“Nothing so concentrates the mind as having to write. In my own case, I frequently do not know what I really think about a writer, a general subject, an event, a person, until I set out my thoughts on the page.”

“Nothing so concentrates the mind as having to write. In my own case, I frequently do not know what I really think about a writer, a general subject, an event, a person, until I set out my thoughts on the page.”

Joseph Epstein, Partial Payments: Essays on Writers and Their Lives (courtesy of Patrick Kurp)

Now that Mrs. T is

Now that Mrs. T is  Not wanting to risk missing any part of the show, I landed inconveniently early, picked up a rental car, and drove to Forest Park and the

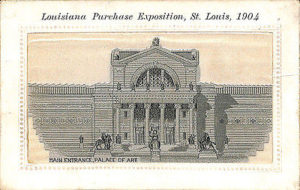

Not wanting to risk missing any part of the show, I landed inconveniently early, picked up a rental car, and drove to Forest Park and the  I visited the St. Louis Art Museum for the first time well into adulthood, my parents not being museumgoers. Too bad for me: it is, I suspect, a near-ideal first museum for those who know little of the visual arts, aspiring to encyclopedic status without being too big to swamp the casual visitor. (It houses 34,000 works of art, one-tenth as many as are owned by the Art Institute of Chicago.) Most of the show-stoppers, which include first-class pieces by Holbein, Titian, Monet, Van Gogh, and Matisse, are on more or less continuous display, and you can see them all without becoming art-drunk along the way. Like many regional museums, the museum also makes a point of hanging lesser-known canvases by such unfashionable American masters as Stuart Davis, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and John Twachtman, which are sprinkled throughout the galleries with gratifying frequency.

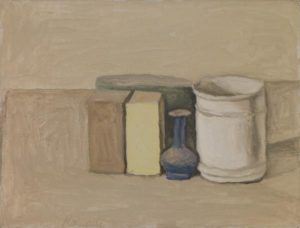

I visited the St. Louis Art Museum for the first time well into adulthood, my parents not being museumgoers. Too bad for me: it is, I suspect, a near-ideal first museum for those who know little of the visual arts, aspiring to encyclopedic status without being too big to swamp the casual visitor. (It houses 34,000 works of art, one-tenth as many as are owned by the Art Institute of Chicago.) Most of the show-stoppers, which include first-class pieces by Holbein, Titian, Monet, Van Gogh, and Matisse, are on more or less continuous display, and you can see them all without becoming art-drunk along the way. Like many regional museums, the museum also makes a point of hanging lesser-known canvases by such unfashionable American masters as Stuart Davis, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and John Twachtman, which are sprinkled throughout the galleries with gratifying frequency. I last visited the St. Louis Art Museum in 2009, so I knew I’d want to spend a couple of hours there, and I also knew which piece I’d see first: Giorgio Morandi’s

I last visited the St. Louis Art Museum in 2009, so I knew I’d want to spend a couple of hours there, and I also knew which piece I’d see first: Giorgio Morandi’s  Not having eaten since I’d grabbed an overpriced breakfast sandwich at LaGuardia, I drove straight from the museum to

Not having eaten since I’d grabbed an overpriced breakfast sandwich at LaGuardia, I drove straight from the museum to  For all these reasons, I would never claim to say with any pretense of objectivity how well the Muny performed Jerome Robbins’ Broadway. Closely though I watched the performance, I did so through a scrim of tears, and my head was full of deep-etched memories (though I wasn’t quite so carried away as to fail to notice the mid-show protest that I

For all these reasons, I would never claim to say with any pretense of objectivity how well the Muny performed Jerome Robbins’ Broadway. Closely though I watched the performance, I did so through a scrim of tears, and my head was full of deep-etched memories (though I wasn’t quite so carried away as to fail to notice the mid-show protest that I  I attended the first of those reunions, after which I

I attended the first of those reunions, after which I  I still feel the same way, and I can’t put it any better now than I did then. Of all the myriad blessings whose sum is my life, none was greater than that of being born into an “ordinary” family from a small town located squarely—in every sense of the word—in the middle of America. All that I am, all that I’ve done since I left home to make my way in the world, is rooted in that soil.

I still feel the same way, and I can’t put it any better now than I did then. Of all the myriad blessings whose sum is my life, none was greater than that of being born into an “ordinary” family from a small town located squarely—in every sense of the word—in the middle of America. All that I am, all that I’ve done since I left home to make my way in the world, is rooted in that soil.

Forty-nine years after his death, Miles Malleson has become the answer to a trivia question. He was one of those funny-faced comic character actors (one of his three wives claimed that he looked “exactly like a hobgoblin”) whom everyone remembers but few know by name, the English counterpart of Eugene Pallette or S.Z. Sakall. The list of distinguished films in which he played small but striking parts includes “The Importance of Being Earnest,” “Kind Hearts and Coronets” (he was the hangman), “The Man in the White Suit,” “Peeping Tom,” and Alfred Hitchcock’s “Stage Fright” and “The 39 Steps,” and he also had a similarly noteworthy stage career, most famously as Polonius to John Gielgud’s Hamlet in 1944. In addition, though, Malleson wrote a fair number of plays, some of which were briefly successful but all of which are now forgotten. That’s where the Mint Theater Company comes in.

Forty-nine years after his death, Miles Malleson has become the answer to a trivia question. He was one of those funny-faced comic character actors (one of his three wives claimed that he looked “exactly like a hobgoblin”) whom everyone remembers but few know by name, the English counterpart of Eugene Pallette or S.Z. Sakall. The list of distinguished films in which he played small but striking parts includes “The Importance of Being Earnest,” “Kind Hearts and Coronets” (he was the hangman), “The Man in the White Suit,” “Peeping Tom,” and Alfred Hitchcock’s “Stage Fright” and “The 39 Steps,” and he also had a similarly noteworthy stage career, most famously as Polonius to John Gielgud’s Hamlet in 1944. In addition, though, Malleson wrote a fair number of plays, some of which were briefly successful but all of which are now forgotten. That’s where the Mint Theater Company comes in.  In private life, Malleson was a deadly earnest socialist, a Labour Party activist and (latterly) Communist fellow traveler whose plays were vehicles for his left-wing views. But if that sounds discouraging, fear not: In “Conflict,” Malleson embedded his world-saving politics in a soundly plotted drama whose light tone is more reminiscent of a drawing-room comedy than a Shavian play of ideas and which ends with a bases-loaded coup de théâtre. It’s as though one of John Galsworthy’s plays had been rewritten by Terence Rattigan….

In private life, Malleson was a deadly earnest socialist, a Labour Party activist and (latterly) Communist fellow traveler whose plays were vehicles for his left-wing views. But if that sounds discouraging, fear not: In “Conflict,” Malleson embedded his world-saving politics in a soundly plotted drama whose light tone is more reminiscent of a drawing-room comedy than a Shavian play of ideas and which ends with a bases-loaded coup de théâtre. It’s as though one of John Galsworthy’s plays had been rewritten by Terence Rattigan….