Dawn Powell and I go back a long way. I wrote about her in the New York Times Book Review in 1995, asking the same question that everybody asks: why isn’t so deliciously witty a writer more popular? Answer, alas, came there none:

Dawn Powell and I go back a long way. I wrote about her in the New York Times Book Review in 1995, asking the same question that everybody asks: why isn’t so deliciously witty a writer more popular? Answer, alas, came there none:

Every decade or so, somebody writes an essay about Dawn Powell, and a few hundred more people discover her work, and are grateful. And that’s it. Few American novelists have been so lavishly praised by so many high-powered critics to so little effect. Diana Trilling, writing in 1942, called Powell “our best answer to the familiar question, ‘Who really says the funny things for which Dorothy Parker gets credit?’”; Edmund Wilson, writing in 1962, judged her to be “quite on a level with…Anthony Powell, Evelyn Waugh and Muriel Spark”; Gore Vidal, writing in 1987, said she “should have been as widely read as, say, Hemingway or the early Fitzgerald.” No such luck. Dawn Powell remains today what she was a half-century ago: a fine and important writer adored by a handful of lucky readers in the know and ignored by everybody else.

Since then Powell has become a bit better known, thanks in small part to my review and in large part to Tim Page’s masterly 1998 biography. More recently her best novels were reprinted by the Library of America, thus ensuring that they will never again sink into the slough of unavailability that swallowed up her modest reputation for years after her death in 1965.

Now Tim has sent me a link to an astonishing Powell-related curiosity, an episode of a 1939 radio show on which she appeared. Except for an interview about the Group Theatre that was taped shortly before her death in 1965, it is the only surviving recording of Powell’s voice, and it’s interesting for all sorts of other reasons as well.

Author, Author was a prime-time literary quiz hosted by S.J. Perelman, one of The New Yorker’s resident “humorists,” as comic essayists used to be known in this country. It aired over the now-defunct Mutual Broadcasting System from April of 1939 to February of 1940. According to the announcer, “Listeners submit plot ideas with unexpected endings…Our authors are challenged to make up stories explaining those unexpected endings, and towards the end of the program, they act out a problem for our listening audience to solve.”

In addition to Perelman, Author, Author had two regular panelists, Heywood Broun and John Chapman, both of whom were fairly famous in the Thirties but are now as completely forgotten as Perelman himself is well on the way to becoming. Also present each week were a pair of guests, and on the night of October 9, 1939, they were none other than Dawn Powell and James Thurber.

Not at all surprisingly, Powell and Thurber were acquainted, as were most of the writers who lived in Manhattan in the Thirties (or so it seems, anyway). Both of them were emigrant urbanites born in Ohio toward the end of the nineteenth century, eventually moving east to set up shop as…well, humorists. Indeed, they had recently shared space in the August 26 issue of The New Yorker, she with a short story called “The Comeback” and he with a “Fable for Our Time.” Also present in the same issue was H.L. Mencken, who contributed “Memorials of Gormandizing,” which would later find its way into Happy Days.

The program on which they appeared was clever enough, though not nearly as much so as it tried to be. It was, in fact, a too-obvious knockoff of Information Please, the smartest panel show ever to run on network radio in its golden age. It didn’t help that Perelman appears to have written his own elaborately polysyllabic script. (His style of humor was meant to be read, not spoken aloud.) Time dismissed the end product as “impaired by talkiness and the occasional complete blankness of literary minds,” which strikes me as just about right.

The program on which they appeared was clever enough, though not nearly as much so as it tried to be. It was, in fact, a too-obvious knockoff of Information Please, the smartest panel show ever to run on network radio in its golden age. It didn’t help that Perelman appears to have written his own elaborately polysyllabic script. (His style of humor was meant to be read, not spoken aloud.) Time dismissed the end product as “impaired by talkiness and the occasional complete blankness of literary minds,” which strikes me as just about right.

What’s interesting about the broadcast is, for openers, the mere fact of its existence. In 1939 and for many years afterward, it was possible to put a prime-time panel show on the air that featured guests like Dawn Powell and James Thurber. Try to imagine the same thing happening today and you’ll keel over laughing.

Even more interesting, though, is the precious opportunity that this crackly-sounding aircheck provides to hear the speaking voices of two distinguished American writers. Thurber sounds very much like the Ohio expatriate he was, plain-spoken and flat-voweled. Powell, by contrast, has a medium-high voice that is at once twittery and slightly hesitant—rather like a clever little girl who says cynical things so sweetly that it takes a moment or two for you to register them and be shocked.

Even more interesting, though, is the precious opportunity that this crackly-sounding aircheck provides to hear the speaking voices of two distinguished American writers. Thurber sounds very much like the Ohio expatriate he was, plain-spoken and flat-voweled. Powell, by contrast, has a medium-high voice that is at once twittery and slightly hesitant—rather like a clever little girl who says cynical things so sweetly that it takes a moment or two for you to register them and be shocked.

While I can’t imagine going out of my way to seek out any other episodes of Author, Author, I’m very pleased to have listened to this one. As I wrote in a 2008 column, you always learn something worthwhile from the recorded voices of famous writers of the past:

Sometimes they inadvertently tell us things about themselves that we suspected but never knew for sure. Hearing Raymond Chandler’s mousy voice left me certain that he created the stalwart yet sensitive Marlowe as an act of wish fulfillment, allowing him to “do” on paper what he would never have dared do in real life. Other recordings deepen our understanding of already vivid literary personalities. H.L. Mencken was interviewed for the Library of Congress in 1948, and the gravelly speaking voice preserved in a surviving recording of that conversation is as homely as the man himself, the phrases coming in irregular, emphatic spurts, with every syllable bearing the heavily accented stamp of “Bawl-mer” (as native Baltimoreans, Mencken included, pronounce the name of their home town).

That’s why I’m delighted to add Powell and Thurber to my mental audio collection. I expect that you will be, too.

* * *

To listen to the October 9, 1939 episode of Author, Author, go here.

An interview with H.L. Mencken, recorded for the Library of Congress in 1948:

Both, I guess, since we didn’t go back in March, nor did we subsequently seek out dance of any kind (not counting Broadway, which is forever with us). But the seed was planted, and after I read Jacques d’Amboise’s

Both, I guess, since we didn’t go back in March, nor did we subsequently seek out dance of any kind (not counting Broadway, which is forever with us). But the seed was planted, and after I read Jacques d’Amboise’s  The performance that I saw fifteen years ago featured Kyra Nichols, the Balanchine dancer who meant the most to me in my balletgoing days. I

The performance that I saw fifteen years ago featured Kyra Nichols, the Balanchine dancer who meant the most to me in my balletgoing days. I  Then I walked past a poster announcing that we were about to see “Jennie Somogyi’s Farewell Performance.” Somogyi, who joined NYCB in 1994, is a member of the last generation of up-and-coming dancers whose careers I once

Then I walked past a poster announcing that we were about to see “Jennie Somogyi’s Farewell Performance.” Somogyi, who joined NYCB in 1994, is a member of the last generation of up-and-coming dancers whose careers I once  I won’t pretend to judge the merits of the performance of Liebeslieder Walzer that we saw yesterday afternoon. Not only is my critic’s eye out of practice, but it was also dimmed by tears. Instead I’ll cite two experts, one of whom, the late

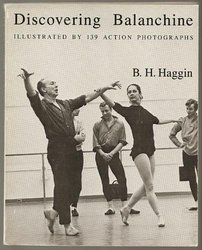

I won’t pretend to judge the merits of the performance of Liebeslieder Walzer that we saw yesterday afternoon. Not only is my critic’s eye out of practice, but it was also dimmed by tears. Instead I’ll cite two experts, one of whom, the late  Part of what Haggin was getting at is that whatever else they were, Balanchine’s dances were theater above all. I can’t imagine that observation being more to the point, then or now, than in the case of Liebeslieder Walzer, which to my mind is one of the most extraordinary works of lyric theater created in the twentieth century, a masterpiece that is all the more miraculous because it is a plotless ballet whose poetic effect derives entirely from the fusion of music, movement, and décor. Richard Wagner couldn’t have conceived of a more radically unified work of art.

Part of what Haggin was getting at is that whatever else they were, Balanchine’s dances were theater above all. I can’t imagine that observation being more to the point, then or now, than in the case of Liebeslieder Walzer, which to my mind is one of the most extraordinary works of lyric theater created in the twentieth century, a masterpiece that is all the more miraculous because it is a plotless ballet whose poetic effect derives entirely from the fusion of music, movement, and décor. Richard Wagner couldn’t have conceived of a more radically unified work of art.

If you don’t know “Fool for Love,” it’s a brutally compact play (four actors, no intermission, 75 minutes) set in a cheap motel room on the edge of the Mojave Desert. The central characters are May and Eddie (Ms. Arianda and Sam Rockwell), a couple who can’t decide whether to have sex or kill each other. I exaggerate, but only slightly, and while their indecision has its comic side—one that Mr. Aukin has wisely emphasized in order to leaven the dramatic loaf—the obsession that has flung them together is no joke….

If you don’t know “Fool for Love,” it’s a brutally compact play (four actors, no intermission, 75 minutes) set in a cheap motel room on the edge of the Mojave Desert. The central characters are May and Eddie (Ms. Arianda and Sam Rockwell), a couple who can’t decide whether to have sex or kill each other. I exaggerate, but only slightly, and while their indecision has its comic side—one that Mr. Aukin has wisely emphasized in order to leaven the dramatic loaf—the obsession that has flung them together is no joke…. “The Diary of Anne Frank” hasn’t been seen on Broadway since 1998, but it remains a perennial staple of regional theaters, with good reason. Adapted for the stage in 1955 by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, it’s a slightly creaky but nonetheless dramaturgically sound theatrical version of the real-life tale of a teenage Jewish girl from Amsterdam who hid from the Nazis with her family, recording her experiences in a diary that was left behind when the Franks were captured by the SS in 1944. Though Anne later died in Bergen-Belsen, her story lives on, and the Pittsburgh Public Theater is retelling it with absorbing skill in a production that is all the more moving for being played out against the black backdrop of Europe’s recrudescent anti-Semitism….

“The Diary of Anne Frank” hasn’t been seen on Broadway since 1998, but it remains a perennial staple of regional theaters, with good reason. Adapted for the stage in 1955 by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, it’s a slightly creaky but nonetheless dramaturgically sound theatrical version of the real-life tale of a teenage Jewish girl from Amsterdam who hid from the Nazis with her family, recording her experiences in a diary that was left behind when the Franks were captured by the SS in 1944. Though Anne later died in Bergen-Belsen, her story lives on, and the Pittsburgh Public Theater is retelling it with absorbing skill in a production that is all the more moving for being played out against the black backdrop of Europe’s recrudescent anti-Semitism…. I got in touch with Harvard a few months ago and suggested that they post the broadcast online, and now they’re done so. Go

I got in touch with Harvard a few months ago and suggested that they post the broadcast online, and now they’re done so. Go