“A man who waits to believe in action before acting is anything you like, but he’s not a man of action. It is as if a tennis player before returning a ball stopped to think about his views of the physical and mental advantages of tennis. You must act as you breathe.”

“A man who waits to believe in action before acting is anything you like, but he’s not a man of action. It is as if a tennis player before returning a ball stopped to think about his views of the physical and mental advantages of tennis. You must act as you breathe.”

Georges Clemenceau, Clemenceau, The Events of His Life as Told by Himself to His Former Secretary, Jean Martet (trans. Milton Waldman)

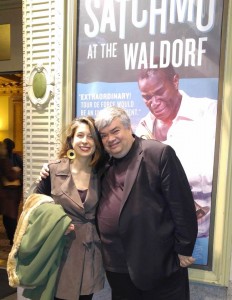

Satchmo at the Waldorf

Satchmo at the Waldorf  It feels strange to leave Satchmo behind, but it’s also something of a relief. Even when it goes well—perhaps especially when it goes well—opening a show out of town can be a lonely business. To be sure, I have old friends in Chicago and San Francisco who were kind enough to keep me company there, and I also love the wonderful new friends that I’ve made at American Conservatory Theater and the Court. Yet I missed Mrs. T fiercely during my long trek through the time zones, and by the time it was over, I was bone-tired of living out of a carry-on bag and never being quite sure when to go to bed.

It feels strange to leave Satchmo behind, but it’s also something of a relief. Even when it goes well—perhaps especially when it goes well—opening a show out of town can be a lonely business. To be sure, I have old friends in Chicago and San Francisco who were kind enough to keep me company there, and I also love the wonderful new friends that I’ve made at American Conservatory Theater and the Court. Yet I missed Mrs. T fiercely during my long trek through the time zones, and by the time it was over, I was bone-tired of living out of a carry-on bag and never being quite sure when to go to bed. Am I going to miss Satchmo at the Waldorf? I already do. How could I not? A

Am I going to miss Satchmo at the Waldorf? I already do. How could I not? A

Ms. Lavin, the nominal star of the show, plays a physically attractive but “warm-cold” woman who has kept her children at arm’s length throughout her life. She is dissected by Seth in a stream of one-liners that have the sharp sting of well-remembered truth: “She had a tendency to pose…She was nostalgic but not for anything that had ever happened…She said five or six witty things, then repeated them.” The painfully inhibited Seth, who is enraged by Anna’s “decades of benign neglect,” is an even more striking character. A failed violist turned (unwillingly) celibate obituary writer, he is as disappointed with himself as Anna is disappointed with him: ”I’m…limited. One runs out of me quickly.” “Our Mother’s Brief Affair” gets all these things right, and the fact that Seth is a writer by trade justifies his quick-draw quippery. You buy him as a person—and you feel for him.

Ms. Lavin, the nominal star of the show, plays a physically attractive but “warm-cold” woman who has kept her children at arm’s length throughout her life. She is dissected by Seth in a stream of one-liners that have the sharp sting of well-remembered truth: “She had a tendency to pose…She was nostalgic but not for anything that had ever happened…She said five or six witty things, then repeated them.” The painfully inhibited Seth, who is enraged by Anna’s “decades of benign neglect,” is an even more striking character. A failed violist turned (unwillingly) celibate obituary writer, he is as disappointed with himself as Anna is disappointed with him: ”I’m…limited. One runs out of me quickly.” “Our Mother’s Brief Affair” gets all these things right, and the fact that Seth is a writer by trade justifies his quick-draw quippery. You buy him as a person—and you feel for him. •

•