“As you begin to get older you begin to realize the trick time is playing, and that unless you do something about it, the passage of time is nothing but the encroachment of the horrible banality of the past on the pure future.”

“As you begin to get older you begin to realize the trick time is playing, and that unless you do something about it, the passage of time is nothing but the encroachment of the horrible banality of the past on the pure future.”

Walker Percy, Lancelot (courtesy of D.G. Myers)

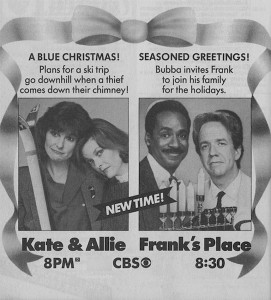

Twenty-seven years ago next month, a black-themed half-hour comedy series called

Twenty-seven years ago next month, a black-themed half-hour comedy series called  Not surprisingly, Reid understood full well what he’d gotten himself into. “Hugh, I think this is brilliant, but it scares hell out of me,” he said to Hugh Wilson, the show’s creator. “I’ve never seen this on television. I’m not sure television is ready for this.” Nor was it: Frank’s Place was cancelled after a single twenty-two-episode season, and today it is known only to TV historians and aging fans.

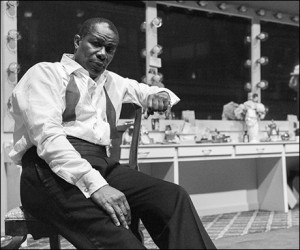

Not surprisingly, Reid understood full well what he’d gotten himself into. “Hugh, I think this is brilliant, but it scares hell out of me,” he said to Hugh Wilson, the show’s creator. “I’ve never seen this on television. I’m not sure television is ready for this.” Nor was it: Frank’s Place was cancelled after a single twenty-two-episode season, and today it is known only to TV historians and aging fans. Needless to say, I had no earthly idea back in 1987 that I would someday write full-length biographies of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington that dealt with intraracial prejudice, much less a one-man play about Armstrong and Joe Glaser, his Jewish manager. Still, I rather doubt that I would have written the following speech from Satchmo at the Waldorf in quite the same way had I not seen “Frank Joins the Club”:

Needless to say, I had no earthly idea back in 1987 that I would someday write full-length biographies of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington that dealt with intraracial prejudice, much less a one-man play about Armstrong and Joe Glaser, his Jewish manager. Still, I rather doubt that I would have written the following speech from Satchmo at the Waldorf in quite the same way had I not seen “Frank Joins the Club”:

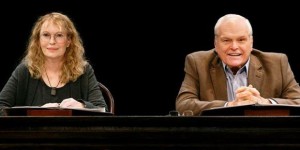

One reason why “Love Letters” is so frequently produced is that it’s written in such a way as to facilitate both come-and-go celebrity casting and bargain-basement staging. Not only is there no set, but the actors sit together at a table and read from scripts instead of memorizing their lines. But the enduring success of “Love Letters” is far more than a mere matter of logistical convenience. It’s one of Mr. Gurney’s best plays, a tender study of thwarted love….

One reason why “Love Letters” is so frequently produced is that it’s written in such a way as to facilitate both come-and-go celebrity casting and bargain-basement staging. Not only is there no set, but the actors sit together at a table and read from scripts instead of memorizing their lines. But the enduring success of “Love Letters” is far more than a mere matter of logistical convenience. It’s one of Mr. Gurney’s best plays, a tender study of thwarted love…. •

•  In 2001 I wrote a review of the

In 2001 I wrote a review of the  Thora Birch, a raven-haired nineteen-year-old who plays Enid with a heartbreaking combination of cynicism and fragility, also appeared in American Beauty (1999). Ghost World may seem at first glance to echo that smug film’s unearned contempt for suburban life. But American Beauty offered easy answers to loaded questions (that’s why it won so many Oscars—Hollywood gives prizes only to movies that tell us what it wants to hear), whereas Ghost World is a movie without any answers at all. That is the source of its pathos. Like every teenager, Enid longs to be shown how to live, but the ghostly adults who drift in and out of her unhappy life offer her no counsel. Instead, she has been set adrift on the sea of relativity, looking for a safe harbor on an uncharted coast.

Thora Birch, a raven-haired nineteen-year-old who plays Enid with a heartbreaking combination of cynicism and fragility, also appeared in American Beauty (1999). Ghost World may seem at first glance to echo that smug film’s unearned contempt for suburban life. But American Beauty offered easy answers to loaded questions (that’s why it won so many Oscars—Hollywood gives prizes only to movies that tell us what it wants to hear), whereas Ghost World is a movie without any answers at all. That is the source of its pathos. Like every teenager, Enid longs to be shown how to live, but the ghostly adults who drift in and out of her unhappy life offer her no counsel. Instead, she has been set adrift on the sea of relativity, looking for a safe harbor on an uncharted coast.