Can you seriously imagine a senator, or any other public figure, commiting suicide under similar circumstances today? In fact, let’s take it one step further: can you think of any secret so shameful that a contemporary public figure would rather die than face the consequences of its becoming known? I can’t….

Read the whole thing here.

It doesn’t happen all that often these days, but I found myself home alone in New York last Friday night. Mrs. T was in Connecticut. I had no show to see that evening, nor was a pressing deadline hanging over my head, so I sent out for sushi, read a novel while I ate it, watched a movie I’d seen a half-dozen times before, lit a candle and watched it burn, and enjoyed the pleasant sensation of having nothing in particular to do.

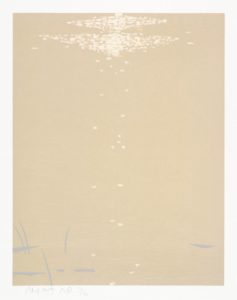

It doesn’t happen all that often these days, but I found myself home alone in New York last Friday night. Mrs. T was in Connecticut. I had no show to see that evening, nor was a pressing deadline hanging over my head, so I sent out for sushi, read a novel while I ate it, watched a movie I’d seen a half-dozen times before, lit a candle and watched it burn, and enjoyed the pleasant sensation of having nothing in particular to do. Mrs. T and I have chosen the pieces that we own with great care, and so far none of them has “gone dead on the wall,” as longtime collectors say. While we each have our particular favorites, I can honestly say that I love every work in our collection. That doesn’t mean, however, that I look at each and every piece whenever I’m home. A few of our prints, Helen Frankenthaler’s “Grey Fireworks” in particular, are so large and spectacular that they’re hard not to notice, while others, like “Northern Landscape (Bright Light),” are easy to overlook, rather like a shy child who never speaks up in class. And you know what? It doesn’t matter, not in the least.

Mrs. T and I have chosen the pieces that we own with great care, and so far none of them has “gone dead on the wall,” as longtime collectors say. While we each have our particular favorites, I can honestly say that I love every work in our collection. That doesn’t mean, however, that I look at each and every piece whenever I’m home. A few of our prints, Helen Frankenthaler’s “Grey Fireworks” in particular, are so large and spectacular that they’re hard not to notice, while others, like “Northern Landscape (Bright Light),” are easy to overlook, rather like a shy child who never speaks up in class. And you know what? It doesn’t matter, not in the least.

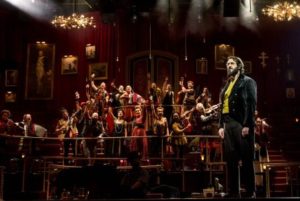

For all its explosive liveliness, Ms. Chavkin’s staging looks like a hopped-up concert version of a musical, not a bonafide Broadway show, and it serves mainly to paper over the essentially undramatic nature of “The Great Comet,” which feels less like an opera than a cantata—or, rather, a novel sung out loud. Large chunks of the unrhymed text come directly from Tolstoy’s book, and the characters spend most of their onstage time telling us what’s happening and how they feel about it instead of showing us. This impression is reinforced by Mr. Malloy’s songs, whose “tunes” are flattened-out non-melodies that exist only to carry the relentlessly wordy text and are superimposed on riffy vamps and short, oft-repeated harmonic cells. If that suggests minimalism, there’s a reason: Much of “The Great Comet” sounds quite a bit like what I imagine Philip Glass might have written had he decided to be a pop singer-songwriter, not a classical composer….

For all its explosive liveliness, Ms. Chavkin’s staging looks like a hopped-up concert version of a musical, not a bonafide Broadway show, and it serves mainly to paper over the essentially undramatic nature of “The Great Comet,” which feels less like an opera than a cantata—or, rather, a novel sung out loud. Large chunks of the unrhymed text come directly from Tolstoy’s book, and the characters spend most of their onstage time telling us what’s happening and how they feel about it instead of showing us. This impression is reinforced by Mr. Malloy’s songs, whose “tunes” are flattened-out non-melodies that exist only to carry the relentlessly wordy text and are superimposed on riffy vamps and short, oft-repeated harmonic cells. If that suggests minimalism, there’s a reason: Much of “The Great Comet” sounds quite a bit like what I imagine Philip Glass might have written had he decided to be a pop singer-songwriter, not a classical composer….