the obsessed one grows inexorably older, the objects of his affection stay the same age–and we all know where that leads….

Read the whole thing here.

Almanac: Anthony Powell on teasing

“I found later that she was indeed what is called ‘a tease,’ perhaps the only outward indication that her inner life was not altogether happy; since there is no greater sign of innate misery than a love of teasing.”

Anthony Powell, At Lady Molly’s

TT: Almanac

“I found later that she was indeed what is called ‘a tease,’ perhaps the only outward indication that her inner life was not altogether happy; since there is no greater sign of innate misery than a love of teasing.”

Anthony Powell, At Lady Molly’s