“I’d given up offering advice. Even when people asked for it, they resented getting it.”

“I’d given up offering advice. Even when people asked for it, they resented getting it.”

Ross Macdonald, The Galton Case

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

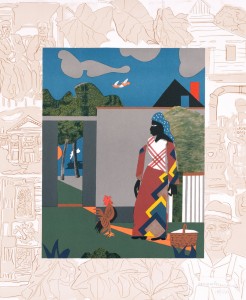

Mrs. T and I are thinking about adding another piece to the Teachout Museum, a lithograph by Romare Bearden, an artist whose work we both love, enough so that I’m surprised we’ve never before discussed the possibility of buying one of his prints. (Bearden is best remembered for his collages, but he was also a highly accomplished printmaker.) Though we already have a particular piece in mind, this isn’t something that we’ll do casually. Any art purchase, however modest the price, is by definition a big deal for us, and so we’re prepared to spend a considerable amount of time looking for just the right piece.

Mrs. T and I are thinking about adding another piece to the Teachout Museum, a lithograph by Romare Bearden, an artist whose work we both love, enough so that I’m surprised we’ve never before discussed the possibility of buying one of his prints. (Bearden is best remembered for his collages, but he was also a highly accomplished printmaker.) Though we already have a particular piece in mind, this isn’t something that we’ll do casually. Any art purchase, however modest the price, is by definition a big deal for us, and so we’re prepared to spend a considerable amount of time looking for just the right piece.

Needless to say, it’s a lot easier to collect art if you’re rich, but I doubt that it’s more fun. In fact, I suspect that the necessity to pinch our pennies may well enhance the pleasure that Mrs. T and I get out of spending them on a work of art. I spent several years tracking down an affordable copy of the Childe Hassam lithotint that we acquired last fall, but it was worth the wait, and then some.

Needless to say, it’s a lot easier to collect art if you’re rich, but I doubt that it’s more fun. In fact, I suspect that the necessity to pinch our pennies may well enhance the pleasure that Mrs. T and I get out of spending them on a work of art. I spent several years tracking down an affordable copy of the Childe Hassam lithotint that we acquired last fall, but it was worth the wait, and then some.

When I tweeted about all this last week, Aaron Haspel, a Twitter-based aphorist, responded as follows: “Taste is quality divided by expense. Limited means provide unlimited opportunity to show it.” I can’t put it any better than that. If you can afford to buy whatever you want whenever you want it, you’re a lot more likely to pull the trigger casually, and your purchases may not be as reflective of such taste as you have. Mrs. T and I can’t afford to do that. Whenever we buy and hang a piece of art in our New York apartment, it’s because we love it enough to make a financial sacrifice in order to have the pleasure of looking at it every day, and everything we purchase is a direct reflection of our deepest aesthetic values. We believe in our shared tastes.

It remains to be seen whether Romare Bearden will join the roster of artists for whom we’re willing to make such a sacrifice. If he does, though, you can be sure that we’ll both feel confident that we did the right thing.

“The world presents itself to me, not chiefly as a complex of visual sensations, but as a complex of aural sensations,” H.L. Mencken, himself a sometime music critic, once wrote. I’m far more aesthetically polydextrous (if that’s a word) than he was, but my long experience as a musician did make me so sensitive to what comes in through the ear that it may well amount to a kind of bias. I know, for instance, that it has a great deal to do with the way I respond to people in my daily life. At brunch yesterday, I was seated near a woman whose voice was so harsh and grating that it interfered with my ability to enjoy my meal….

Read the whole thing here.

Three years ago I posted an almanac entry drawn from an essay by L.E. Sissman called “The Constant Rereader’s Five-Foot Shelf”:

Three years ago I posted an almanac entry drawn from an essay by L.E. Sissman called “The Constant Rereader’s Five-Foot Shelf”:

A list of books that you reread is like a clearing in the forest: a level, clean, well-lighted place where you set down your burdens and set up your home, your identity, your concerns, your continuity in a world that is at best indifferent, at worst malign.

A reader of this blog has now invited me to draw up my own five-foot shelf of books that I like to reread. As I doubt I need to remind you, I turn to the novels of Raymond Chandler, William Haggard, Elmore Leonard, Patrick O’Brian, Rex Stout, Donald E. Westlake, and P.G. Wodehouse when I feel the urgent need to relax. Here is a shortish and by no means comprehensive list of other, more variously ambitious books to which I have also returned with fair regularity in recent years:

• Kingsley Amis, Girl, 20 and The Russian Girl

• Alan Ayckbourn, The Crafty Art of Playmaking

• Simon Callow, Charles Laughton: A Difficult Actor and Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu

• Truman Capote, In Cold Blood

• Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop

• James Gould Cozzens, By Love Possessed, Guard of Honor, and The Just and the Unjust

• Peter De Vries, The Blood of the Lamb

• The Film Criticism of Otis Ferguson

• Carl Flesch, Memoirs

• Gielgud’s Letters: John Gielgud in His Own Words

• Gielgud’s Letters: John Gielgud in His Own Words

• Moss Hart, Act One

• Hugh MacLennan, The Watch That Ends the Night

• All of the novels of John P. Marquand

• Somerset Maugham, Cakes and Ale, The Narrow Margin, and The Razor’s Edge

• Edwin O’Connor, All in the Family and The Edge of Sadness

• The Library of America’s Flannery O’Connor volume (very much including the letters)

• Richard Osborne, Herbert von Karajan: A Life in Music

• Anthony Powell, A Dance to the Music of Time

• Dawn Powell, The Locusts Have No King and A Time to Be Born

• All of the novels of Barbara Pym, but especially Excellent Women

• The Library of America’s Reporting World War II

• David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film

• Honor Tracy, The Straight and Narrow Path

• Anthony Trollope, The Way We Live Now

• Robert Penn Warren, All the King’s Men

• Evelyn Waugh, Sword of Honour

• Angus Wilson, Anglo-Saxon Attitudes

I make no claim, by the way, that all of these books are “classic,” or that I think they’re better than other books that I reread less often (or not at all). They are nothing more—or less—than books that I like to reread fairly often for reasons that are in some cases not entirely clear to me. Make of that what you will.

New York City Ballet performs George Balanchine’s Symphony in C in 1973. The soloists are Karin von Aroldingen and Jean-Pierre Bonnefous in the first movement, Allegra Kent and Conrad Ludlow in the second movement, Sara Leland and John Clifford in the third movement, and Marnee Morris in the finale. The score is Georges Bizet’s Symphony in C, composed shortly after Bizet turned seventeen:

New York City Ballet performs George Balanchine’s Symphony in C in 1973. The soloists are Karin von Aroldingen and Jean-Pierre Bonnefous in the first movement, Allegra Kent and Conrad Ludlow in the second movement, Sara Leland and John Clifford in the third movement, and Marnee Morris in the finale. The score is Georges Bizet’s Symphony in C, composed shortly after Bizet turned seventeen:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

“‘The point is,’ cutting off Gustav’s usually indignant scream, ‘a person feels good listening to Rossini. All you feel like listening to Beethoven is going out and invading Poland. Ode to Joy indeed. The man didn’t even have a sense of humor. I tell you,’ shaking his skinny old fist, ‘there is more of the Sublime in the snare-drum part of La Gazza Ladra than in the whole Ninth Symphony. With Rossini, the whole point is that lovers always get together, isolation is overcome, and like it or not that is the one great centripetal movement of the World. Through the machineries of greed, pettiness, and the abuse of power, love occurs. All the shit is transmuted to gold. The walls are breached, the balconies are scaled—listen!’”

“‘The point is,’ cutting off Gustav’s usually indignant scream, ‘a person feels good listening to Rossini. All you feel like listening to Beethoven is going out and invading Poland. Ode to Joy indeed. The man didn’t even have a sense of humor. I tell you,’ shaking his skinny old fist, ‘there is more of the Sublime in the snare-drum part of La Gazza Ladra than in the whole Ninth Symphony. With Rossini, the whole point is that lovers always get together, isolation is overcome, and like it or not that is the one great centripetal movement of the World. Through the machineries of greed, pettiness, and the abuse of power, love occurs. All the shit is transmuted to gold. The walls are breached, the balconies are scaled—listen!’”

Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow (courtesy of Tim Page)

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I report on the first installment of the Amy Herzog Festival currently being presented by Baltimore’s Center Stage, a revival of After the Revolution. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

What does a young playwright have to do in order to be thought important? At 36, Amy Herzog appears to be well on her way to filling the bill. Though she has yet to make it to Broadway or win a Pulitzer, Herzog has written four plays that have been produced in New York and are currently being performed from coast to coast. Now Baltimore’s Center Stage, one of America’s leading regional companies, is mounting an “Amy Herzog Festival” in which her most successful plays, “After the Revolution” and “4000 Miles,” will be presented in repertory in productions directed by Lila Neugebauer. It’s the first time that the two plays, which share a central character and a common theme, have been done together.

What does a young playwright have to do in order to be thought important? At 36, Amy Herzog appears to be well on her way to filling the bill. Though she has yet to make it to Broadway or win a Pulitzer, Herzog has written four plays that have been produced in New York and are currently being performed from coast to coast. Now Baltimore’s Center Stage, one of America’s leading regional companies, is mounting an “Amy Herzog Festival” in which her most successful plays, “After the Revolution” and “4000 Miles,” will be presented in repertory in productions directed by Lila Neugebauer. It’s the first time that the two plays, which share a central character and a common theme, have been done together.

Such an occasion is a clear sign of potential top-tier stature—and “After the Revolution,” the 2010 play that initially brought Ms. Herzog wider attention, is worthy of the treatment that Center Stage is giving it. Of all the new plays that I’ve reviewed in this space, “After the Revolution” is one of the half-dozen that impressed me most on first viewing, and it’s just as good the second time around.

Life is forever handing juicy plots to writers, but what they do with them is something else again. Ms. Herzog found out in 1999 that Julius Joseph, her father’s stepfather, had been a Soviet spy during World War II. (His code name was “Cautious.”) What she did with that knowledge was spin it into a play about a fictional “red-diaper” family whose senior members all have long-standing ties to the Communist Party. Emma Joseph (Ashton Heyl), the central character, is a priggish young political activist who is stunned by the revelation that Joe Joseph, her late grandfather, who lost his job in the ‘50s because of his party membership and became a progressive martyr, spied for the Russians and lied to Congress about it. Worse yet, the rest of her family, including Vera (Lois Markle), Emma’s beloved grandmother, knew all along—and lied to her about it…..

What is most striking about “After the Revolution” is that Ms. Herzog has dissected the follies of the Josephs not with splenetic outrage but with cool, crisp detachment. Her dialogue glitters with the knowing wit of a sharp-eyed observer familiar with all the ins and outs of the cozy milieu about which she writes. And while no one gets off easy, least of all the chokingly earnest Emma, Ms. Herzog makes us laugh at her characters instead of stooping to preachiness—which adds to the climactic force with which she finds them all, Emma included, guilty of complacency in the first degree.

Ms. Neugebauer, who directed the Signature Theatre Company’s excellent 2014 revival of A.R. Gurney’s “The Wayside Motor Inn,” has staged “After the Revolution” with identical skill. Under her sensitive guidance, Center Stage’s first-rate cast appears to be not an ensemble but a flesh-and-blood family whose members are joined at the hip by love and frustration—and anger….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Scenes from Playwrights Horizon’s 2010 New York premiere of After the Revolution:

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog