In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I pay tribute to the late Peter Shaffer. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The obituaries for Peter Shaffer, who died the other day at the age of 90 and for whom Broadway is dimming its lights on Thursday, were respectful but not effusive. The respect makes sense, since he wrote, among other things, “Amadeus” and “Equus,” two of the most successful plays of the postwar era. The conspicuous lack of wholehearted enthusiasm, however, also makes sense, since Mr. Shaffer, for all his success, wasn’t anybody’s favorite playwright, nor is his work frequently seen in this country nowadays….

Why has Mr. Shaffer faded from the scene? The main reason is undoubtedly that most of his best-known plays, which were written for England’s state-subsidized theaters, were large-scale works whose big casts (“Amadeus” and “Equus” both require 15 actors) put them out of reach of most American companies. At the same time, though, I get the impression that Mr. Shaffer is regarded by many drama critics as a middlebrow, a purveyor of high-minded, impeccably effective plays in which he watered down challenging subjects to make them palatable to the masses. A poor man’s Tom Stoppard, you might say.

Why has Mr. Shaffer faded from the scene? The main reason is undoubtedly that most of his best-known plays, which were written for England’s state-subsidized theaters, were large-scale works whose big casts (“Amadeus” and “Equus” both require 15 actors) put them out of reach of most American companies. At the same time, though, I get the impression that Mr. Shaffer is regarded by many drama critics as a middlebrow, a purveyor of high-minded, impeccably effective plays in which he watered down challenging subjects to make them palatable to the masses. A poor man’s Tom Stoppard, you might say.

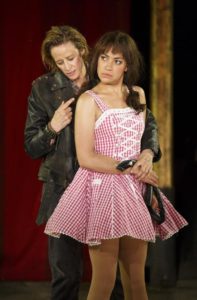

It may be that there’s something to that indictment, though it certainly fails to do justice to “Amadeus,” which has long struck me, both in its original 1979 stage version and in Miloš Forman’s justly successful 1984 screen adaptation, as an immensely potent parable of the terrible mystery of human inequality. As for “Equus,” in which Mr. Shaffer took the tale of a stableboy who blinds horses for no apparent reason and turned it into a gripping study of middle-class emotional inhibition, it’s a bit creakier, but the 2008 revival proved that it still packs a walloping theatrical punch when staged with skill and conviction.

More to the point, though, is that Mr. Shaffer’s plays, whether you like them or not, were both genuinely serious and hugely successful….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Paul Scofield in a scene from the original production of Amadeus, directed by Peter Hall and filmed at London’s National Theatre:

F. Murray Abraham in the same scene from Miloš Forman’s film version of Amadeus, adapted for the screen by Peter Shaffer:

•

•

The culprit is presumably Ms. Lloyd, who is most familiar to American audiences as the director of “The Iron Lady” and the film version of “Mamma Mia!” but is known in her native England as a stage director of distinction. Be that as it may, there isn’t much in her resumé to suggest that comedy is her forte, and little in this production to contradict that impression. While it’s full of baggy-pants slapstick, the timing of the gags is loose, unsure and short on the head-turning, split-second snap of surprise without which such antics invariably come off as noisy rather than funny.

The culprit is presumably Ms. Lloyd, who is most familiar to American audiences as the director of “The Iron Lady” and the film version of “Mamma Mia!” but is known in her native England as a stage director of distinction. Be that as it may, there isn’t much in her resumé to suggest that comedy is her forte, and little in this production to contradict that impression. While it’s full of baggy-pants slapstick, the timing of the gags is loose, unsure and short on the head-turning, split-second snap of surprise without which such antics invariably come off as noisy rather than funny.

A fast-growing number of the magazines and newspapers that I read on line are now imposing rigid limits on free articles-per-month for non-subscribers. I know why they do it, and I couldn’t sympathize more. Even so, my guess is that most Americans respond to those limits by ceasing to read the publications that impose them—and given the vast amount of other good stuff to read that’s out there on the web, I can’t help but wonder about the future of journalism, mainstream and otherwise, in a country where fewer and fewer people are willing to pay for it.

A fast-growing number of the magazines and newspapers that I read on line are now imposing rigid limits on free articles-per-month for non-subscribers. I know why they do it, and I couldn’t sympathize more. Even so, my guess is that most Americans respond to those limits by ceasing to read the publications that impose them—and given the vast amount of other good stuff to read that’s out there on the web, I can’t help but wonder about the future of journalism, mainstream and otherwise, in a country where fewer and fewer people are willing to pay for it. More and more, though, we don’t live together and we don’t listen to each other. As a result, the modest but real tolerance of the past is increasingly giving way to attempts at outright repression, or (more often, at least for now) the sniggeringly dismissive attitude exemplified by this Washington Post

More and more, though, we don’t live together and we don’t listen to each other. As a result, the modest but real tolerance of the past is increasingly giving way to attempts at outright repression, or (more often, at least for now) the sniggeringly dismissive attitude exemplified by this Washington Post  The main obstacle that stands in the way of the soft disunion of America is that Red and Blue America are not geographically disjunct, as were the North and South in the Civil War. Even in the biggest and reddest of states, there are deep-blue enclaves that have no wish to be absorbed into the whole. Perhaps they will be the West Berlins of the twenty-first century, tiny islands of dissent in vast seas of concord. But if the desire to separate is strong enough, then the problem will surely be solved one way or another. Abraham Lincoln said it: “If destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide.” And so we may, sundered by inattention.

The main obstacle that stands in the way of the soft disunion of America is that Red and Blue America are not geographically disjunct, as were the North and South in the Civil War. Even in the biggest and reddest of states, there are deep-blue enclaves that have no wish to be absorbed into the whole. Perhaps they will be the West Berlins of the twenty-first century, tiny islands of dissent in vast seas of concord. But if the desire to separate is strong enough, then the problem will surely be solved one way or another. Abraham Lincoln said it: “If destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide.” And so we may, sundered by inattention.