Orson Welles reads the opening section of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“All truth is profound.”

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

HEARING IS BELIEVING

“What can we learn from the voices of famous writers? Sometimes they inadvertently tell us things that we suspected but never knew for sure. Hearing Raymond Chandler’s mousy voice left me certain that he created the stalwart yet sensitive Marlowe as an act of wish fulfillment, allowing him to ‘do’ on paper what he would never have dared do in real life…”

TT: Scene stealing (II)

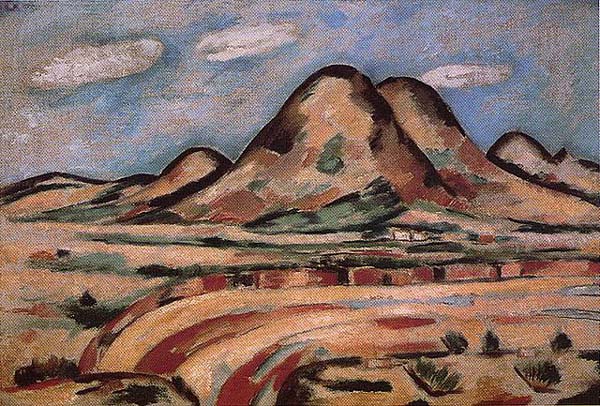

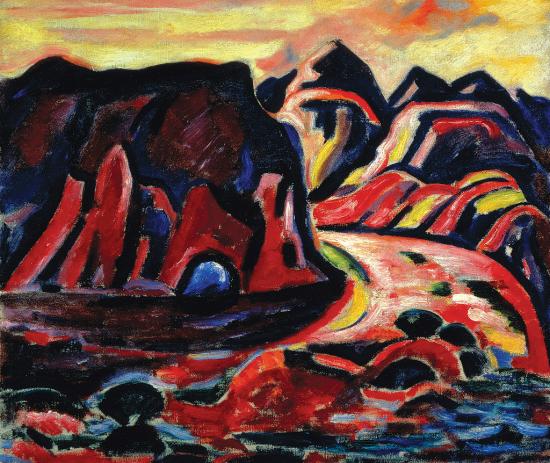

Richard Diebenkorn wasn’t the only modern American painter to have been stirred by the New Mexico landscape. It hit Marsden Hartley just as hard. “I want to paint the livingness of appearances,” Hartley said. He did just that when he came to Santa Fe in 1918, often to unforgettable effect.

Richard Diebenkorn wasn’t the only modern American painter to have been stirred by the New Mexico landscape. It hit Marsden Hartley just as hard. “I want to paint the livingness of appearances,” Hartley said. He did just that when he came to Santa Fe in 1918, often to unforgettable effect.

I can’t help but wonder what Hartley, who died in 1943, would have thought of the Santa Fe Opera‘s mesa-top theater, which opened its doors a decade ago. As eye-catching as it is, the Crosby Theater doesn’t stand out from the surrounding countryside so much as it blends into its complex contours. The open-air theater was oriented on the mesa in such a way as to allow directors and designers to use the desert sunset as a natural backdrop to the company’s productions, and the famously mercurial local weather–thunderstorms can blow up without warning–has been known to add an extra touch of drama.

The sensitivity with which the Crosby Theater was integrated into the Santa Fe landscape both reassured me and helped to teach me a lesson. How can the librettist and composer of a new opera, even one as action-packed as The Letter, hope to compete with thunderstorms and mountain ranges? As I watched the Santa Fe Opera perform The Marriage of Figaro, Falstaff, and Billy Budd, it occurred to me that opera is capable of “competing” on even terms with the most awe-inspiring of natural spectacles, since its subject matter–the passions of man–is no less inherently awesome.

The sensitivity with which the Crosby Theater was integrated into the Santa Fe landscape both reassured me and helped to teach me a lesson. How can the librettist and composer of a new opera, even one as action-packed as The Letter, hope to compete with thunderstorms and mountain ranges? As I watched the Santa Fe Opera perform The Marriage of Figaro, Falstaff, and Billy Budd, it occurred to me that opera is capable of “competing” on even terms with the most awe-inspiring of natural spectacles, since its subject matter–the passions of man–is no less inherently awesome.

Taking his cue from the fact that Paul Moravec and I have lately taken to calling The Letter an “opera noir,” Mark Tiarks, the Santa Fe Opera’s head of planning and marketing, wrote the following blurb for this year’s souvenir program:

Special delivery from composer Paul Moravec and librettist Terry Teachout: a hard-boiled dame cooks up her own little Singapore fling. Her double-crossing lover gets a lethal dose of lead as a lovely parting gift. Her sap of a husband helps her get away with murder. Almost…

Opera’s classic ingredients–lust, adultery, and revenge–are dished up noir style in this world premiere production. The Letter will be conducted by Patrick Summers and staged by Jonathan Kent, with scenery by Hildegard Bechtler and costumes by Tom Ford. Patricia Racette stars as the venomous Leslie Crosbie, Anthony Michaels-Moore plays her husband, and James Maddalena is their ethically challenged lawyer.

That’s a knowing and clever school-of-Chandler pastiche, and I was pleased to see it on the poster announcing the Santa Fe Opera’s 2009 season. On the other hand, I wouldn’t want anyone to get the idea that The Letter is, in the oft-quoted phrase with which Joseph Kerman amusingly (and wrongly) dismissed Tosca, a “shabby little shocker.” Paul and I have gone to considerable trouble to heighten the emotional climate of the play by Somerset Maugham on which our opera is based, in the process turning it from a neatly turned thriller into a full-fledged piece of lyric theater. Our characters, unlike Maugham’s, are concerned not just with their own desires but with the state of their souls.

In the words of Howard Joyce, the troubled lawyer in The Letter who’ll be played by Jim Maddalena:

I’ve lost my way in the jungle,

A way I knew when I was young,

When I thought I knew the truth.

But what is truth?

What is right?

What is love?

And where, where is the light?

None of Maugham’s characters asks such questions of himself, at least not out loud. In our version of The Letter, by contrast, they are the heart of the matter, and there is nothing shabby or small about them. We are never bigger than when we grapple, however vainly, with the ultimate mysteries, of which none is more profound–or impenetrable–than the mystery of love.

Would that I were a poet or a philosopher, but I’m only a critic! Still, I like to think that the powerful and ennobling music to which Paul set my simple words has made them worthy to be sung in a place like the Crosby Theater. If Maugham’s play were to be performed there, by contrast, it would probably seem very small indeed, just as its cynical characters would be dwarfed by their physical surroundings. That’s the difference between a well-made play and a work of lyric theater: one is about men, the other about man.

Would that I were a poet or a philosopher, but I’m only a critic! Still, I like to think that the powerful and ennobling music to which Paul set my simple words has made them worthy to be sung in a place like the Crosby Theater. If Maugham’s play were to be performed there, by contrast, it would probably seem very small indeed, just as its cynical characters would be dwarfed by their physical surroundings. That’s the difference between a well-made play and a work of lyric theater: one is about men, the other about man.

I am, of course, claiming a lot for Paul’s music, but I do so unhesitatingly: I believe without reservation in his great gifts. He’s not so sure. “Am I really ready to play in this league?” he asked me at the intermission of Billy Budd, and he meant it.

“You’d better believe it, pal,” I replied, and I meant it, too.

Mind you, I sympathized with Paul’s qualms. Not only is Budd one of the half-dozen best operas of the twentieth century, but The Marriage of Figaro and Falstaff are very possibly the two greatest operas ever written. Next summer The Letter will be sharing the stage with Don Giovanni and La Traviata, both of which are strong contenders for the same top honors. Britten, Mozart, and Verdi at their best–or even their second-best–are hard acts to follow, and only a halfwit would feel other than anxious at the thought of seeing his first opera premiered under such daunting circumstances.

Yet that didn’t stop us from writing The Letter, nor should it have done so. Whatever else we are or aren’t, Paul and I are honest craftsmen. We’ve done our best to make The Letter good, and we have no doubt that the Santa Fe Opera will do its best to make us look good. The company has already put together the best of all possible casts and production teams, starting with Patricia Racette, who was our first and only choice to create the role of Leslie Crosbie, the desperate anti-heroine of The Letter. I’ve admired Pat from afar ever since I reviewed her first Violetta at the Metropolitan Opera for the New York Daily News a decade ago. Now, much to my surprise, I’m working with her, and the experience is even more gratifying than I’d imagined it would be.

Yet that didn’t stop us from writing The Letter, nor should it have done so. Whatever else we are or aren’t, Paul and I are honest craftsmen. We’ve done our best to make The Letter good, and we have no doubt that the Santa Fe Opera will do its best to make us look good. The company has already put together the best of all possible casts and production teams, starting with Patricia Racette, who was our first and only choice to create the role of Leslie Crosbie, the desperate anti-heroine of The Letter. I’ve admired Pat from afar ever since I reviewed her first Violetta at the Metropolitan Opera for the New York Daily News a decade ago. Now, much to my surprise, I’m working with her, and the experience is even more gratifying than I’d imagined it would be.

With Pat, Jim, and Anthony on stage, Jonathan at the helm, and Hildegard and Tom designing the set and costumes, I think it’s fair to expect that the premiere of The Letter will be worth seeing and hearing. That’s as far as I’m prepared to go–but it’s far enough for me.

(Second of two parts)

TT: Almanac

“This mesa plain had an appearance of great antiquity, and of incompleteness; as if, with all the materials for world-making assembled, the Creator had desisted, gone away and left everything on the point of being brought together, on the eve of being arranged into mountain, plain, plateau. The country was still waiting to be made into a landscape.”

Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop

TT: Scene stealing (I)

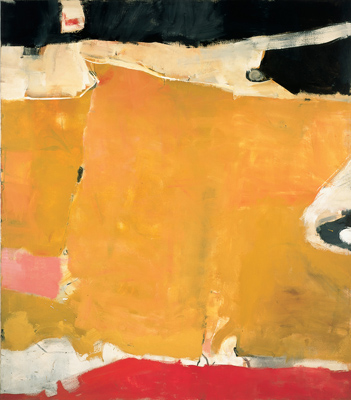

Last week I got drunk on the New Mexico landscape, at once violent and austere, colorful and stark, framed by soaring mountain ranges and a vast blue bowl of sky. It is an aesthete’s delight and an artist’s despair, for its beauty is so breathtaking as to defy the power of mere mortals to suggest, though countless artists have done what they could to convey its quality. Richard Diebenkorn did better than most when he painted a series of landscape-inspired abstract canvases in Albuquerque between 1950 and 1952, many of which are currently on view at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. and one of which is reproduced on the cover of the Santa Fe Opera‘s 2008 souvenir program. (I saw it when the Phillips exhibition was on display in New York a few months ago.)

Last week I got drunk on the New Mexico landscape, at once violent and austere, colorful and stark, framed by soaring mountain ranges and a vast blue bowl of sky. It is an aesthete’s delight and an artist’s despair, for its beauty is so breathtaking as to defy the power of mere mortals to suggest, though countless artists have done what they could to convey its quality. Richard Diebenkorn did better than most when he painted a series of landscape-inspired abstract canvases in Albuquerque between 1950 and 1952, many of which are currently on view at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. and one of which is reproduced on the cover of the Santa Fe Opera‘s 2008 souvenir program. (I saw it when the Phillips exhibition was on display in New York a few months ago.)

The best of these paintings do more than hint at what Willa Cather had in mind when she wrote about New Mexico in Death Comes for the Archbishop:

From the flat red sea of sand rose great rock mesas, generally Gothic in outline, resembling vast cathedrals. They were not crowded together in disorder, but placed in wide spaces, long vistas between. This plain might once have been an enormous city, all the smaller quarters destroyed by time, only the public buildings left,–piles of architecture that were like mountains. The sandy soil of the plain had a light sprinkling of junipers, and was splotched with masses of blooming rabbit brush,–that olive-coloured plant that grows in high waves like a tossing sea, at this season covered with a thatch of bloom, yellow as gorse, or orange like marigolds.

I didn’t get to see much of New Mexico when I flew out to Santa Fe two months ago to attend the press conference at which the cast and production team for the premiere of The Letter were announced. I had to race back to Manhattan the next day to cover a Broadway opening, so I ended up spending a grand total of sixteen hours in Santa Fe, more than half of them in darkness. Even then, though, I wondered whether the work that Paul Moravec and I are writing for the Santa Fe Opera would be upstaged by the countryside that surrounds the 2,128-seat outdoor theater where the company performs each summer–not to mention the theater itself, whose architectural design is a perfect complement to the 7,500-foot-high mesa atop which it sits.

I didn’t get to see much of New Mexico when I flew out to Santa Fe two months ago to attend the press conference at which the cast and production team for the premiere of The Letter were announced. I had to race back to Manhattan the next day to cover a Broadway opening, so I ended up spending a grand total of sixteen hours in Santa Fe, more than half of them in darkness. Even then, though, I wondered whether the work that Paul Moravec and I are writing for the Santa Fe Opera would be upstaged by the countryside that surrounds the 2,128-seat outdoor theater where the company performs each summer–not to mention the theater itself, whose architectural design is a perfect complement to the 7,500-foot-high mesa atop which it sits.

Paul and I have just spent four full days and nights in Santa Fe, long enough for me to look around town in between shows and get something of a feel for the place where the Santa Fe Opera makes its home. Most of our time, though, was spent at the “ranch” at the end of Opera House Drive, where we conferred with many of the people who will be helping to put The Letter on stage next July and spent our evenings watching the company at work.

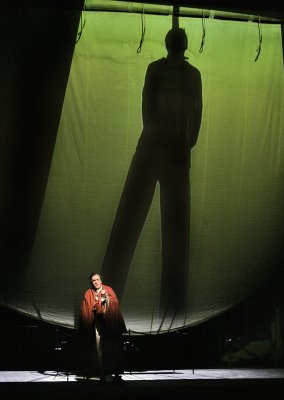

Now that I’ve finally seen the Santa Fe Opera perform, I feel reasonably confident that The Letter won’t get lost amid the surrounding scenery–in part because the man-made scenery I saw last week was so remarkable. Robert Innes Hopkins’ set for Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd, most of which takes place on the main-deck and quarter-deck of H.M.S. Indomitable, is a spectacular piece of naturalistic design tinged with expressionism, and the sets for The Marriage of Figaro (by Paul Brown) and Falstaff (by Allen Moyer) are slightly less sensational but no less impressive or effective. I am, to be sure, a biased witness, but the productions as a whole seemed to me as good as any I’d seen anywhere, while Billy Budd, staged by Paul Curran, was the best Budd I’ve ever seen, period.

Now that I’ve finally seen the Santa Fe Opera perform, I feel reasonably confident that The Letter won’t get lost amid the surrounding scenery–in part because the man-made scenery I saw last week was so remarkable. Robert Innes Hopkins’ set for Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd, most of which takes place on the main-deck and quarter-deck of H.M.S. Indomitable, is a spectacular piece of naturalistic design tinged with expressionism, and the sets for The Marriage of Figaro (by Paul Brown) and Falstaff (by Allen Moyer) are slightly less sensational but no less impressive or effective. I am, to be sure, a biased witness, but the productions as a whole seemed to me as good as any I’d seen anywhere, while Billy Budd, staged by Paul Curran, was the best Budd I’ve ever seen, period.

I was especially interested in Figaro because it was directed by Jonathan Kent, who will be staging The Letter, and Falstaff because the title role is currently being sung by Anthony Michaels-Moore, one of the stars of our opera. Anthony has been cast as Robert Crosbie, the cuckolded husband who was played by Herbert Marshall in William Wyler’s 1940 film version of the Somerset Maugham play on which The Letter is based.

I last saw Anthony at the Metropolitan Opera House earlier this season–he was singing Balstrode in Britten’s Peter Grimes–and I was amazed to discover on Tuesday that among his myriad gifts, he can be funny. Not that he’ll be cracking jokes in The Letter, but comedy, as everyone knows, is harder to play than tragedy, and Anthony pulled it off with awesome aplomb. “It’s the fat suit, really,” he modestly told me the day after his debut. “When you put it on, something happens.” Maybe, but there has to be something there in the first place, and that mysterious “something” is very much there in in Anthony’s case.

As for Jonathan Kent’s Figaro, it’s obviously not for me to praise the work of the man who’ll be directing The Letter. Instead I’ll quote from my Wall Street Journal review of the 2006 Broadway revival of Brian Friel’s Faith Healer, which I wrote many months before I knew that I would be working with Jonathan:

The original Broadway production of “Faith Healer,” which starred James Mason, ran for just 20 performances. I didn’t see it then and so can say nothing about its initial failure to hold the stage. Perhaps a quarter-century’s worth of one-person shows has awakened New York playgoers to the theatrical power of the extended monologue. Whatever the reason, this revival is making an overwhelmingly powerful impression on the audiences who see it, as well it should.

For my part, I came away humbled by the collective mastery of the artists who are bringing “Faith Healer” to blazing life each night. Gifted as they are, though, it is Brian Friel who deserves the highest praise of all. Once again he has proved art’s power to narrow the fearful gap that separates soul from soul. Like every great writer, he reveals us to one another–and to ourselves.

The preview of Faith Healer that I saw was one of the most unforgettable nights I’ve been privileged to spend in a theater, and when Richard Gaddes, who runs the Santa Fe Opera, asked Paul and me whether we thought Jonathan would be a suitable choice to direct The Letter, I nearly fell out of my chair.

(First of two parts)

TT: Almanac

“I think New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had.”

D.H. Lawrence, Phoenix

TT: Charming to a fault

In this week’s Wall Street Journal drama column I report from San Diego on the Old Globe‘s productions of The Pleasure of His Company and The Merry Wives of Windsor. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Theatrical manners have changed greatly in the half century since “The Pleasure of His Company” opened on Broadway. Nowadays it’s an insult to call a play “well-made,” but back then you could still get away with setting a neatly crafted boulevard comedy in the drawing room of a home whose owners employed a butler. Not only did “The Pleasure of His Company” run for 474 performances, but it was later turned into a Hollywood movie that did just as well at the box office. Today, though, well-made comedies are as dead as drawing rooms, and the Old Globe’s revival of “The Pleasure of His Company” is the first time that the play has been on stage anywhere since the original production closed in 1959.

Theatrical manners have changed greatly in the half century since “The Pleasure of His Company” opened on Broadway. Nowadays it’s an insult to call a play “well-made,” but back then you could still get away with setting a neatly crafted boulevard comedy in the drawing room of a home whose owners employed a butler. Not only did “The Pleasure of His Company” run for 474 performances, but it was later turned into a Hollywood movie that did just as well at the box office. Today, though, well-made comedies are as dead as drawing rooms, and the Old Globe’s revival of “The Pleasure of His Company” is the first time that the play has been on stage anywhere since the original production closed in 1959.

To what do we attribute this act of dramatic archaeology? The credit goes to Darko Tresnjak, the Old Globe’s resident artistic director, who has a taste for American stage comedies of the ’50s that you wouldn’t expect from a director born in Yugoslavia. “I find that underneath the glossy surfaces, the subtext [of these plays] is actually quite subversive,” he told James Hebert of the San Diego Union-Tribune earlier this month. Last year Mr. Tresnjak revived John van Druten’s “Bell, Book and Candle,” a quintessential example of the genre. Alas, I didn’t see that production, but if was half as stylish as this one, it must have been terrific….

Biddeford “Pogo” Poole (Patrick Page), the star of “The Pleasure of His Company,” is an ascot-wearing socialite-sportsman who walked out on Katharine (Ellen Karas), his ex-wife, and Jessica (Erin Chambers), his only daughter, to become (in Katharine’s exasperated phrase) a “globetrotting heel.” Years later he shows up on Katharine’s doorstep just in time for Jessica’s wedding, determined to charm his way into Jessica’s heart–and, if possible, Katharine’s bed. That Katharine has married again, this time to a rich, dull San Francisco businessman (Jim Abele), means nothing to Pogo, who uses his charm as an offensive weapon and is in the habit of having his own way, no matter what it costs or whom it hurts.

The part of Pogo was created on Broadway by Cyril Ritchard and played on screen by Fred Astaire, which will give you a pretty good idea of what it takes to make “The Pleasure of His Company” fly. (This is the sort of play in which lines like “I dug out some of the ancestral bourbon” and “Morality is merely low blood pressure” are tossed off between drinks.) The good news is that Mr. Tresnjak and the Old Globe have got every bit of what it takes. Not only does Mr. Page waltz through his part with the utmost suppleness and urbanity, but his supporting cast keeps him all the way up on his toes…

Across the courtyard in its attractive outdoor pavilion, the Old Globe is performing “The Merry Wives of Windsor” as part of a three-play Shakespeare festival that also includes “All’s Well That Ends Well” and “Romeo and Juliet.” Paul Mullins has staged “Merry Wives” in the manner of a Hollywood Western, turning Falstaff (Eric Hoffmann) into a Yosemite Sam-type blowhard equipped with a pair of six-shooters and a 20-gallon hat. This isn’t the first time I’ve seen a Shakespeare comedy transplanted to the Wild West–the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival did “As You Like It” in much the same way last season–and some of the actors, Mr. Hoffmann in particular, skate casually atop Mr. Mullins’ directorial conceit instead of breaking through the ice and plunging into deeper comic waters. Still, there’s plenty of uncomplicated pleasure to be found in this thoroughly agreeable production…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.