Memory is the great blessing of a happy life. I have nothing but pleasant memories of my mother’s family’s Fourth of July cookouts, which rank among the highlights of my small-town youth. Those picnics are part of the distant past now, and my parents and all but one of my mother’s siblings are dead. My brother and sister-in-law (bless them!) brought the remaining members of our family together last summer for a reunion that was joyous almost beyond belief, but nothing can quite measure up to the remembered pleasures of childhood. Fortunately, I have enough of those to last me the rest of my days.

Memory is the great blessing of a happy life. I have nothing but pleasant memories of my mother’s family’s Fourth of July cookouts, which rank among the highlights of my small-town youth. Those picnics are part of the distant past now, and my parents and all but one of my mother’s siblings are dead. My brother and sister-in-law (bless them!) brought the remaining members of our family together last summer for a reunion that was joyous almost beyond belief, but nothing can quite measure up to the remembered pleasures of childhood. Fortunately, I have enough of those to last me the rest of my days.

In 1991, a quarter of a century ago, I published a memoir in which, among many other things, I described those Fourth of July cookouts. This is part of what I wrote. I posted it in this space two years ago, and it still gives me pleasure to read. I hope you feel the same way.

* * *

We would pull into my grandmother’s driveway early in the afternoon. My parents would go inside to sit with the old people and take part in the slow, steady talk that holds a large family together. (I thought of my aunts and uncles as “the old people,” though they were no older than I am now.) I went inside to say hello, too, but I slipped away as quickly as I could, for there were better things to do on a summer day than sitting around listening to the old people talk. Sometimes I played softball with Mike, Bob, and Gary, my older cousins, in the empty lot next to Uncle Marshall’s garage. Sometimes I shinnied up the low-slung mimosa tree next to my grandmother’s house. Sometimes I walked down the road to Uncle Albert’s house or across the street to Dot and Marshall’s to gaze jealously at a new toy. Sometimes I hid out in Dot and Marshall’s living room and spent the day reading about Huckleberry Finn or Captain Ahab.

Later in the day, the older cousins would start dipping into their private stashes of small-bore fireworks suitable for daytime use. Gary favored tiny cylinders that swelled into long, wormy spirals of ash that left huge gray-and-black smears on the front porch; Bob preferred little pellets that exploded with an ear-shattering crack when thrown at the nearest rock. Mike usually had a bag full of smoke bombs, and I liked those best. You put a little cardboard sphere in the middle of a dirt road, lit the fuse, and watched it belch forth clouds of foul green smoke. I had no fireworks of my own, for my parents were certain that it would be crazy to turn me loose with them, and they were probably right. So I watched and waited and tried from time to time to talk Mike into letting me touch the glowing end of a piece of punk to the stubby fuse of one of his smoke bombs.

Later in the day, the older cousins would start dipping into their private stashes of small-bore fireworks suitable for daytime use. Gary favored tiny cylinders that swelled into long, wormy spirals of ash that left huge gray-and-black smears on the front porch; Bob preferred little pellets that exploded with an ear-shattering crack when thrown at the nearest rock. Mike usually had a bag full of smoke bombs, and I liked those best. You put a little cardboard sphere in the middle of a dirt road, lit the fuse, and watched it belch forth clouds of foul green smoke. I had no fireworks of my own, for my parents were certain that it would be crazy to turn me loose with them, and they were probably right. So I watched and waited and tried from time to time to talk Mike into letting me touch the glowing end of a piece of punk to the stubby fuse of one of his smoke bombs.

After the last firecracker was lit and tossed, I crawled into the wooden swing on the crumbling front porch of my grandmother’s house and rocked into the breeze. Once in a while I brought a book with me, for there are few things as pleasant as reading a good book while sitting in a porch swing on a breezy summer day. More often, though, I left my book in the car, especially after my spindly legs grew long enough to reach the concrete floor of the porch. Then I would sit at the very edge of the broad wooden seat, kick as hard as I could and push the swing higher and higher into the air, high enough that the soles of my sneakers scraped the ceiling and the heavy chains of the swing gave off a scary thump every time I fell back to earth. The higher I swung, the surer I was that the rusty bolts would gradually work their way out of the rotten wood of the ceiling, sending me flying through the air to a bloody but glorious death. Before long, one of the old people always came stomping out of the house and told me to cut it out before I cracked my fool head open.

In the middle of the long afternoon, the whole family gathered on the front porch to make ice cream. The older cousins took turns cranking the old wooden freezer. After half an hour of steady cranking, Uncle Albert unscrewed the lid of the freezer and scooped out rich, grainy, colder-than-cold bowls of pale yellow custard. I ate mine in silence, nursing an ice-cream headache. Then the aunts retired to the kitchen and the uncles set up charcoal grills in the front yard and build roaring fires. Dinner was served as the sun began to set. We wolfed down hot dogs, hamburgers, barbecued pork steaks, potato salad, creamed corn, hot rolls, and my mother’s spicy baked beans. Then we cleared away the dishes and ate more ice cream and sat and talked until the last light had died away and it was time to cross the dirt road to the empty lot and shoot fireworks.

The old people gave each child a silver sparkler and a skinny brown stick of punk that filled the air with an incenselike smell when lit. As we waved our sparklers, Uncle Albert placed a squat, five-barreled cardboard cylinder on the ground. Mike approached it slowly and ceremonially, punk in hand, the other cousins looking on from a safe distance. We held our breath as he cautiously touched the fuse at the bace of the cylinder with the smoldering stick of punk. Nothing happened. He touched it again. Was this one a dud? Then the fuse caught fire with a loud, rasping fizz and Mike darted away as a dozen red and green and blue fireballs shot into the air and exploded into a million golden dots of short-lived flame.

My father liked Roman candles, and I remember the first Fourth of July that he let me hold one on my own. First came the warning: “This isn’t a toy, son. You could put somebody’s eye out with it. Point it up and away and whatever you do, don’t aim it at anybody. Do you understand?” I nodded, my heart racing with excitement. Then he lit the top end and handed me the slim cardboard tube. I pointed it up and away, but I knew that it was aimed at somebody, though I told no one that I was actually a mighty warrior locked in single combat with the evil forces of darkness. I shouted every time the sizzling tube went crump and lit up the sky with gaudy bursts of lightning, each one aimed squarely at the forehead of a giant monster from outer space. I dreamed of blue fireballs for weeks.

My father liked Roman candles, and I remember the first Fourth of July that he let me hold one on my own. First came the warning: “This isn’t a toy, son. You could put somebody’s eye out with it. Point it up and away and whatever you do, don’t aim it at anybody. Do you understand?” I nodded, my heart racing with excitement. Then he lit the top end and handed me the slim cardboard tube. I pointed it up and away, but I knew that it was aimed at somebody, though I told no one that I was actually a mighty warrior locked in single combat with the evil forces of darkness. I shouted every time the sizzling tube went crump and lit up the sky with gaudy bursts of lightning, each one aimed squarely at the forehead of a giant monster from outer space. I dreamed of blue fireballs for weeks.

* * *

Dawn Upshaw, David Zinman and the Orchestra of St. Luke’s perform Samuel Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915. The text is by James Agee:

It figures, then, that first-class revivals of “Company” should be thin on the ground. I’ve reviewed only two, on Broadway in 2006 and at Pennsylvania’s Bucks County Playhouse last summer. Now there’s a third: William Brown, one of Chicago’s top directors, has given us a small-scale, contemporary-flavored “Company” (everyone uses cellphones) that is the most dramatically persuasive version I’ve seen to date. It’s the first musical to be mounted on Writers Theatre’s brand-new 250-seat main stage, and it takes full advantage of that handsome space. Indeed, the real “star” of the show is Todd Rosenthal, the set designer. Best known in New York for “August: Osage County,” he has concocted a multi-tiered performing space that shows you how the complex narrative structure of “Company” works. Everything about this production is wholly satisfying, but it’s Mr. Rosenthal’s set that makes the pieces fit together so tightly….

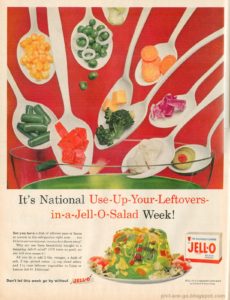

It figures, then, that first-class revivals of “Company” should be thin on the ground. I’ve reviewed only two, on Broadway in 2006 and at Pennsylvania’s Bucks County Playhouse last summer. Now there’s a third: William Brown, one of Chicago’s top directors, has given us a small-scale, contemporary-flavored “Company” (everyone uses cellphones) that is the most dramatically persuasive version I’ve seen to date. It’s the first musical to be mounted on Writers Theatre’s brand-new 250-seat main stage, and it takes full advantage of that handsome space. Indeed, the real “star” of the show is Todd Rosenthal, the set designer. Best known in New York for “August: Osage County,” he has concocted a multi-tiered performing space that shows you how the complex narrative structure of “Company” works. Everything about this production is wholly satisfying, but it’s Mr. Rosenthal’s set that makes the pieces fit together so tightly…. Mrs. T and I dined the other night at a “gastropub” (a neologism I dislike intensely, but we seem to be stuck with it). One of the dishes that I ordered was a salad whose constituent parts included strawberries, dried apricots, goat cheese, lightly salted Marcona almonds, and a raspberry vinaigrette. As I nibbled on an almond, I found myself thinking of the salads of my childhood, which more often than not consisted of dead-tired tomatoes and iceberg lettuce slathered in

Mrs. T and I dined the other night at a “gastropub” (a neologism I dislike intensely, but we seem to be stuck with it). One of the dishes that I ordered was a salad whose constituent parts included strawberries, dried apricots, goat cheese, lightly salted Marcona almonds, and a raspberry vinaigrette. As I nibbled on an almond, I found myself thinking of the salads of my childhood, which more often than not consisted of dead-tired tomatoes and iceberg lettuce slathered in  • Smalltown, U.S.A., had two movie theaters, each of which had one screen. The Malone, the respectable one, was where I

• Smalltown, U.S.A., had two movie theaters, each of which had one screen. The Malone, the respectable one, was where I  • My mother made breakfast for our family every morning, listening to

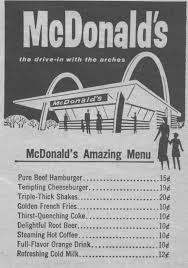

• My mother made breakfast for our family every morning, listening to  • The first McDonald’s I ever saw opened in the summer of 1968 in Cape Girardeau, a town located a half-hour north of us. The menu consisted of nine items, five of them beverages. My father sometimes took us there instead of a “real” restaurant. Far from being disappointed, my brother and I thought it a privilege.

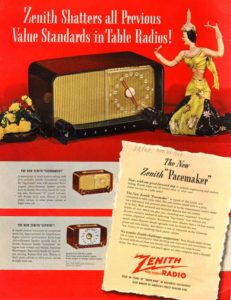

• The first McDonald’s I ever saw opened in the summer of 1968 in Cape Girardeau, a town located a half-hour north of us. The menu consisted of nine items, five of them beverages. My father sometimes took us there instead of a “real” restaurant. Far from being disappointed, my brother and I thought it a privilege. • Since the VCR was as yet a pipe dream, all TV was “appointment” TV in the Sixties. You watched shows when they aired, when they were rerun in the summer, or not at all. We did, however, have two TV sets, a Curtis Mathes cabinet model in the living room and a black-and-white portable in the kitchen (my father was a hardware salesman, so he got a deal on it). This meant I could watch a different show when I wanted to see something in which my parents weren’t interested, so long as it was on CBS or NBC. WSIL, the ABC affiliate, was in Harrisburg, Illinois, a town so far away that the residents of Smalltown could only pick it up with a rooftop antenna. The “rabbit-ear” antennas that stuck up from the back of our portable set wouldn’t do the job, no matter how much you fiddled with them.

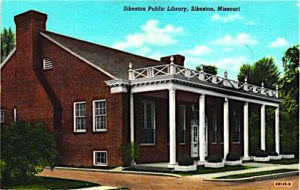

• Since the VCR was as yet a pipe dream, all TV was “appointment” TV in the Sixties. You watched shows when they aired, when they were rerun in the summer, or not at all. We did, however, have two TV sets, a Curtis Mathes cabinet model in the living room and a black-and-white portable in the kitchen (my father was a hardware salesman, so he got a deal on it). This meant I could watch a different show when I wanted to see something in which my parents weren’t interested, so long as it was on CBS or NBC. WSIL, the ABC affiliate, was in Harrisburg, Illinois, a town so far away that the residents of Smalltown could only pick it up with a rooftop antenna. The “rabbit-ear” antennas that stuck up from the back of our portable set wouldn’t do the job, no matter how much you fiddled with them. • I went every Saturday afternoon to the Smalltown Public Library, to which I started bicycling as soon as my parents thought me old enough to go by myself. It was a handsome building of modest proportions with a limited number of titles from which to pick the coming week’s leisure-time reading. But it was, along with network TV, my first window on the world beyond Smalltown, and so I reveled in every visit, invariably checking out three books—the maximum allowed—each time I went there. Sometimes I actually propped up a book on the handlebars of my bicycle and started reading it on the way home. This horrified my mother, with good reason. It’s a wonder I didn’t kill myself.

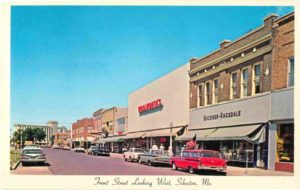

• I went every Saturday afternoon to the Smalltown Public Library, to which I started bicycling as soon as my parents thought me old enough to go by myself. It was a handsome building of modest proportions with a limited number of titles from which to pick the coming week’s leisure-time reading. But it was, along with network TV, my first window on the world beyond Smalltown, and so I reveled in every visit, invariably checking out three books—the maximum allowed—each time I went there. Sometimes I actually propped up a book on the handlebars of my bicycle and started reading it on the way home. This horrified my mother, with good reason. It’s a wonder I didn’t kill myself. • All of the clothes that I wore as a boy came from two chain stores, Sears and J.C. Penney’s, and two locally owned stores, Buckner-Ragsdale and Falkoff’s (the second of which, I rejoice to report, is still in business). Except for Levi’s and Stetson hats, clothing brands were unheard-of back then, at least in southeast Missouri. I wore what my mother bought, and did so without complaint.

• All of the clothes that I wore as a boy came from two chain stores, Sears and J.C. Penney’s, and two locally owned stores, Buckner-Ragsdale and Falkoff’s (the second of which, I rejoice to report, is still in business). Except for Levi’s and Stetson hats, clothing brands were unheard-of back then, at least in southeast Missouri. I wore what my mother bought, and did so without complaint.