“How often have I lain beneath rain on a strange roof, thinking of home.”

William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying

OGIC: Whole cloth

There are Booker Prize winners and there are Booker Prize winners. I still vaguely rue the day that I read online about the 2003 prize going to D. B. C. Pierre’s Vernon God Little and stopped at the bookstore on the way home from work to impulsively buy it–in hardcover, no less. A few pages were enough to relegate it to the sell pile.

What a different world is the 2009 winner, Wolf Hall. Hilary Mantel’s thrilling novel of the Tudor court has been praised to the skies everywhere, so it’s not news that I’m spellbound near the halfway point. Yet the novel defies being rushed through, so I’ve been pacing myself, even starting and finishing other novels along the way (specifically, Zoë Heller’s The Believers and lately Notes on a Scandal, about which more another time). I pick up Wolf Hall when I’m feeling focused, receptive, and equal to its plenitude.

Like a Renaissance court painter, Mantel saves some of her best effects for depicting cloth–its color, texture, even the way it smells. In this middle-of-the-night scene, she describes King Henry VIII’s robe:

Henry slowly smiles. From the dream, from the night, from the night of shrouded terrors, from maggots and worms, he seems to uncurl, and stretch himself. He stands up. His face shines. The fire stripes his robe with light, and in its deep folds flicker ocher and fawn, colors of earth, of clay.

The fabric is fine, but still the stuff of Henry’s nightmares. Later in the same scene, the book’s protagonist, Thomas Cromwell, is leaving the king. He thinks of his late friend and patron Cardinal Wolsey, exiled by Henry earlier in the novel and eventually arrested, and the fate of the cardinal’s vestments. The memory speaks to him of air, not earth like Henry’s garment.

He thinks back to the day York Place was wrecked. He and George Cavendish stood by as the chests were opened and the cardinal’s vestments taken out. The copes were sewn in gold and silver thread, with patterns of golden stars, with birds, fishes, harts, lions, angels, flowers and Catherine wheels. When they were repacked and nailed into their traveling chests, the king’s men delved into the boxes that held the albs and cottas, each folded, by an expert touch, into fine pleats. Passed hand to hand, weightless as resting angels, they glowed softly in the light; loose one, a man said, let us see the quality of it. Fingers tugged at the linen bands; here, let me, George Cavendish said. Freed, the cloth drifted against the air, dazzling white, fine as a moth’s wing. When the lids of the vestments chests were raised there was the smell of cedar and spices, somber, distant, desert-dry. But the floating angels had been packed away in lavender; London rain washed against the glass, and the scent of summer flooded the dim afternoon.

When they were first seized, early in the novel, the garments didn’t seem so evanescent–they had a substance, structure, and authority that have fled in Cromwell’s memory of them.

They bring out the cardinal’s vestments, his copes. Stiff with embroidery, strewn with pearls, encrusted with gemstones, they seem to stand by themselves. The raiders knock down each one as if they are knocking down Thomas Becket. They itemize it, and having reduced it to its knees and broken its spine, they toss it into their traveling crates. Cavendish flinches: “For God’s sake, gentlemen, line those chests with a double thickness of cambric. Would you shred the fine work that has taken nuns a lifetime?”

Tapestries, as distinct from paintings, receive a similar emphasis in the novel. More about that next week.

TT: Where in the world are Terry and Mrs. T? (1)

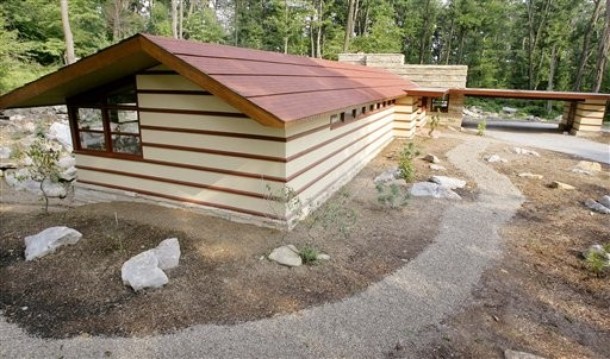

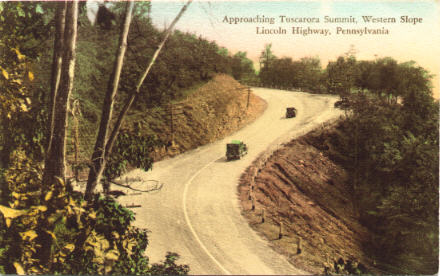

Right here:

TT: Almanac

“In the theater there are 1,500 cameras rolling at the same time–in the cinema there is only one.”

Orson Welles, interview, Cahiers du Cinéma in English, No. 5, 1966

TT: Yoicks and away

It occurred to me earlier this year that I couldn’t remember the last time I took a full-fledged two-week vacation, by which I meant two weeks spent away from home during which I (A) saw no shows and (B) wrote no pieces. When I shared this piece of information with Mrs. T, she promptly informed me that I’d better change my ways if I wanted to remain happily married. I know marching orders when I hear them, so I planned and booked a spring holiday and gave my editors at The Wall Street Journal several months’ worth of fair warning. Given the fact that the past year has seen, among countless other things, the opening of The Letter and the publication of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, I figured I’d earned some time off.

It is, of course, proverbial that the surest way to hear God laugh is to make a plan. Three Sundays ago I took Mrs. T to an emergency room in Chicago at two in the morning. Two sets of doctors, the first in Chicago and the second in Connecticut, thereupon spent the following two weeks trying to figure out exactly what was wrong with her (gallstones) and what to do about it (nothing invasive, thank God). On Tuesday she was discharged from the University of Connecticut Health Center, and yesterday we hit the road.

You will note that I haven’t said where we went, where we are now, or where we’re going next. Nor will I. The plug is well and truly pulled. I wrote and filed this week’s Wall Street Journal columns in advance of our departure, but I’m taking next week off from the paper, the first time I’ve done so since I fell ill five years ago and the second time since I became the Journal‘s drama critic seven years ago. Like I said, this is a vacation, really and truly. We are, for all intents and purposes, incommunicado: I won’t be checking my e-mail or voicemail other than sporadically, and I’m not going to write anything at all.

You will note that I haven’t said where we went, where we are now, or where we’re going next. Nor will I. The plug is well and truly pulled. I wrote and filed this week’s Wall Street Journal columns in advance of our departure, but I’m taking next week off from the paper, the first time I’ve done so since I fell ill five years ago and the second time since I became the Journal‘s drama critic seven years ago. Like I said, this is a vacation, really and truly. We are, for all intents and purposes, incommunicado: I won’t be checking my e-mail or voicemail other than sporadically, and I’m not going to write anything at all.

I’ve uploaded the usual almanac entries, weekly videos, and theater-related postings for the next two weeks, so you’ll see my ghostly presence during our absence. It’s just possible–barely–that I might tweet once or twice about the joys of taking it easy. Otherwise, though, I will have nothing to say on any subject whatsoever, here or anywhere else, until June 7.

If you happen to see me between now and then, kindly keep it to yourself.

TT: Almanac

“So large a part of human life passes in a state contrary to our natural desires, that one of the principal topics of moral instruction is the art of bearing natural calamities. And such is the certainty of evil, that it is the duty of every man to furnish his mind with those principles that may enable him to act under it with decency and propriety.”

Samuel Johnson, The Rambler, July 7, 1750 (courtesy of Anecdotal Evidence)

TT: The right stuff

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I weigh in on the New York premiere of Polly Stenham’s That Face, and I also report on the opening of another Chicago show, David Cromer’s staging of A Streetcar Named Desire. Both reviews are flat-out raves. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“That Face” is a commanding piece of work that never puts a foot wrong. I watched it with the sense that I was present at the debut of an artist who might someday have even better things in her.

Outside of her age, Ms. Stenham has nothing in common with Ms. Delaney. She is a child of privilege, the daughter of a twice-divorced businessman who attended Eton and Cambridge, and “That Face,” not at all surprisingly, is a tale of a grossly dysfunctional upper-middle-class family whose two children are choking on their own rage. I can’t think of a less interesting subject on paper–nothing is more tiresome than the whiny angst of well-off adolescents–but Ms. Stenham has somehow contrived to portray the over-familiar plight of Henry and Mia (Christopher Abbott and Cristin Milioti) with a freshness and force that took me aback.

Part of this, I’m sure, is due to the galvanic performances of Ms. Milioti, who first caught my eye in the Irish Repertory Theatre’s 2007 revival of “The Devil’s Disciple,” and the unfailingly excellent Laila Robins, who plays a drunken mother whose attachment to her son is too close for comfort. I’m just as sure that Sarah Benson, whose staging is shriekingly taut, has made the most of “That Face.”

Yet the play is deserving of its production–and in a way that is itself unusual enough to be worthy of note, since nobody says anything eloquent or even especially memorable in “That Face.” Instead of giving her principal characters high-flown speeches to speak, Ms. Stenham has put them at the center of a near-pure drama of situation and event, one in which the blame for their collective plight is distributed with a fair-mindedness that is rare in a very young writer….

David Cromer, the foremost stage director of his generation, has outdone himself with Writers’ Theatre’s revelatory new production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire.” You’d think that all there is to say about so popular a play would have been said long ago, but it is Mr. Cromer’s special gift to make old plays seem new without rendering them unrecognizable. His “Streetcar,” like the productions of “Our Town,” “The Glass Menagerie” and “Picnic” that came before it, strips the accumulated layers of convention and preconception off the surface of a classic and brings the viewer face to face with the play itself.

David Cromer, the foremost stage director of his generation, has outdone himself with Writers’ Theatre’s revelatory new production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire.” You’d think that all there is to say about so popular a play would have been said long ago, but it is Mr. Cromer’s special gift to make old plays seem new without rendering them unrecognizable. His “Streetcar,” like the productions of “Our Town,” “The Glass Menagerie” and “Picnic” that came before it, strips the accumulated layers of convention and preconception off the surface of a classic and brings the viewer face to face with the play itself.

Mr. Cromer and his set designer, Collette Pollard, have reconfigured Writers Theatre’s 108-seat performance space as a theater in the round and placed the two-room railroad flat of Stanley and Stella Kowalski (Matt Hawkins and Stacy Stoltz) in the center of the house, putting the members of audience as close to the action as it is possible to get. (I was seated eight feet from the Kowalskis’ bed.) The intimacy of this setup makes you feel as though you’re eavesdropping on “Streetcar” rather than merely watching it. It also makes it possible for the members of Mr. Cromer’s ensemble cast to underplay a show that is almost always overplayed….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“It was with my special concurrence, and indeed at my suggestion, that he went on with his law studies with undiminished zeal, as there is nothing so repugnant to me as a musician who is that alone, without any higher general culture.”

Richard Wagner, letter to Franziska von Bülow, Sept. 19, 1850