Kenneth Tynan interviews Laurence Olivier in 1966:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“Honors go to those who want them.”

Michael Oakeshott (quoted in Paul Franco, Michael Oakeshott: An Introduction, courtesy of Tim Hulsey)

TT: Almanac

“What we, or at any rate what I, refer to confidently as memory–meaning a moment, a scene, a fact that has been subjected to a fixative and thereby rescued from oblivion–is really a form of storytelling that goes on continually in the mind and often changes with the telling. Too many conflicting emotional interests are involved for life ever to be wholly acceptable, and possibly it is the work of the storyteller to rearrange things so that they conform to this end. In any case, in talking about the past we lie with every breath we draw.”

William Maxwell, So Long, See You Tomorrow

TT: At full tilt

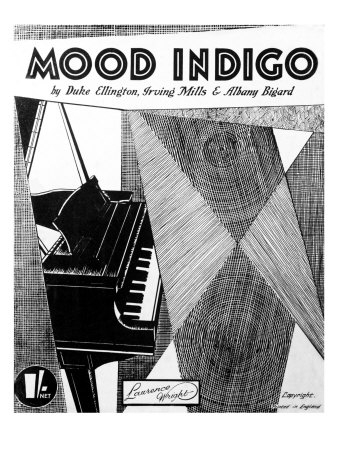

I went at Mood Indigo: A Life of Duke Ellington with hammer and tongs last week, and by the time I was done, I’d written the first 16,000 words of the fifth chapter, which will take Ellington from 1929 to 1933.

I went at Mood Indigo: A Life of Duke Ellington with hammer and tongs last week, and by the time I was done, I’d written the first 16,000 words of the fifth chapter, which will take Ellington from 1929 to 1933.

Appropriately enough, one of the things that I wrote was a discussion of “Mood Indigo” itself. I especially like this paragraph:

Ellington is said to have thought “Old Man Blues” to be his best composition yet. It’s easy to see why he was so pleased with it, but “Mood Indigo,” recorded two months later by a seven-piece combo drawn from the band, is even more inspired, and unlike “Old Man Blues,” which was rarely heard in later years, it became a permanent and beloved part of the band’s working repertoire. A nocturne whose “exquisitely tired and four-in-the-morning” atmosphere (in Constant Lambert’s phrase) he would evoke time and again, “Mood Indigo” opens with a three-part chorale intoned by muted trumpet, muted trombone, and low-register clarinet, the same combination that André Previn had in mind when he marveled at how “Duke merely lifts his finger, three horns make a sound, and I don’t know what it is.” Then Barney Bigard steps out from the ensemble to play the tune, a rich and shapely melody backed by the tick-tock strokes of Freddy Guy’s banjo and the smooth, steady walk of the rest of the rhythm section. Arthur Whetsel plays a delicate solo and Ellington flutters gracefully through a lacy four-bar piano interlude, after which the chorale is repeated as the record spins to a close. Two months later the full band re-recorded “Mood Indigo,” but Ellington knew better than to tamper with the scoring of the introductory chorale. It is as simple–and unforgettable–as a proverb.

I’m feeling good about the book again. Can you tell?

* * *

A Snader Telescriptions film of “Mood Indigo” performed by the Ellington orchestra in 1951. The clarinet solo is by Jimmy Hamilton. The arrangement, by Billy Strayhorn, is significantly different from the one described above:

Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier “play” “Mood Indigo” in the 1961 film Paris Blues. Newman’s trombone was dubbed by Murray McEachern. The onscreen pianist is Aaron Bridgers, Billy Strayhorn’s first lover:

TT: Just because

Elaine May and Mike Nichols appear in a commercial for General Electric:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“There is no great harm in the theorist who makes up a new theory to fit a new event. But the theorist who starts with a false theory and then sees everything as making it come true is the most dangerous enemy of human reason.”

G.K. Chesterton, The Flying Inn

TT: See me, hear me (cont’d)

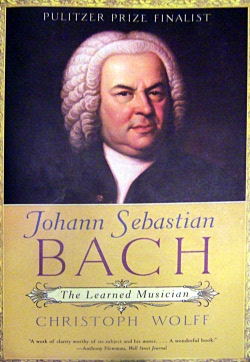

If you’re going to be in or near Winter Park, Florida, on Sunday afternoon, I’ll be making a public appearance at Rollins College under the auspices of Winter Park’s Bach Festival.

If you’re going to be in or near Winter Park, Florida, on Sunday afternoon, I’ll be making a public appearance at Rollins College under the auspices of Winter Park’s Bach Festival.

Quoth the press release:

Join us for a lively discussion about the work and legacy of J.S. Bach with guest scholar Dr. Christoph Wolff, conductor Dr. John Sinclair, and Wall Street Journal arts writer Terry Teachout.

I’d say that’s straightforward enough!

For those not in the know, Dr. Wolff is one of the world’s great Bach scholars, Dr. Sinclair is the chairman of the music department at Rollins and the Bach Festival’s head honcho, and I’m…well, me. I’ll be moderating the chat, and I promise to keep things both lively and fully accessible to the interested layman.

The program starts at one p.m. in the Galloway Room of the Cornell Campus Center. Admission is free, but you have to reserve a seat in advance by calling 407-646-2182. You can also order a box lunch (I’m having one).

For more information, go here.

TT: Waiting for Mandela

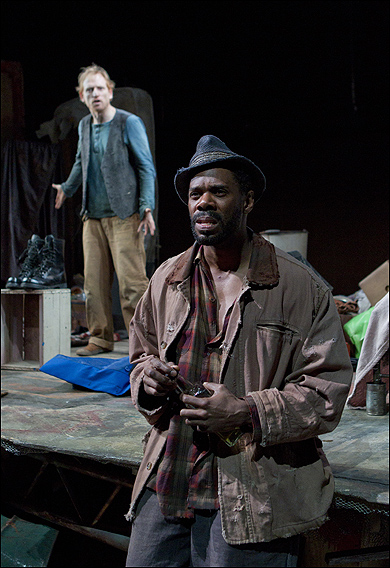

Today’s Wall Street Journal drama column is devoted in its entirety to a review of Signature Theatre’s off-Broadway revival of Blood Knot. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Audiences in New York haven’t been able to see much of the work of Athol Fugard, South Africa’s greatest playwright, in recent years, but his stock is now taking a sharp leap upward. In addition to the Roundabout Theatre Company’s current Broadway revival of “The Road to Mecca,” Signature Theatre is mounting three Fugard productions this season, the first of which, “Blood Knot,” has been directed by the author himself. That alone is reason to go, since “Blood Knot,” the 1961 two-man play that introduced Mr. Fugard to the world’s stages, is a modern classic, a play that moves with stealthy sureness from a quiet, almost nonchalant start to an overwhelming conclusion. To see what Mr. Fugard has done with it would be a must even if his staging were less effective–and he has done exactly right by “Blood Knot.” If you don’t find this revival enthralling, you’re not thrillable.

Mr. Fugard’s two characters, Zach (Colman Domingo) and Morris (Scott Shepherd), live together in a pathetic-looking one-room shack built out of cardboard boxes and corrugated iron. Zach is dark-skinned, Morris light-skinned, and if you were to see them walking down the street, you’d never guess that they were related, much less that they are half-brothers. Cut off from the world by poverty, they spend their free time playing out child-like fantasies together. It is this penchant for fantasy that inspires Morris to find a female pen-pal for his illiterate brother, who longs in vain for a real live girl (Zach dictates his letters to Morris, who polishes up his grammar, then reads the replies to him). What starts out as a gentle working-class variation on “The Shop Around the Corner” then turns deadly serious when Ethel, Zach’s correspondent, suggests that they meet, enclosing a snapshot which reveals that she is white.

Mr. Fugard’s two characters, Zach (Colman Domingo) and Morris (Scott Shepherd), live together in a pathetic-looking one-room shack built out of cardboard boxes and corrugated iron. Zach is dark-skinned, Morris light-skinned, and if you were to see them walking down the street, you’d never guess that they were related, much less that they are half-brothers. Cut off from the world by poverty, they spend their free time playing out child-like fantasies together. It is this penchant for fantasy that inspires Morris to find a female pen-pal for his illiterate brother, who longs in vain for a real live girl (Zach dictates his letters to Morris, who polishes up his grammar, then reads the replies to him). What starts out as a gentle working-class variation on “The Shop Around the Corner” then turns deadly serious when Ethel, Zach’s correspondent, suggests that they meet, enclosing a snapshot which reveals that she is white.

Mr. Fugard could have developed this promising scenario in any number of conventionally “effective” ways. Instead, taking Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” as his point of departure, he has sketched the plight of his characters plight in a way that is partly comic and partly surreal….

The verdict of posterity has yet to be handed down on the rest of Mr. Fugard’s oeuvre, but judging by this revival, I’d say that “Blood Knot” will remain fresh for some time to come. The reason for its freshness is that Mr. Fugard, though he leaves you in no doubt of the play’s political implications, embeds them in poetic symbolism rather than stooping to the kind of explicit sermonizing that kills so many political plays stone dead.

Mr. Fugard has staged “Blood Knot” with a similarly light touch, emphasizing the play’s slapstick physicality and allowing its sweetness free rein. Messrs. Domingo and and Shepherd are no less alive to the comedy of “Blood Knot,” so much so that they reminded me at times of Laurel and Hardy….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.