A couple of years ago I blogged about making a will:

It took me two days to figure out who was to get what. By the time I was done, I felt so ceremonial that I started drawing up a list of music to be played at my funeral. At that point my sense of humor finally kicked in…

I’ve scrapped my plans for the Terry Teachout Memorial Concert. Should a pianist happen to be present when the time comes, I’d like her to play Aaron Copland’s Down a Country Lane. (Remember that, Heather.) The rest I’ll leave to whoever is in charge of disposing of my earthly remains, with the caveat that she keep it simple. I’ve never cared for funerals, nor do I wish to burden my friends with the chore of attending an elaborate one.

Since then I’ve had Down a Country Lane played at my wedding, thus rendering it unacceptable for mortuary purposes, and last week I attended a very elaborate memorial service in which classical music figured prominently. As I listened to the St. Patrick’s Cathedral Choir sing Palestrina and Victoria, it suddenly occurred to me that The Letter, the opera that Paul Moravec and I are writing, contains an aria whose suitability for funereal occasions is self-evident. It is a lament that one of the characters sings for her dead lover: I am alone,/Lost, lost/In the dark, silent night,/Looking only for light.

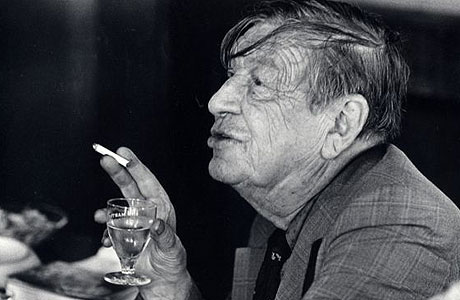

Would it be too outrageously immodest to request that an aria you had written be sung at your own funeral? No more so, surely, than the last musical request of W.H. Auden, an opera buff with a sense of humor: “When my time is up, I want Siegfried’s Funeral March and not a dry eye in the house.” (He got his wish.) Alas, our aria is a bit too dramatic to be wholly appropriate to such an occasion. It would be nice to have one of Paul’s pieces played, though, and I can think of two songs that would be just as appropriate, Copland’s “The World Feels Dusty” (from Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson) and Benjamin Britten’s “The Choirmaster’s Burial” (from Winter Words, a song cycle on poems by Thomas Hardy). Both are near to my heart, and it is pleasing to imagine them being sung to a group of friends gathered to see me off.

Would it be too outrageously immodest to request that an aria you had written be sung at your own funeral? No more so, surely, than the last musical request of W.H. Auden, an opera buff with a sense of humor: “When my time is up, I want Siegfried’s Funeral March and not a dry eye in the house.” (He got his wish.) Alas, our aria is a bit too dramatic to be wholly appropriate to such an occasion. It would be nice to have one of Paul’s pieces played, though, and I can think of two songs that would be just as appropriate, Copland’s “The World Feels Dusty” (from Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson) and Benjamin Britten’s “The Choirmaster’s Burial” (from Winter Words, a song cycle on poems by Thomas Hardy). Both are near to my heart, and it is pleasing to imagine them being sung to a group of friends gathered to see me off.

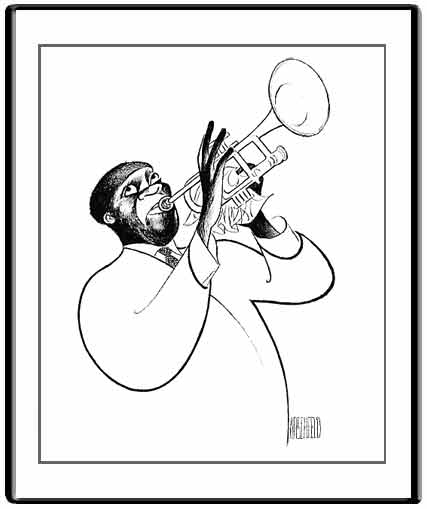

Needless to say, I couldn’t imagine departing this life without the assistance of Louis Armstrong, who in 1950 obligingly made a wonderful recording called New Orleans Function in which he, Barney Bigard, Cozy Cole, Earl Hines, Arvell Shaw, and Jack Teagarden recreate an old-time jazz funeral. In addition to playing trumpet, Armstrong supplies the gleeful narration: “And now, folks, we gonna take you down to New Or-leans, Loosiana. Tell you the story about ‘Didn’t He Ramble.’ ‘Course you know there was a funeral march in front of ‘Didn’t He Ramble,’ where they take the body to the cemetery and they lower ol’ Brother Gate in the ground. And, uh…dig it!” I think that would fit in quite nicely after “The Choirmaster’s Burial,” don’t you?

Needless to say, I couldn’t imagine departing this life without the assistance of Louis Armstrong, who in 1950 obligingly made a wonderful recording called New Orleans Function in which he, Barney Bigard, Cozy Cole, Earl Hines, Arvell Shaw, and Jack Teagarden recreate an old-time jazz funeral. In addition to playing trumpet, Armstrong supplies the gleeful narration: “And now, folks, we gonna take you down to New Or-leans, Loosiana. Tell you the story about ‘Didn’t He Ramble.’ ‘Course you know there was a funeral march in front of ‘Didn’t He Ramble,’ where they take the body to the cemetery and they lower ol’ Brother Gate in the ground. And, uh…dig it!” I think that would fit in quite nicely after “The Choirmaster’s Burial,” don’t you?

This is not to say that I’ve changed my mind about the remainder of the ceremony. “What I’d like,” I wrote in 2006, “is for the thirty-odd friends to whom I’m leaving the Teachout Museum to gather at my apartment, drink a toast, strip the walls, then go home and hang up their booty. That’s my kind of funeral–complete with party favors.” I still stand by that….

But of course I’m being silly. No act is so vain–in every sense of the word–as planning your own funeral. Vain and a little bit sad, and sometimes very sad indeed. One of the characters in The Edge of Sadness, Edwin O’Connor’s beautiful 1961 novel about an alcoholic parish priest, is a dried-up old Irish immigrant who spends his uncrowded days planning his funeral in excruciatingly exact detail. The priest listens patiently and with amusement, for he knows quite well what Bucky Heffernan is up to:

Bucky brought a peculiar zest, a flavor, to the day, and if much of his talk meant nothing at all…there was a kind of fascination in listening to a man who could with such enthusiasm and in such detail outline the blueprint for his posthumous disposition, and who could see in his own grave nothing short of a civic monument. But beyond all this there was something else, something which did not belong in never-never land–not a dream or an antic fantasy, but a fact which belonged to the here and now. This was the plain fact of death itself, the sober side of the picture, which I sometimes forgot even existed as I listened to Bucky, but which–I’m convinced–he never forgot, not even for an instant. Because every once in a while, as he talked, underneath all the complicated and grandiose plans, I caught a note of uncertainty and fear, and after a time I was sure that this was what he was really talking about, and not at all the burial or the dramatic transfer of his bones. I may have been all wrong in this, reading too much into a tone or a look in the eye, but I don’t think so, and in any case the least I could do was to listen.

When I looked up this passage in my battered old copy of The Edge of Sadness the other day, I found tucked among the pages a yellowed newspaper clipping from my hometown newspaper, a four-inch obituary of one of the friends of my youth. Greg Tanner was forty-one when he died in a car crash in 1996, leaving behind a wife and two children. The Smalltown Standard-Democrat summed up his too-short life in six no-nonsense paragraphs, and two days later he was buried in a country cemetery in southeast Missouri. So far as I know, nobody sang at his graveside, even though he loved music and played a mean fiddle.

Greg and I were close–I wrote about him in my first book–but it had been quite some time since I’d last thought of him, and I suspect that a similar interval will pass before I have occasion to think of him again. Few of us are destined to be remembered very clearly or very often, save by our nearest and dearest. We know this in our bones, which is why some monied folk seek to elude the anonymity of the ever-beckoning grave by pasting their names on concert halls or museum wings. For those of us who have done less well in life’s lottery, there is always the elaborately planned funeral.

Me, I’m giving away the pieces in the Teachout Museum, and perhaps the friends who are my legatees will hang their bequests on their living-room walls and think of me whenever they look at them. But even if they forget to remember (and they will, they will!), at least they will be in the life-enhancing presence of something I once thought beautiful. I can think of worse monuments.

•

•  • The death of Gene Puerling has yet to attract the attention of the increasingly culturally illiterate New York Times, but the

• The death of Gene Puerling has yet to attract the attention of the increasingly culturally illiterate New York Times, but the  It’s been quite a while since I walked through Rockefeller Center, even longer since I crossed Fifth Avenue and went inside St. Patrick’s, and a very long time indeed since I last attended a memorial service for a public figure. For all these reasons, I have no standard against which to measure Bill’s funeral obsequies. All I can tell you was that today’s service seemed as splendid as it could possibly have been. The cathedral was full of mourners, the choir loft full of singers, and the music was mostly appropriate to the occasion. Bill was a serious amateur musician who loved Bach above all things–he actually performed the F Minor Harpsichord Concerto in public on more than one occasion–so the organist played “Sheep May Safely Graze” and the slow movement of the Toccata, Adagio, and Fugue in C Major. No less suitable were the sung portions of the Mass, drawn from Victoria’s sweetly austere Missa “O magnum mysterium,” and the closing hymn, the noble tune from Gustav Holst’s The Planets to which the following words were later set: I vow to thee, my country–all earthly things above–/Entire and whole and perfect, the service of my love.

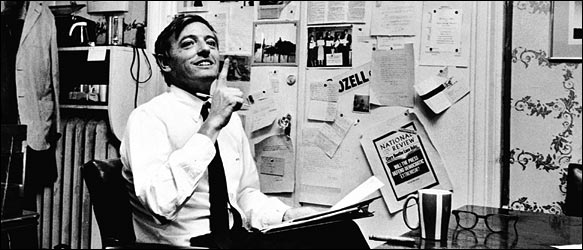

It’s been quite a while since I walked through Rockefeller Center, even longer since I crossed Fifth Avenue and went inside St. Patrick’s, and a very long time indeed since I last attended a memorial service for a public figure. For all these reasons, I have no standard against which to measure Bill’s funeral obsequies. All I can tell you was that today’s service seemed as splendid as it could possibly have been. The cathedral was full of mourners, the choir loft full of singers, and the music was mostly appropriate to the occasion. Bill was a serious amateur musician who loved Bach above all things–he actually performed the F Minor Harpsichord Concerto in public on more than one occasion–so the organist played “Sheep May Safely Graze” and the slow movement of the Toccata, Adagio, and Fugue in C Major. No less suitable were the sung portions of the Mass, drawn from Victoria’s sweetly austere Missa “O magnum mysterium,” and the closing hymn, the noble tune from Gustav Holst’s The Planets to which the following words were later set: I vow to thee, my country–all earthly things above–/Entire and whole and perfect, the service of my love. Indeed he did not: Bill was the least weltschmerzy person imaginable. Henry Kissinger, who eulogized him this morning, alluded to that side of Bill’s personality when he remarked that Bill “was vouchsafed a little miracle: to enjoy so much what was compelled by inner necessity.” I couldn’t have put it better. Bill worked fearfully hard and was deadly serious about what he believed, but he extracted self-evident enjoyment from everything he did, and you couldn’t be in his presence for more than a minute or two without responding to his joie de vivre. If I’d been in charge of the music today, I would have made a point of picking something a good deal more festive–Bach’s Fugue à la gigue, say, or one of the harpsichord sonatas in which Scarlatti turned Bill’s favorite instrument into a giant super-guitar.

Indeed he did not: Bill was the least weltschmerzy person imaginable. Henry Kissinger, who eulogized him this morning, alluded to that side of Bill’s personality when he remarked that Bill “was vouchsafed a little miracle: to enjoy so much what was compelled by inner necessity.” I couldn’t have put it better. Bill worked fearfully hard and was deadly serious about what he believed, but he extracted self-evident enjoyment from everything he did, and you couldn’t be in his presence for more than a minute or two without responding to his joie de vivre. If I’d been in charge of the music today, I would have made a point of picking something a good deal more festive–Bach’s Fugue à la gigue, say, or one of the harpsichord sonatas in which Scarlatti turned Bill’s favorite instrument into a giant super-guitar. “South Pacific” goes dead in the water every time the characters stop singing and start talking, which is way too often. The book, adapted by Hammerstein and Joshua Logan from James Michener’s “Tales of the South Pacific,” is a wartime drama built around a May-September romance between Nellie Forbush (Ms. O’Hara), a cheery Navy nurse, and Emile de Becque (Paulo Szot), a super-suave French plantation owner who fled to a Polynesian island after killing a man, took up with a now-deceased native woman and sired an adorable pair of children. Their skins, alas, are too brown to suit the Arkansas-born Nellie, and thereby hangs the tale of “South Pacific.” Will true love purge our poor benighted heroine of her racism? Will her middle-aged suitor be killed in a daredevil mission behind Japanese lines? Would that one could care, but Hammerstein preaches his sermon with head-thumping triteness: You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late/Before you are six or seven or eight/To hate all the people your relatives hate. Stir in a megadose of beat-the-Japs period fervor, and you get a show so reeking of uplift that you can all but feel your pulse slowing to a crawl as the second act inches toward its predestined happy ending.

“South Pacific” goes dead in the water every time the characters stop singing and start talking, which is way too often. The book, adapted by Hammerstein and Joshua Logan from James Michener’s “Tales of the South Pacific,” is a wartime drama built around a May-September romance between Nellie Forbush (Ms. O’Hara), a cheery Navy nurse, and Emile de Becque (Paulo Szot), a super-suave French plantation owner who fled to a Polynesian island after killing a man, took up with a now-deceased native woman and sired an adorable pair of children. Their skins, alas, are too brown to suit the Arkansas-born Nellie, and thereby hangs the tale of “South Pacific.” Will true love purge our poor benighted heroine of her racism? Will her middle-aged suitor be killed in a daredevil mission behind Japanese lines? Would that one could care, but Hammerstein preaches his sermon with head-thumping triteness: You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late/Before you are six or seven or eight/To hate all the people your relatives hate. Stir in a megadose of beat-the-Japs period fervor, and you get a show so reeking of uplift that you can all but feel your pulse slowing to a crawl as the second act inches toward its predestined happy ending.