How come nobody told me about these?

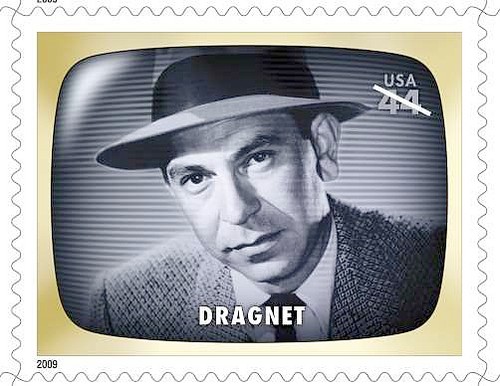

If you’ve never seen any of the original black-and-white Dragnet episodes from the Fifties–most of which, alas, have been out of circulation for decades–you don’t know what the show was really like. As I wrote in an essay called “In Praise of Drabness” that was published last year in National Review:

Like the later color version, the Dragnet of the Fifties was a no-nonsense half-hour police procedural that sought to show how ordinary cops catch ordinary crooks. The scripts, many of which were written by James E. Moser, combined straightforwardly linear plotting (“It was Wednesday, October 6. It was sultry in Los Angeles. We were working the day watch out of homicide”) with clipped dialogue spoken in a near-monotone, all accompanied by the taut, dissonant music of Walter Schumann. Then and later, most of the shots were screen-filling talking-head closeups, a plain-Jane style of cinematography that to this day is identified with Jack Webb.

The difference was that in the Fifties, Joe Friday and Frank Smith, his chubby, mildly eccentric partner, stalked their prey in a monochromatically drab Los Angeles that seemed to consist only of shabby storefronts and bleak-looking rooms in dollar-a-night hotels. Nobody was pretty in Dragnet, and almost nobody was happy. The atmosphere was that of film noir minus the kinks–the same stark visual grammar, only cleansed of the sour tang of corruption in high places. But even without the Chandleresque pessimism that gave film noir its seedy savor, Dragnet was still rough stuff, more uncompromising than anything that had hitherto been seen on TV. In 1954 Time called the series “a sort of peephole into a grim new world. The bums, priests, con men, whining housewives, burglars, waitresses, children, and bewildered ordinary citizens who people Dragnet seem as sorrowfully genuine as old pistols in a hockshop window.”

Here’s the opening sequence of “The Big Cast,” a 1952 Dragnet featuring Lee Marvin. It’ll give you a feel for what you’ve been missing:

Nowadays, of course, most people know “Amadeus” from Mr. Forman’s film, an opulently designed costume piece that is great fun to watch but lacks the expressionistic intensity of the original play. In the stage version, by contrast, the spotlight never moves away from Salieri, an ambitious but modestly talented composer who is driven to the brink of madness by the inexplicable fact that supreme genius and juvenile vulgarity exist side by side in Mozart, his hated competitor: “It seemed to me that I had heard the voice of God–and that it issued from a creature whose own voice I had also heard–and that it was the voice of an obscene child!”

Nowadays, of course, most people know “Amadeus” from Mr. Forman’s film, an opulently designed costume piece that is great fun to watch but lacks the expressionistic intensity of the original play. In the stage version, by contrast, the spotlight never moves away from Salieri, an ambitious but modestly talented composer who is driven to the brink of madness by the inexplicable fact that supreme genius and juvenile vulgarity exist side by side in Mozart, his hated competitor: “It seemed to me that I had heard the voice of God–and that it issued from a creature whose own voice I had also heard–and that it was the voice of an obscene child!” Erich Kunzel, the conductor of the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, conducted his last concert on August 1, exactly a month before he died. This event put me in mind of the surprisingly small number of performances that have been given and masterpieces that have been created by artists who knew they were dying, and–not so surprisingly–a “Sightings” column came out of my reflections on this grim subject.

Erich Kunzel, the conductor of the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, conducted his last concert on August 1, exactly a month before he died. This event put me in mind of the surprisingly small number of performances that have been given and masterpieces that have been created by artists who knew they were dying, and–not so surprisingly–a “Sightings” column came out of my reflections on this grim subject.