Mrs. T and I are in the process of driving down California’s Highway 1 from San Francisco to San Diego, seeing shows along the way. Yesterday we stopped at Ragged Point Inn, which is south of Big Sur and not far from the Hearst Castle, to give me time to write and file a piece for The Wall Street Journal. I doubt there’s a more beautiful drive in America, or a more beautiful spot than Ragged Point.

Mrs. T and I are in the process of driving down California’s Highway 1 from San Francisco to San Diego, seeing shows along the way. Yesterday we stopped at Ragged Point Inn, which is south of Big Sur and not far from the Hearst Castle, to give me time to write and file a piece for The Wall Street Journal. I doubt there’s a more beautiful drive in America, or a more beautiful spot than Ragged Point.

Would that I could spend all my time here gazing at the sea, but as James Bond says to Vesper Lynd in Casino Royale, “If it wasn’t for the job, we wouldn’t be here,” and I’ve never been one to shirk my journalistic duty, so I’ll be spending a chunk of today writing about Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau for Friday’s “Sightings” column.

Tomorrow we resume our travels, about which more in due course. Until then, we’re more or less incommunicado–our cell phones don’t work up here and the wi-fi at the inn is agonizingly slow–so if you want anything, get back to us on Tuesday night.

In the meantime, I hope that wherever you are is at least a quarter as pretty as where we are.

I rejoice to report that

I rejoice to report that  What, then, are we to make of Fischer-Dieskau today? My own experience is, I think, worth recounting in this connection. Like so many music lovers of my generation (I was born in 1956), it was through his recordings that I discovered the beauties of German Lieder, and for a long time I thought there was no other way to sing them. Not until later did I become acquainted with the work of such singers of the 78 era as Tauber, Karl Erb, Hans Hotter, Gerhard Hüsch, Herbert Janssen, Alexander Kipnis, Lotte Lehmann, John McCormack, Charles Panzéra, Heinrich Schlusnus, Aksel Schiøtz and Elisabeth Schumann, all of whom exemplified in their differing ways the older tradition so eloquently epitomized by Samuel Lipman: “The best of the older performances give an impression of simplicity combined with grandeur, of sensitivity to each poem’s mood combined with a clear, unforced and restrained projection of the individual words.”

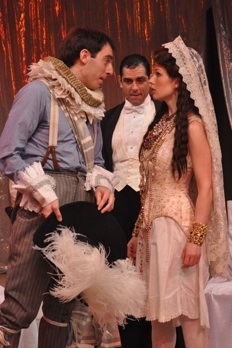

What, then, are we to make of Fischer-Dieskau today? My own experience is, I think, worth recounting in this connection. Like so many music lovers of my generation (I was born in 1956), it was through his recordings that I discovered the beauties of German Lieder, and for a long time I thought there was no other way to sing them. Not until later did I become acquainted with the work of such singers of the 78 era as Tauber, Karl Erb, Hans Hotter, Gerhard Hüsch, Herbert Janssen, Alexander Kipnis, Lotte Lehmann, John McCormack, Charles Panzéra, Heinrich Schlusnus, Aksel Schiøtz and Elisabeth Schumann, all of whom exemplified in their differing ways the older tradition so eloquently epitomized by Samuel Lipman: “The best of the older performances give an impression of simplicity combined with grandeur, of sensitivity to each poem’s mood combined with a clear, unforced and restrained projection of the individual words.” The answer may depend in part on how familiar you are with “Man and Superman.” If you’ve never seen or read it, you probably won’t suspect that you’re seeing a version that’s been cut so heavily, and you’ll definitely come away with a clear sense of what Shaw was trying to do. Just as important, you’ll also have a whale of a good time. This production, adapted and directed by David Staller, emphasizes the comic side of “Man and Superman” while managing to do justice to the play’s philosophical aspect, and it has all the fizz of a case of Veuve Clicquot….

The answer may depend in part on how familiar you are with “Man and Superman.” If you’ve never seen or read it, you probably won’t suspect that you’re seeing a version that’s been cut so heavily, and you’ll definitely come away with a clear sense of what Shaw was trying to do. Just as important, you’ll also have a whale of a good time. This production, adapted and directed by David Staller, emphasizes the comic side of “Man and Superman” while managing to do justice to the play’s philosophical aspect, and it has all the fizz of a case of Veuve Clicquot….