No one who hasn’t written a book can know what it feels like to see it set up in type for the first time. Your own manuscript, however neatly printed it may be, simply isn’t the real thing. It’s homemade, and looks that way. You can edit it as painstakingly as you like, but you still don’t know what your words will sound like in your inner ear until you see the thing itself. It’s unnerving, half scary and half thrilling, to pull the proofs out of their package and start riffling through them, pretending to look for typos (and sometimes finding them) but mostly just gazing raptly at each page, feeling your half-forgotten sentences and paragraphs quiver to life….

Read the whole thing here.

I wrote a Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column earlier this year about how “serious” critics increasingly overvalue popular culture at the expense of high art. My central example was Elmore Leonard:

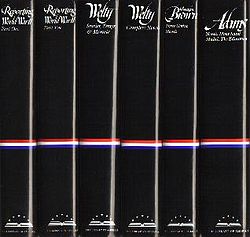

I wrote a Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column earlier this year about how “serious” critics increasingly overvalue popular culture at the expense of high art. My central example was Elmore Leonard: Allow me, if I may, to draw your attention to the mission statement that also appears on the dust jacket of Elmore Leonard: Four Novels of the 1970s: “The Library of America helps to preserve our nation’s literary heritage by publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of America’s best and most significant writing.” To that end, it has brought out “authoritative editions” of the selected works of a remarkably wide-ranging variety of American writers, among them James Baldwin, Saul Bellow, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Henry James, Sinclair Lewis, Abraham Lincoln, William Maxwell, Herman Melville, H.L. Mencken, Flannery O’Connor, Eugene O’Neill, Dawn Powell, Philip Roth, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Mark Twain, John Updike, Edith Wharton, Walt Whitman, Thornton Wilder, Tennessee Williams, Edmund Wilson, and Richard Wright.

Allow me, if I may, to draw your attention to the mission statement that also appears on the dust jacket of Elmore Leonard: Four Novels of the 1970s: “The Library of America helps to preserve our nation’s literary heritage by publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of America’s best and most significant writing.” To that end, it has brought out “authoritative editions” of the selected works of a remarkably wide-ranging variety of American writers, among them James Baldwin, Saul Bellow, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Henry James, Sinclair Lewis, Abraham Lincoln, William Maxwell, Herman Melville, H.L. Mencken, Flannery O’Connor, Eugene O’Neill, Dawn Powell, Philip Roth, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Mark Twain, John Updike, Edith Wharton, Walt Whitman, Thornton Wilder, Tennessee Williams, Edmund Wilson, and Richard Wright. What do I make of all this? I confess to not being altogether sure, though I should say at once that I am, in the main, an unabashed admirer of the Library of America and its high-minded mission. I have no doubt, however, that it keeps one eye firmly fixed on the bloody shirt of literary politics—and I also suspect that the growing “inclusiveness” of its list is also a function of the well-known fact that institutions, like bureaucracies, exist to perpetuate themselves. Once you’ve published the canon, what do you do next? The LOA, after all, isn’t a well-endowed art museum that can just sit there and do nothing. It’s a business, one whose editors, like everybody else in publishing, are intensely conscious of the bottom line. While their decision to admit Elmore Leonard to the canon may well be a pure act of practical criticism, I suspect there’s a teeny bit more to it than that.

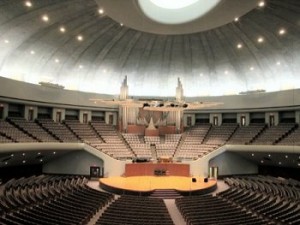

What do I make of all this? I confess to not being altogether sure, though I should say at once that I am, in the main, an unabashed admirer of the Library of America and its high-minded mission. I have no doubt, however, that it keeps one eye firmly fixed on the bloody shirt of literary politics—and I also suspect that the growing “inclusiveness” of its list is also a function of the well-known fact that institutions, like bureaucracies, exist to perpetuate themselves. Once you’ve published the canon, what do you do next? The LOA, after all, isn’t a well-endowed art museum that can just sit there and do nothing. It’s a business, one whose editors, like everybody else in publishing, are intensely conscious of the bottom line. While their decision to admit Elmore Leonard to the canon may well be a pure act of practical criticism, I suspect there’s a teeny bit more to it than that. • I performed the Berlioz Requiem with Maurice Peress and the now-defunct Kansas City Philharmonic at Independence’s 5,800-seat RLDS Auditorium in 1975. The orchestra was augmented for the occasion by a couple of dozen college students, and I was the youngest and lowliest of the lot. Accordingly, I sat in the last chair of the bass section, at once thrilled and half-petrified. Never before or since have I heard such all-enveloping sounds.

• I performed the Berlioz Requiem with Maurice Peress and the now-defunct Kansas City Philharmonic at Independence’s 5,800-seat RLDS Auditorium in 1975. The orchestra was augmented for the occasion by a couple of dozen college students, and I was the youngest and lowliest of the lot. Accordingly, I sat in the last chair of the bass section, at once thrilled and half-petrified. Never before or since have I heard such all-enveloping sounds. • My first New York City Ballet performance took place in 1987. I described this life-transforming event in the opening chapter of All in the Dances, my 2004 biography of George Balanchine. You can read what I wrote

• My first New York City Ballet performance took place in 1987. I described this life-transforming event in the opening chapter of All in the Dances, my 2004 biography of George Balanchine. You can read what I wrote  • Speaking of volcanoes, I only saw Leonard Bernstein in concert once, also at Carnegie Hall in 1988 (a very good year!). It was the forty-fifth anniversary of his debut with the New York Philharmonic, and he was conducting three of his own pieces, the Age of Anxiety Symphony, Chichester Psalms, and the Serenade after Plato’s Symposium. I was sitting in a box on the extreme right-hand side of the auditorium that was positioned in such a way as to give me a crystal-clear view of Bernstein standing in the wings, kissing the cufflinks that Serge Koussevitzky, his mentor, had given him (it was his customary pre-concert ritual) before coming out on stage.

• Speaking of volcanoes, I only saw Leonard Bernstein in concert once, also at Carnegie Hall in 1988 (a very good year!). It was the forty-fifth anniversary of his debut with the New York Philharmonic, and he was conducting three of his own pieces, the Age of Anxiety Symphony, Chichester Psalms, and the Serenade after Plato’s Symposium. I was sitting in a box on the extreme right-hand side of the auditorium that was positioned in such a way as to give me a crystal-clear view of Bernstein standing in the wings, kissing the cufflinks that Serge Koussevitzky, his mentor, had given him (it was his customary pre-concert ritual) before coming out on stage. • I once saw Bill Monroe, the inventor of bluegrass, perform at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville and met him backstage after the show. Here’s how I described the experience in a

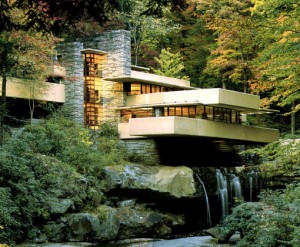

• I once saw Bill Monroe, the inventor of bluegrass, perform at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville and met him backstage after the show. Here’s how I described the experience in a  • I paid my first visit to Fallingwater in 2003 (and blogged about it

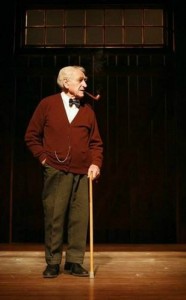

• I paid my first visit to Fallingwater in 2003 (and blogged about it  • I also saw the eighty-six-year-old James Whitmore play the role of the Stage Manager in Our Town in Peterborough, New Hampshire, the town where Thornton Wilder’s play was written and which it is thought to depict. Mrs. T and I visited Willa Cather’s grave that same afternoon and went to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery the next day, an experience about which I blogged

• I also saw the eighty-six-year-old James Whitmore play the role of the Stage Manager in Our Town in Peterborough, New Hampshire, the town where Thornton Wilder’s play was written and which it is thought to depict. Mrs. T and I visited Willa Cather’s grave that same afternoon and went to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery the next day, an experience about which I blogged