“The ironist is not bitter, he does not seek to undercut everything that seems worthy or serious, he scorns the cheap scoring-off of the wisecracker. He stands, so to speak, somewhat at one side, observes and speaks with a moderation which is occasionally embellished with a flash of controlled exaggeration. He speaks from a certain depth, and thus he is not of the same nature as the wit, who so often speaks from the tongue and no deeper. The wit’s desire is to be funny; the ironist is only funny as a secondary achievement.”

“The ironist is not bitter, he does not seek to undercut everything that seems worthy or serious, he scorns the cheap scoring-off of the wisecracker. He stands, so to speak, somewhat at one side, observes and speaks with a moderation which is occasionally embellished with a flash of controlled exaggeration. He speaks from a certain depth, and thus he is not of the same nature as the wit, who so often speaks from the tongue and no deeper. The wit’s desire is to be funny; the ironist is only funny as a secondary achievement.”

Robertson Davies, The Cunnng Man

Kaufman and Hart invented or perfected many of the now-formulaic devices that power TV sitcoms, and one of them, the crazy family with a single sane member, is displayed to well-tooled effect in the saga of the Vanderhofs, whose contentedly haphazard daily lives are concisely summed up in the first paragraph of the stage directions: “This is a house where you do as you like, and no questions asked.” No less seductive, though, is the fantasy that they collectively embody: Not only do they follow their bliss to the uttermost limits of absurdity, but the rent gets paid and the pantry filled without their having to hold down nine-to-five jobs…

Kaufman and Hart invented or perfected many of the now-formulaic devices that power TV sitcoms, and one of them, the crazy family with a single sane member, is displayed to well-tooled effect in the saga of the Vanderhofs, whose contentedly haphazard daily lives are concisely summed up in the first paragraph of the stage directions: “This is a house where you do as you like, and no questions asked.” No less seductive, though, is the fantasy that they collectively embody: Not only do they follow their bliss to the uttermost limits of absurdity, but the rent gets paid and the pantry filled without their having to hold down nine-to-five jobs…

As for me, I wasn’t nervous, just excited, perhaps because I didn’t have all that much to do. Whatever the reason, I read my lines as efficiently and effectively as I could, and the rest of the time I just sat there and goggled, both at the rehearsal and at the performance. I’m not sure I was supposed to laugh in front of the audience, but I couldn’t help myself. I told J. (that’s what she’s called) that performing with her felt like taking a ride in a self-driving car that did all the work for me, which made her giggle.

As for me, I wasn’t nervous, just excited, perhaps because I didn’t have all that much to do. Whatever the reason, I read my lines as efficiently and effectively as I could, and the rest of the time I just sat there and goggled, both at the rehearsal and at the performance. I’m not sure I was supposed to laugh in front of the audience, but I couldn’t help myself. I told J. (that’s what she’s called) that performing with her felt like taking a ride in a self-driving car that did all the work for me, which made her giggle.

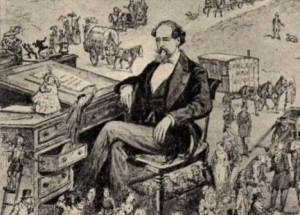

• A cyberfriend writes to remind me that when Charles Dickens visited America for the first time in 1842, he was mobbed wherever he went, an experience that he described in a letter to John Forster, his friend and biographer:

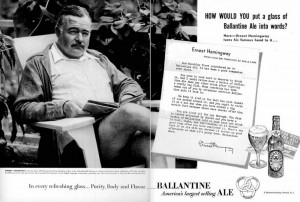

• A cyberfriend writes to remind me that when Charles Dickens visited America for the first time in 1842, he was mobbed wherever he went, an experience that he described in a letter to John Forster, his friend and biographer: I suppose a modern-day reader might regard this as a nice problem to have, but what strikes me most forcibly about Dickens’ dilemma (if you want to call it that) is that it was a novelist who was having it. Today it’s unimaginable that any writer would be treated that way, whether in America or elsewhere. Our “rock stars” are…well, rock stars. Or, more likely, movie and TV stars. We simply don’t confer mass celebrity on writers nowadays. If I had to guess, I’d say that Ernest Hemingway was the last novelist of consequence whom a considerable number of Americans would have been at all likely to know by sight—he was, in fact, famous enough to be paid to endorse products—and he died more than a half-century ago.

I suppose a modern-day reader might regard this as a nice problem to have, but what strikes me most forcibly about Dickens’ dilemma (if you want to call it that) is that it was a novelist who was having it. Today it’s unimaginable that any writer would be treated that way, whether in America or elsewhere. Our “rock stars” are…well, rock stars. Or, more likely, movie and TV stars. We simply don’t confer mass celebrity on writers nowadays. If I had to guess, I’d say that Ernest Hemingway was the last novelist of consequence whom a considerable number of Americans would have been at all likely to know by sight—he was, in fact, famous enough to be paid to endorse products—and he died more than a half-century ago.